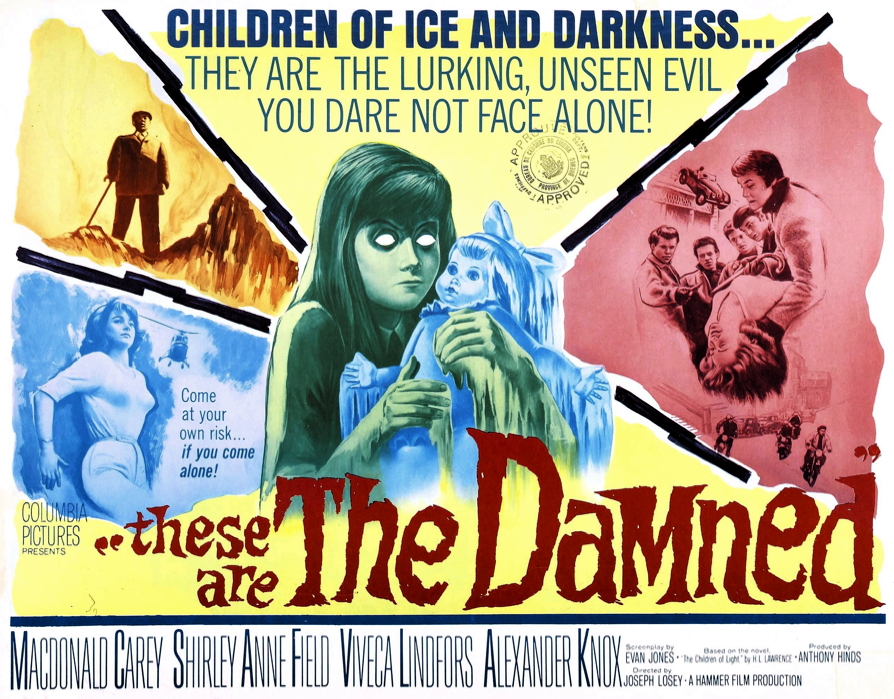

I was originally going to post about The Damned (aka These are the Damned, 1963) as a “double feature” with X the Unknown (1956), which is also a Hammer black-and-white SF film dominated by Geiger counter clicks. The Damned can make your skin crawl with very little effort, especially if you’ve just watched something like the recent HBO miniseries Chernobyl or earlier portrayals of nuclear horror like Threads (1984) or The Day After (1983). But the Hammer films are working purely in the realm of science fiction, not realism, and are much more palatable in a genre package. In this case, the source of deadly radiation is not a creature bubbling up from inner Earth, as in X the Unknown, but nine 11-year-old children born in a nuclear accident, a government experiment gone awry. These children are cold to the touch and highly radioactive, but they can thrive if kept in isolation. So the government locks them in an underground classroom, teaching them through closed-circuit television and assuring that Big Brother knows best. These, the Damned of the title, are the government’s master race for a post-holocaust world. When we’re all dead, the children will survive amidst the nuclear fallout. It’s not a matter of if the world meets this fate, but when. The queasy tension arrives when our main characters stumble across the children and try to help them, not knowing what they are and how they’re advancing closer to death with every second spent in their presence. “Don’t you understand?” gasps Oliver Reed to one of the innocents late in the film. “You’re poison.” They can’t be rescued from their comfortable prison – much as the human race can’t be saved. Or so this film argues – a key work of early 60’s paranoia for the Bomb. We’re all damned.

Oliver Reed as King, the sociopath leader of a gang of teddy boys.

One of the brilliant aspects of the film is that you wouldn’t know that was the plot until over a half hour has elapsed. You wouldn’t even know this was a film of the fantastic. Director Joseph Losey, the blacklisted American who was reportedly pushed out of directing X the Unknown because of the McCarthyite lead, Dean Jagger, opens his film as a juvenile delinquent drama. Emerging star Reed plays King, the leader of a rough group of “teddy boys” who use King’s attractive sister, Joan (Shirley Anne Field, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning), to lure and rob the American retiree Simon (Macdonald Carey, Shadow of a Doubt). Out of guilt – though it’s sketchily drawn – Joan returns to Simon and escapes with him on his boat, King and his gang in pursuit. King, it’s clear, has an unhealthy attachment to his sister, played by Reed as a sublimated incestuous longing, a sensationalist portrait of sexual repression and rage that would make him a natural for later Ken Russell roles. Simon seduces Joan, which is uncomfortable not just because of the significant age difference but his aggressive advances on the young woman. Carey plays his character entirely without charm, but soon this matters less than you might think, as Simon and Joan, in fleeing from King and his gang, accidentally stumble into the government’s secret experiments with a new race that can thrive in a radioactive world. If that sounds like a whiplash plot twist, it’s somehow…not quite. Losey begins to introduce us to his Plot B before Simon, Joan, and King have wandered into it, and when they do cross the threshold, they share our curiosity and concern. All the stakes introduced in the beginning of the film are subsumed by much greater issues. The three interlopers must now contend with the same unsolvable endgame scenarios in which the government has already been entangled. The story is adapted from a 1960 novel, The Children of Light, by H.L. Lawrence.

King, Joan (Shirley Anne Field), and Simon (Macdonald Carey) plot to help the subjects of a secret government experiment.

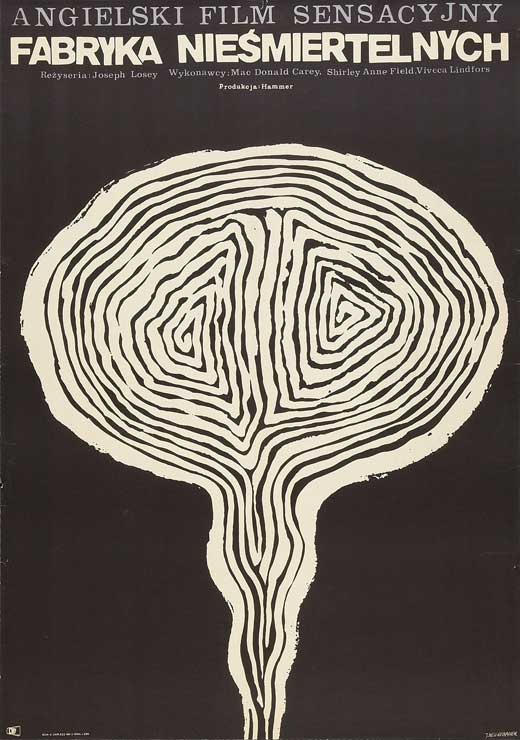

An excellent supporting cast includes Swedish actress Viveca Lindfors (Dark City) as a cynical sculptor and Alexander Knox (The Vikings) as the man who’s been keeping the details of his government work a secret from her. Knox, like Losey, had been blacklisted by the HUAC. Losey commits fully to the very bleak ending which, despite its pessimism, is an exhilarating piece of filmmaking. Following the story to its natural conclusion and refusing to force a happy ending, Losey strips away the Rod Serling-esque preachy monologues that briefly threaten to dominate the finale, leaving the film almost dialogue-free as it follows each of its characters to their ultimate fate. The ending may be the most devastating in the Hammer canon – which is no mild compliment, since Hammer was perfectly capable of producing intelligent, meaningful, powerful films when they were inclined (such as Yesterday’s Enemy or Never Take Sweets from a Stranger). Even so, the film was marketed as exploitation product: in the UK, as a youth in revolt drama; in the US, as an off-brand Village of the Damned sequel. Indicator packs their region-free Blu-ray with supplements, including critical analyses and cast interviews; it’s part of Hammer Vol. 4: Faces of Fear, the box set that also includes The Revenge of Frankenstein, The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll, and Taste of Fear. Indicator’s fifth volume of Hammer films (Death & Deceit) is scheduled for release at the end of this month, and will include the thriller and adventure films Visa to Canton (1961), The Pirates of Blood River (1962), The Scarlet Blade (1963), and The Brigand of Kandahar (1965).