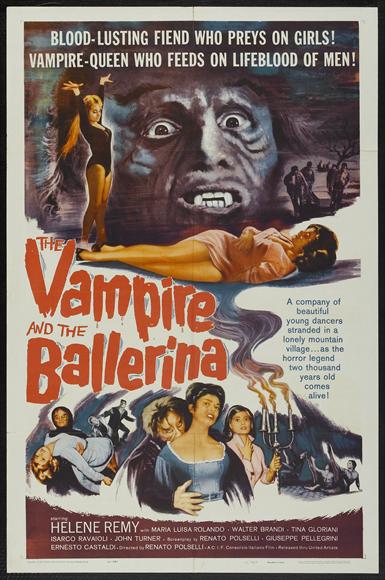

Renato Polselli’s L’amante del vampiro (The Vampire’s Lover, 1960) – released two years late in the U.S. as The Vampire and the Ballerina, on a double-bill with Vincent Price’s Tower of London – represents Italy’s newfound embrace of Gothic horror, which would flourish by the mid-60’s. I vampiri, directed by Ricardo Freda and reportedly completed by his cinematographer Mario Bava, opened the gates to this style of Italian filmmaking upon its release in 1957, and Bava himself was soon to map this territory thoroughly, beginning with La maschera del demonio (aka Black Sunday, 1960). Polselli’s film, which I’ll call The Vampire and the Ballerina since that’s the title of the Shout Factory 2018 Blu-ray release, confidently embraces the iconography of both the Tod Browning Dracula and, in particular, the more recent Terence Fisher for Hammer. Yet this isn’t a period piece. The characters are young dance students (foreshadowing Suspiria) who are preyed upon by the vampire living in the seemingly abandoned castle in the neighboring woods. Polselli foregrounds the sex, with overflowing cleavage, flimsy negligees, and a barely-subtext theme of vampirism as a carnal, sadomasochistic hunger, and only departs from the Dracula model by making his monster a prune-faced, shaggy-haired, lumpy-fleshed creature that looks like it might have crawled out of a radioactive pond.

Dance practice.

Despite the broad cast of students, the story quickly narrows its focus to just three girls. First there’s Brigida (Bava Sanni), seen in the opening sequence fetching water from a roaring waterfall before being stalked by a shadowy, cloaked figure. She returns with a neck bite, over which a Van Helsing-like professor (Ugo Cragnani) and a skeptical doctor (Giorgio Braccesi) argue: vampire, or merely the scrape of some thorns? Then there’s Luisa (Hélène Remy), the vivacious lover of mustachioed, barrel-chested dance teacher Giorgio (Gino Turini, billed as John Turner). Finally, we get to know Francesca (Tina Gloriani), Luisa’s friend, who frets that her boyfriend, the professor’s grandson Luca (Isarco Ravaioli), might have a wandering eye. During a picnic, the girls frolic by the waterfall before Luisa and Francesca spy a funeral procession. It’s actually for Brigida, and in a marvelous scene, likely inspired by Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Vampyr (1932), we see through the glass window of the coffin the occupant’s eyes open and look about in panic. The camera takes her POV as she passes beneath the cemetery gates and between the tall cypress trees before being lowered into the ground, the flung dirt covering the glass. All of this is impressively dream-like, which might be a more polite way of saying that there is no reasonable explanation for why her friends would be ignorant of her funeral, or why none of the casket bearers happens to notice that the woman they’re carrying isn’t dead. The style and effective sense of a waking nightmare is all that matters. As night falls, Luisa, Francesca, and Luca take shelter in that castle, and are soon surprised that it isn’t abandoned at all.

Luisa (Hélène Rémy) explores the vampire’s castle.

This Gothic abode is actually the home to the Contessa Alda (Maria Luisa Rolando), with a Corman-esque portrait hanging on the wall depicting her likeness from centuries earlier. When questioned why she is wearing the same vintage clothing from the portrait, Alda says, “I don’t care for the world you live in. It’s not my world…I don’t approve of it.” Very soon after arriving, a wandering Luisa is waylaid by the vampire, whose bite sends her into ecstasy. Returning to her companions shaken, they decide to quickly leave the castle which they’ve described as a “labyrinth,” but not before Alda whispers to Luca that he should pay her a visit after his girlfriend’s gone to bed. He strokes her hand and promises he will. This relationship comes out of nowhere, but equally surprising is the vampire’s subsequent graveyard visit to Brigida, whom he stakes right after promising her Alda’s castle. “I am now and forever will be master of my world!” he declares, echoing Alda’s earlier demarcation of different “worlds” – that of the living and that of the dead, the latter wrapped cozily in the cobwebbed past. Soon enough, following a failed assignation between Luca and Alda, we learn more of the relationship between the two castle-dwellers. According to Alda, he pretends to be her servant while actually dominating her entirely; and she submits to his depraved games, allowing him to drink her blood to regain, however briefly, his youthful appearance. (Though he also taunts her with “Only I can preserve your youth!”) Almost as startling as this back-and-forth, blood-swapping S&M coupling is the revelation of the vampire’s true name: Herman. Alas that the words “Count Herman” never cross anyone’s lips.

Brigida (Bava Sanni) is betrayed by the vampire who made her.

Luisa’s Lucy Westenra-like transition to the dark side is revealed in a scene lifted directly from Hammer’s Dracula, as she prepares her neck for biting as Herman manifests at her window. Polselli, however, pushes the sexualized nature of the encounter to such a degree that it may no longer be metaphor: with a lingering close-up of his clawed hand becoming that of a young man’s once again, the fingers digging into the linen, it’s implied that’s what’s just off camera is a bit more than a bite. Events lead inevitably toward a castle confrontation between vampires and their would-be slayers, all told with Polselli’s strangely collage-like assemblage of ideas and iconography, which, again, could be generously called dream-like. A writhing vampire victim chained to a dungeon wall anticipates Jean Rollin’s Requiem for a Vampire (1972). Francesca explores and is pursued within the castle’s labyrinth of corridors before a door swings shut behind her. Vampire hunters Luca and Giorgio use candlesticks to form crosses as protection. A confrontation above the castle, as the sun rises, is the most interesting, exposing the vampires’ fraught relationship as they double-cross, plead, rapidly age and then disintegrate, Christopher Lee-style, into piles of dust. But what lingers in the mind is the film’s saucy, censor-flaunting sensuality, from Contessa Alda’s center-frame naked legs as she lures Luca to her bed, to the woodland dance institute’s impromptu erotic dances. The showstopper of the latter begins with Giorgio playing a piano melody on the theme of “vampire,” which eventually incorporates what sounds like theremin while the young women writhe before the fireplace, and finally transitions into a swinging big band jazz number. When the professor explains the allure of the vampire, this fetching bunch hang on his every word, before one concludes that a vampire is “like a Prince Charming, then.” They’re eager to be bitten.