In one thousand Gandahar was destroyed and all its people killed.

One thousand years ago Gandahar will be saved and all the inevitable avoided.

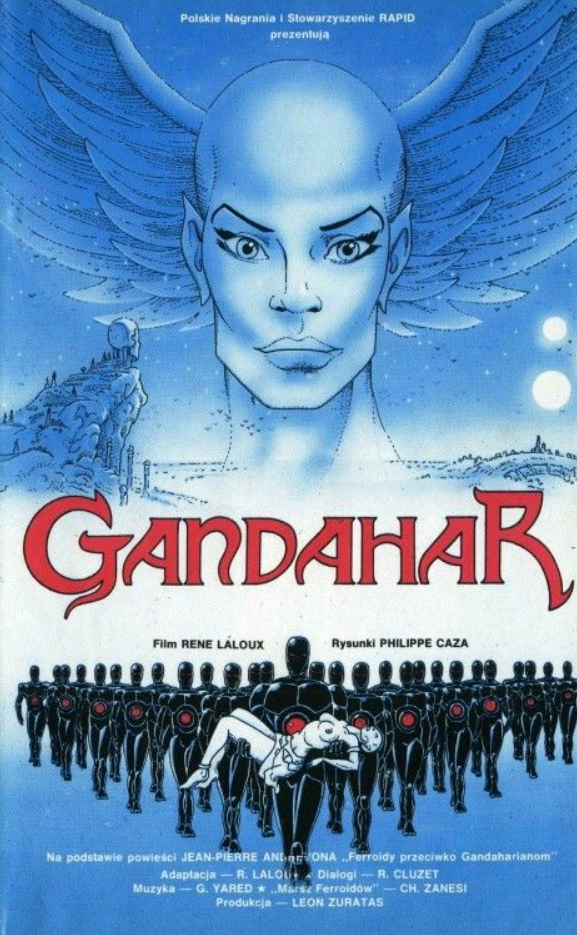

Gandahar (1987), released in the U.S. as the maimed Light Years, is the third and final feature length film by French animator René Laloux, of Fantastic Planet fame. Its origins reach back a decade before, when Laloux desired to adapt a novel by Jean-Pierre Andrevon, Les Hommes-machines contre Gandahar (The Machine-Men vs. Gandahar), in much the way Fantastic Planet was an adaptation of another high-concept SF novel (Oms en série by Stefan Wul). At the time, Laloux was also ambitiously attempting to launch a 10-part animated TV series to be called Les Pièges du futur (The Pitfalls of the Future), which was cut down into just one part, expanded to become a feature: Time Masters (Les Maîtres du temps, 1982), made with the legendary artist Moebius (Jean Giraud) and a crew of Hungarian animators. Gandahar was going to be a similar collaboration with a different artist as chief designer – Philippe Caza, the psychedelic draftsman who was also a veteran of Metal Hurlant, the landmark French comic magazine. But Gandahar failed to secure financing, and with focus shifting to Time Masters, it was not until years later that production could begin with the assistance of a Korean animation studio. The result is more polished, consistent, and complete-feeling than Time Masters (no major slight to that film, which is among my favorite animated features), acting as a fitting bookend to a Laloux SF trilogy.

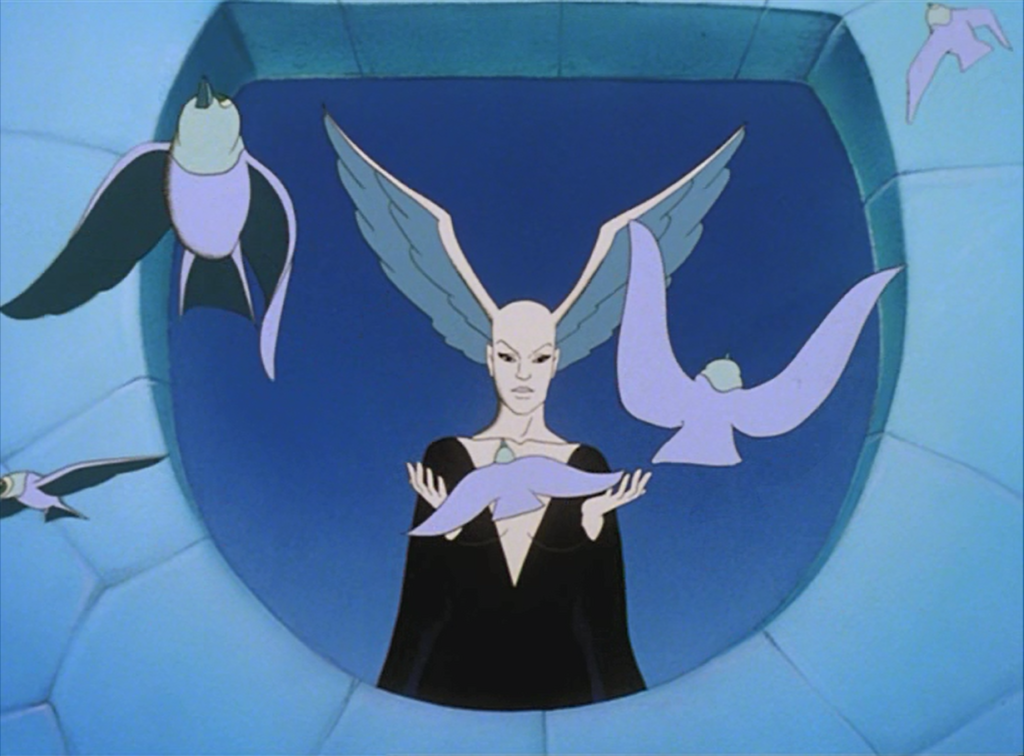

Ambisextra, who governs the land of Jasper on the planet Gandahar.

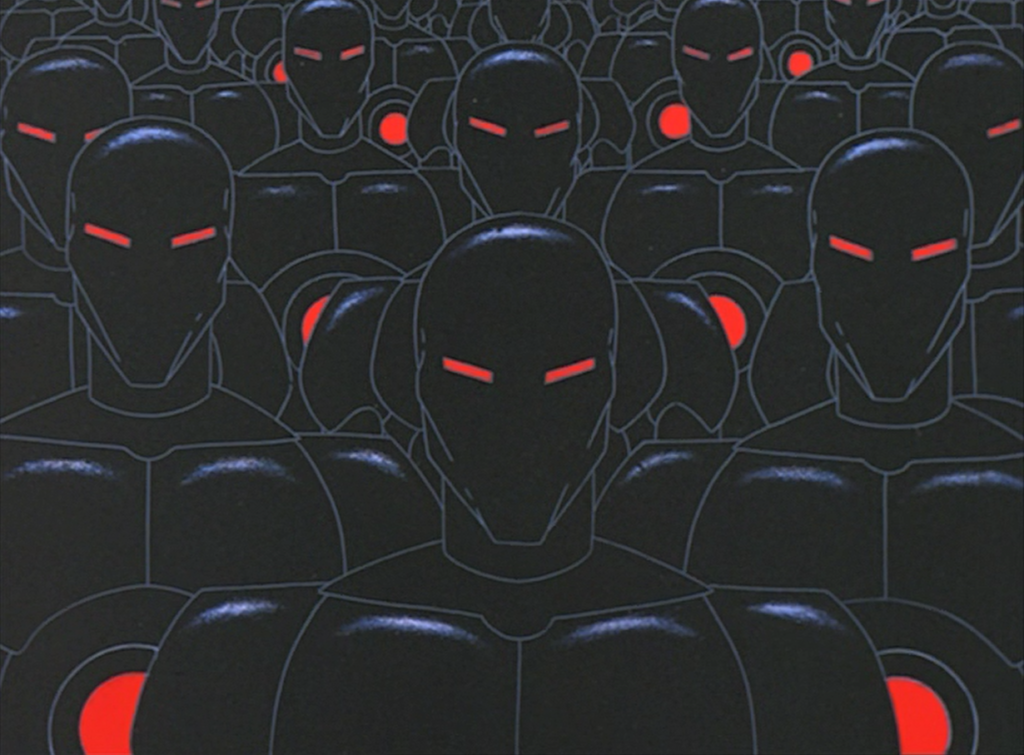

The sophisticated plot takes a backseat to Laloux’s continued obsession with alien flora and fauna – where the fauna is often also flora. An extended opening prologue evokes Fantastic Planet with its narrative-free observations of the strange creatures on Gandahar, making it clear to us that there are no strong boundaries to divide humanoid, plant, and beast. Animals are born budding out of the soil, and a green-skinned woman breastfeeds a long-snouted creature. Even some of the architecture resembles living things, like a home that looks like it once was a giant tortoise, and, most central to the film, a palace which is carved to resemble a giant nude woman, whose head detaches to become an escaping ark in times of crisis. But as the story progresses, another conceit moves closer to the spotlight, that part of this continuum includes machines. “Mirror birds” used by Ambisextra, who leads the Council that rules the land of Jasper, are living cameras that can broadcast footage back to the palace. A flying manta ray used by the hero Sylvain has skin that looks like metal plates bolted together, an airplane-creature. Yet the threat encroaching upon Gandahar is an army of Metal Men, covered in black armor and with glowing red eyes, firing lasers from their fingers which turn the planet’s inhabitants into statues, like the Blue Meanies invading Pepperland in Yellow Submarine (1968). The Metal Men are led by one they call the Great Procreator, and they despise the “civilization of wasteful pleasure.” Placing the petrified natives into eggs, they deliver them to a glowing door, out of which they emerge as more metal soldiers. Sylvain is dispatched to untangle this mystery, joining up with a woman named Airelle, and eventually discovering a giant living brain floating in the Circumscribing Ocean: the Metamorphis, which claims no sinister intent. Back home, the Council reveals they created Metamorphis as an experiment, but it seems to have evolved into something more powerful. Deepening the mystery are the Transformed, mutants exiled to the underground who once had the gift of foresight, now stripped down to just a handed-down prophecy, quoted at the top of this article. They speak in past and present tense at once: “He was/will be from Gandahar.”

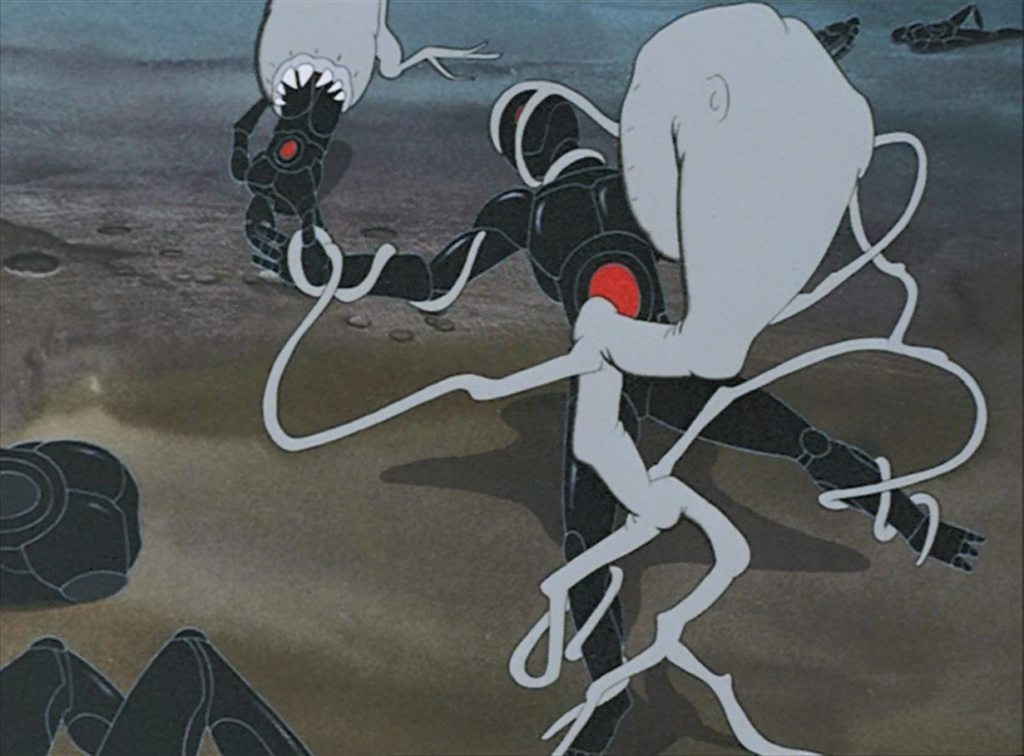

Living weapons used by the natives of Jasper attack the Metal Men.

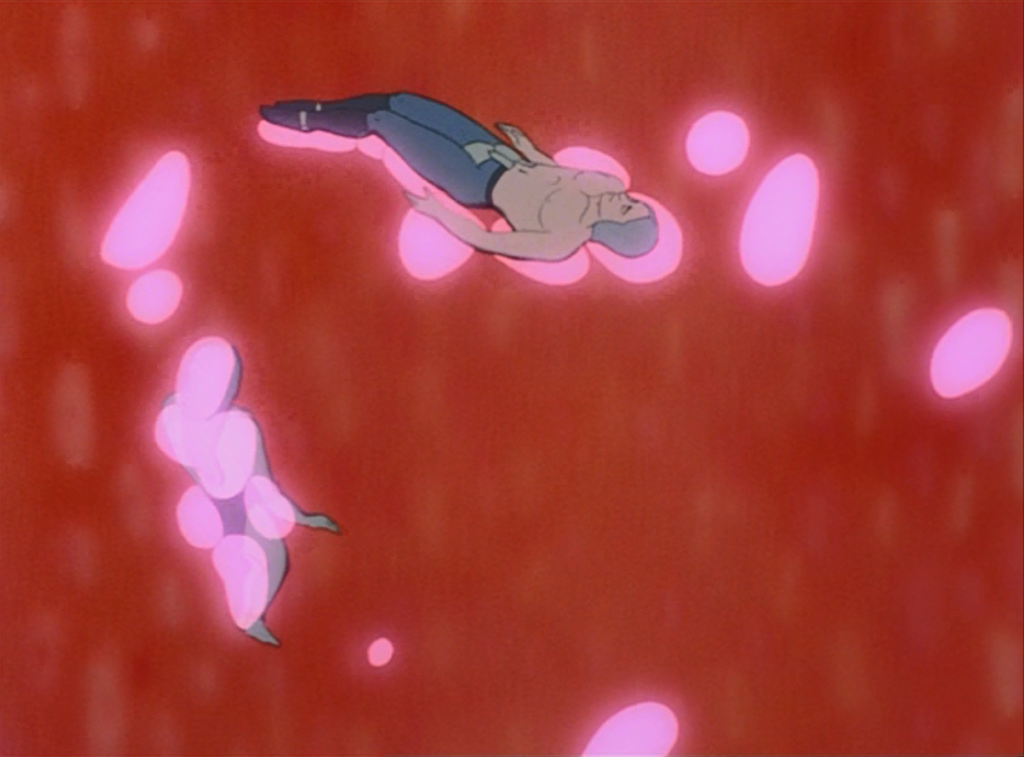

The story is guided by a gentle and appropriately alien score by Gabriel Yared (The Talented Mr. Ripley, The English Patient), which follows in the footsteps of Fantastic Planet, expressing curiosity and wonder for the lifeforms of the world, and militaristic, electronic chants for the armies of Metal Men. The visuals invoke the colored-pencil look of Fantastic Planet, as though you’re seeing pages from a graphic novel come to life, though here the animation is notably more sophisticated: when Sylvain and Airelle are absorbed into the Metamorphis, they become cells traveling through blood vessels; when Sylvain uses his gun, it fires seeds which sprout fast-growing thorn bushes that puncture his enemies; the Gandahar soldiers ride dragonflies and drop bombs that turn into pale vine creatures with sharp teeth, holding the Metal Men tight before swallowing them whole. When Sylvain and the Transformed travel one thousand years into the future, they walk across a Gandaharian landscape like the cover of an 80’s heavy metal album, the surface of the planet covered in a black metal sheen, all organic things destroyed, asteroid-like rocks twisting overhead like debris flung up after the planet had been remade. The world of the natural, on the other hand, has lightly erotic overtones, with abundant nudity and some of the natural objects resembling certain sexual organs – though never in any explicitly obvious or unintentionally humorous way. This is one of the most successful aspects of Gandahar, the way the film expresses its vision of all of nature being connected, and the obscene way it wars with itself without justification: here, the machines are just as organic as the creatures they enslave – they’ve just forgotten.

Sylvain and Airelle travel through the Metamorphis.

Gandahar was released in 1988 as Light Years after Harvey Weinstein purchased the film, cut it down (removing one of the film’s more erotic moments), hired Isaac Asimov to write dialogue for prestige value, and enlisted an all-star cast for the English dub, including Glenn Close, Christopher Plummer, and some oddball choices like Paul Shaffer and Penn and Teller (yes, Teller). Apparently deciding his artistic interference was sufficient for a major credit, the film now stated it was “directed by Harvey Weinstein” – an artistic assault if ever there was one. Nonetheless, the film received a major theatrical release with large print ads. This was the era, pre-Disney animation’s comeback, when such a remarkable thing could happen, but something as distinctive – and European – as Gandahar was never going to be a big hit in the U.S. I caught up with it on home video shortly after its release, and my brain couldn’t quite handle the weird rhythms, a reaction very similar to my too-early exposure to Fantastic Planet. About fifteen years later I rented an old VHS tape again, finding it fascinating but also clearly mutilated. I could recognize that there was a movie underneath struggling to get free. Luckily, Eureka in the U.K. released the uncut film on DVD in 2007, allowing English-speaking viewers like myself an opportunity to finally appreciate what Laloux was attempting without Weinstein’s greasy fingerprints all over it. It remains a beautifully bizarre film, asking us to learn its extraterrestrial rules at our own pace – free of any kind of hand-holding narration – and giving us glimpses into its many interdependent cultures that range from the colossal to the microscopic. That even the machines are found to sit on the same time-looping evolutionary chain is key to Laloux’s vision, one he carried through all three of his feature films: we’re all interconnected, and we need to push back our conflicts to truly evolve.