2021 is the 10th anniversary of Midnight Only. To mark the occasion, this imaginary, rat-infested, leaky-roofed theater is raising the curtain on historically important midnight movies.

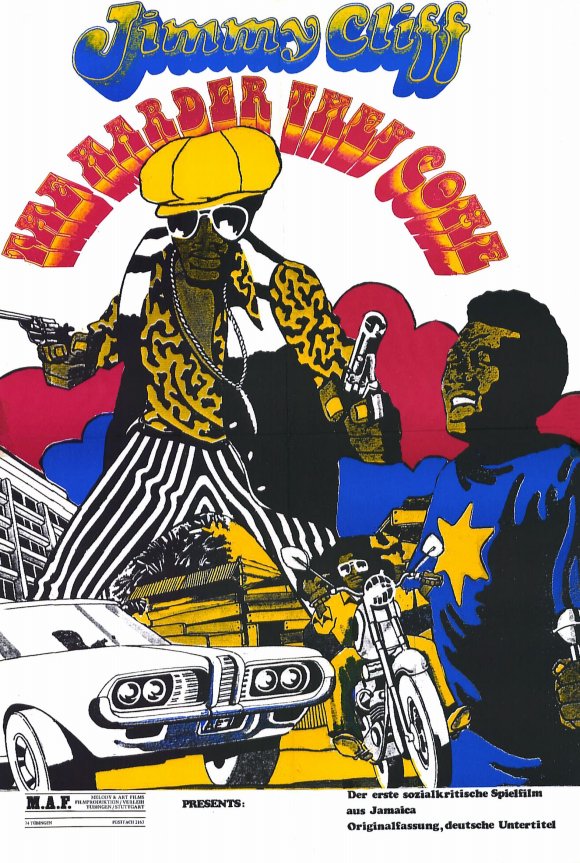

The Harder They Come (1972) was a midnight movie hit shortly after its US release in April 1973, playing the midnight slot for over 6 years at the Orson Welles Cinema in Cambridge, MA. But it stood apart from other long-running films that screened for the late-night crowd. It wasn’t a head trip like El Topo, an ironic revival like Reefer Madness, or a transgressive underground movie like Pink Flamingos. Perry Henzell’s film, shot in 16mm, belongs to the Jamaican streets. The dialogue, spoken by its non-professional cast, is delivered in a thick, export-unfriendly Jamaican Patois. The star, Jimmy Cliff, was a singer who, at the time of the film’s production, was largely unknown outside his native country. And today, the film is chiefly regarded as the one whose soundtrack caused reggae to spread like wildfire outside Jamaica. It was a pop culture seismic event with a distinct Before and After. Bob Marley, a singer since 1962, released his seminal 1973 Wailers record Catch a Fire several months after The Harder They Come‘s soundtrack hit record stores. American and British bands began to incorporate reggae rhythms into their albums. The film’s longevity as a midnight item can be attributed largely to the popularity of its record – it was an opportunity for audiences to see the movie whose disc they were already spinning.

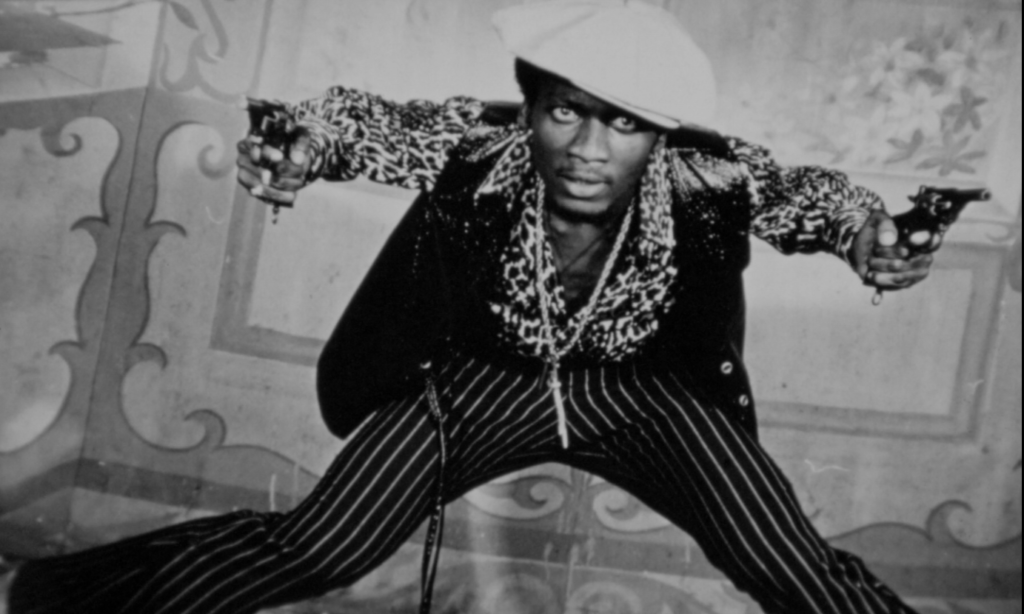

Jimmy Cliff as Ivan Martin.

Inspired by real-life Jamaican gangster Vincent “Ivanhoe” Martin, aka Rhyging, who was shot down by police in 1948, The Harder They Come delivers a contemporary Kingston setting for its Ivanhoe Martin, played by Cliff. Henzell, who co-wrote the film with Trevor D. Rhone, takes his time building toward Martin’s descent into criminal activity. He is, at first, steeped in poverty and scrambling desperately for work. On the advice of his mother he reluctantly takes a job with a strict and fiery preacher (Basil Keane), then exerts his considerable charisma on the man’s young and wide-eyed ward, Elsa (Janet Bartley). A delivery job to the local recording studio sparks Ivan’s interest in recording a single. Elsa loans him the key to the church so he can practice, which enrages her father, driving Ivan back into the streets. To top it off – shades of Bicycle Thieves (1948) – his prized possession, the bicycle he’s been working to repair, has been stolen, and he slices up the culprit’s face with a knife, earning him a brutal whipping by the police. But, catching a break, he does record his song, “The Harder They Come,” for a greedy producer (Bob Charlton) who won’t pay him more than $20. When the song becomes a radio hit, Ivan is already on his way to a life of crime – his friend Jose (Carl Bradshaw) gives him a job running cannabis through town – but following a betrayal and Ivan’s shooting of a police officer, he makes a decision to embrace his popularity among the impoverished community, taking on the police with devil-may-care enthusiasm. An early scene in which he watches Django (1966) mow down cowboys in the mud while the audience hoots and hollers forms the template for his own outlaw hero, albeit one who is clumsier, short-sighted, and casually tempts fate with hubris.

Janet Bartley as Elsa.

Henzell’s choice to make a film featuring an almost entirely Black cast speaking in their own local dialect, concession-free (though the film was subtitled when it was released in the States), fueled the film’s popularity when it was released in Jamaica: a simple choice, but extraordinary representation in line with the film’s message of giving a voice to the invisible. Henzell’s neorealist, documentary-like approach lets his fictional characters walk through unstaged scenes of life in poverty, at one point panning his camera across a landfill where the poor dig through trash while Ivan looks on. Contrasting with such scenes are joyous, carnal moments. Elsa daydreaming during church service of standing nude in the waves, embracing Ivan. Ivan taking her on a bike ride through sunny Kingston. Ivan’s theft of a car from a hotel, speeding into green grass while Henzell’s camera drifts high above. And, of course, the music – Cliff’s title track, plus “You Can Get It If You Really Want,” “Many Rivers to Cross,” and “Sitting in Limbo”; Toots and the Maytals performing “Sweet and Dandy” in the recording studio while Cliff looks on in pleasure; the hypnotic “Johnny Too Bad” by The Slickers. The Harder They Come isn’t quite a reggae musical, but it can stand beside other films of its era, post-The Graduate, that trade a traditional score for pop music. It would be a memorable film without the music – it would! – but the vibrant songs provide the story a resonant heartbeat. The music is Ivan’s soul, keeping him sympathetic through his transformation into a Cagney-like Public Enemy – even through his affair with Jose’s girlfriend, betraying the exasperated Elsa who eventually goes back to live with the preacher. The music also becomes the anthem of the people as they help Ivan escape pursuit from the cops, scrawling messages on fences mocking them. When Ivan inevitably falls – cornered, sweaty and exhausted, but defiant – Henzell keeps tempo, his camera staggering across the sand alongside the antihero, cutting to black as Ivan finally drops to the ground. If Ivan doesn’t get a send-off on the scale of White Heat, it’s because Henzell has kept the film grounded, human-scaled. Because it stays at that level, it soars.