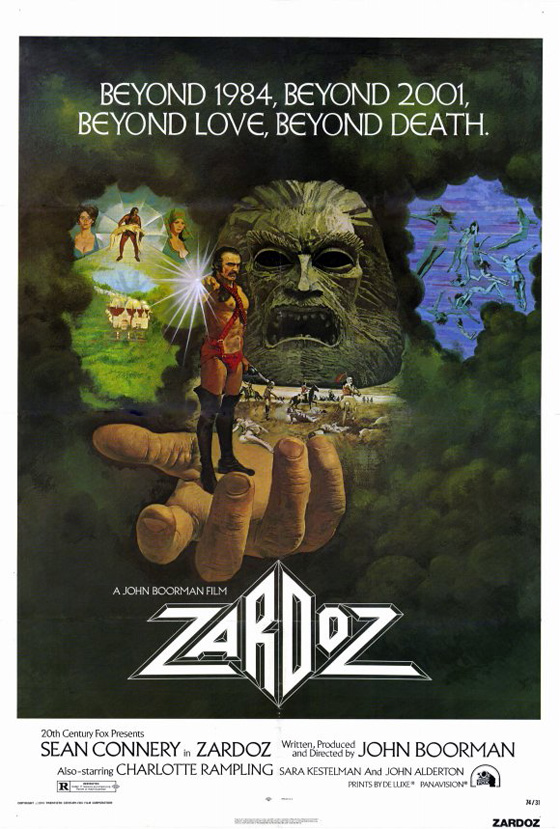

Every time I watch Zardoz (1974) – which, I admit, is becoming increasingly often – I have flashbacks to my first viewing, which made such a deep impression on me as a child. It was being aired on television. A giant stone head with a bearded, fearsome countenance and crystal eyes settled slowly, like a UFO, upon the ground in a misty field. It is approached by chanting warriors, on foot and on horseback, wearing plaster heads resembling the mammoth stone idol, which dwarfs them. Suddenly, out of its mouth pour a tidal wave of rifles. The warriors pick up the guns and fire them into the air. The head lifts back into the sky and sails off, drifting in slow-motion while the credits roll. That I remembered (and a later scene in which a group of immortals sitting at a dinner table communicate via telepathy); when I revisited the film as a teenager I was shocked to recall what did not stand out to my still-forming mind – the god Zardoz intoning that “The Gun is Good. Penis is evil. The Penis shoots seeds and makes new life to poison the earth with the plague of men, as once it was. But the Gun shoots death and purifies the earth of the filth of Brutals. Go forth and kill. Zardoz has spoken.” Of course, these lines were entirely more memorable to a snickering teenager; just as my older self relished the more outré elements, such as the decapitated opening narrator with a black-marker goatee who asks us, “Is God in show business?”, or the sight of a bemused Sean Connery wearing a wedding dress. Flash forward another decade and a half. A Blockbuster Video is going out of business, selling off its inventory. I don’t hesitate to pick up the DVD of Zardoz at a steal. Popping it in that evening, I am shocked to discover: I like this film. A few more viewings, like an addict: no, I love this film.

Arthur Frayn (Niall Buggy), the alter ego of the god Zardoz, delivers a most awkward introduction to the film.

Which is not to say that Zardoz is a masterpiece or without flaws. It is misguided and hopelessly pretentious. Though it sells itself as a satire, in execution it’s wilfully naïve and unintentionally silly. It is the kind of film that could only be made in this particular era, if not this particular moment, heavily influenced by the psychedelic 60’s and lurking in the shadow of Kubrick’s ultra-austere science fiction diptych, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and A Clockwork Orange (1971): note the heavy use of classical music and the languid pace. But unlike many similar efforts in this direction – say, Robert Altman’s sleep-inducing Quintet (1979) – writer/director John Boorman invests himself so personally into his over-ambitious production that, like the hero of the story, he breaks through to a realm entirely unique; and, improbably, the film works. There is a reason the visuals stuck with me as a child, rather than the ridiculous dialogue: these images are the stuff of dreams. Doubtless the film made a deep impression on my imagination. While I was embracing scenes of X-Wing starfighters raiding the Death Star, there was reserved, in one particular pocket of my mind, the concept that giant stone heads could drift slowly through the sky, animated by unknown powers, serving an unknown purpose. And since I didn’t catch the entire film on that viewing – let’s face it, I probably wouldn’t have understood the plot anyway – it remained a mystery, and settled there as a perfect, unsolvable one until I finally found it again in my teenage years and learned the “twist” of what the name “Zardoz” truly meant (which I won’t spoil here, not that it necessarily spoils anything at all).

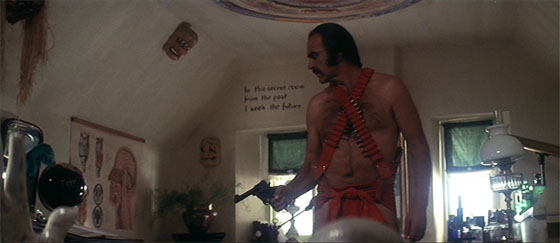

Zed (Sean Connery) discovers the home of Arthur Frayn. The writing on the wall says, "In this secret room/from the past/I seek the future."

Boorman’s always been terrific with powerful images – he was coming off a major hit, Deliverance (1972), and would follow up Zardoz with the visually arresting but incredibly stupid Exorcist II: The Heretic (1977) before making the better-regarded Excalibur (1981). But it should be said that he has an intriguing story in Zardoz, if one chooses to pay attention to the plot rather than the nonstop distractions, such as Sean Connery in that wedding dress. It has the feel of a science fiction Ace paperback from the 60’s. In the year 2293, Earth is divided into two realms: the Outlands and the Vortex. In the savage Outlands, “Brutals” are considered disgusting because they age, have sex, and reproduce. They are kept enslaved (and raped, and murdered) by the gun-wielding Exterminators, who worship the stone idol Zardoz in promise that when they die they will pass into the Vortex and become immortal. Zed (Connery) takes a shortcut by stowing away on the stone head, where he shoots one of those immortals, Arthur Frayn (Niall Buggy), before penetrating the paradise of the Vortex. He discovers Frayn’s home and learns that he created Zardoz to control the Outlands. Subsequently Zed is drawn into a political battle among three of the immortals, May (Sara Kestelman, Lisztomania), Consuella (Charlotte Rampling, The Night Porter), and Friend (John Alderton, Upstairs, Downstairs); when Friend becomes too rebellious, he is punished by his peers, forcefully aged to “Second Level” [corrected – see the Comments] and sent to a retirement community with the senile. While May investigates Zed’s curious origins – she discovers he’s the result of selective breeding instigated by Frayn – Zed inspires a revolt, rousing even the listless “Apathetics” in his attempt to bring down the invisible barrier that separates the elite from the commoners.

Zed is interrogated by the immortals of the Vortex, including Consuella (Charlotte Rampling), Friend (John Alderton), and May (Sara Kestelman).

There are traces of The Time Machine in Boorman’s script, with the immortals somewhat resembling the Eloi, evolved separate from the Morlocks; but these Eloi are intelligent and manipulative, realizing only too late that one of their savages has been manipulating them. Still, this theme could be related more coherently; though Boorman, admirably, lets about twenty minutes of the film pass before the script finally settles into dialogue, once the talking begins it never really lets up. The filmed-at-the-last-minute prologue with Arthur Frayn is genuinely dopey and out of place. Finally, Connery is miscast – there’s too much of James Bond in his eyes for him to convincingly play a savage. Those caveats aside, there’s plenty of wildness and eccentricity on display to keep the viewer engaged, such as Connery alarming/impressing a crowd with his (off-camera) erection, or just the sight of him pulling a cart through a village. There’s a notably beautiful sequence in which images are projected upon semi-clothed and unclothed bodies – representing a psychic transference of High Art – which proves how one can do “trippy” relatively cheaply. An elaborate tracking shot across a bacchanal of Apathetics, which ends with the revelation of the Bride Connery, is impressively staged as well, like something out of a Ken Russell film. And the use of the “Allegretto” portion of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 in A, Op. 92, is undeniably effective, whether in accompaniment to the floating head of Zardoz or the final, eerie time-lapse scenes that take place in a dark cave.

Zed discovers the brain that controls the Vortex.

Ultimately, Zardoz doesn’t need defending. It’s not a forgotten obscurity – it started to build a cult following early through TV viewings like the one I caught, and for decades it was a video store staple; the DVD, released in 2000, even brings us a (slightly apologetic) commentary track by Boorman and a gallery of behind-the-scenes photos and production art. (An HD upgrade would be welcome, and is, I think, inevitable.) I have seen tributes ranging from Zardoz cosplay to a mock-up of an 80’s arcade game that never really existed. Many enjoy it because it’s “so bad it’s good,” though I would argue that the truth is more complicated. Zardoz has a lot to recommend it – some genuine virtues – and it is perhaps easier to enjoy now as an artifact of its time, overreaching, absurd, but unexpectedly rewarding. It never takes too long before the mood strikes me again, and I’ll pay another visit to the Vortex, where Arthur Frayn will welcome me: “I present now my story, full of mystery and intrigue, rich in irony and most satirical. It is set deep in a possible future, so none of these events have yet occurred. But they may. Be warned, lest you end as I!”