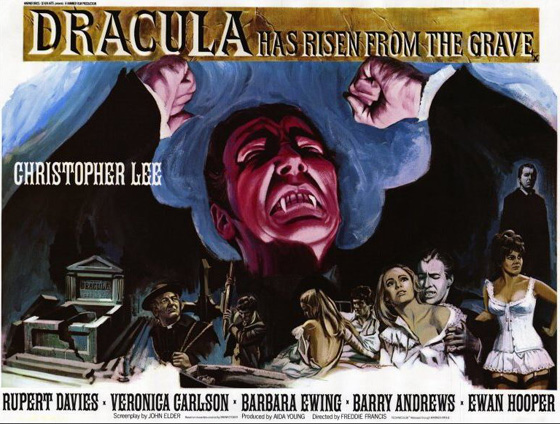

The fourth in Hammer’s Dracula cycle, Dracula Has Risen From the Grave (1968) begins where Dracula Prince of Darkness (1966) ended: with the Count (Christopher Lee) frozen beneath the ice in a mountain stream not far from his castle. (Actually, in the prior film his body came to rest in the castle moat, but in every series entry the landscape shifts ever so slightly.) His evil is liberated by the folly of good intentions: Monsignor Ernst Muller (Rupert Davies, Witchfinder General) goes on a quest with a village priest (Ewan Hooper, How I Won the War) to seal the doors of Dracula’s castle with a cross, thus quieting the worries of the locals, but the priest suffers a bloody fall upon the icy river, and that blood finds its way into the slurping mouth of the Count. Once the newly-revived Dracula discovers that the gate to his home is barred by the Monsignor’s actions, he begins an elaborate act of revenge, placing the village priest in his thrall and targeting the Monsignor’s beautiful young daughter Maria (Hammer “discovery” Veronica Carlson) for corruption. Meanwhile, Maria is courted by Paul (Barry Andrews), whose brazen atheism alarms the Monsignor almost as much as the local vampire situation. Paul’s lack of religious conviction becomes a bigger problem when he drives a stake through Dracula’s heart – a stake Drac promptly removes before resuming the fight. To kill the Count, you’ve gotta believe.

Maria (Veronica Carlson) is visited by Dracula (Christopher Lee).

It is a curious feature of the Dracula films that his villainous actions are so petty – typically concentrating on a single family or circle of friends rather than any grand plot. (The exception is the series’ pulpy conclusion, 1973’s The Satanic Rites of Dracula.) After being killed twice, you’d think that he’d have greater ambitions than a single Monsignor and his innocent daughter. But even in the cycle’s best films, plot is never a particular strength. Atmosphere is what’s important, and to this end, director Freddie Francis delivers in spades. Dracula Has Risen From the Grave was the first film in the series not directed by the brilliant Terence Fisher, but Francis, an Oscar-winning cinematographer, proves an inspired substitute. (Fisher would have helmed, but broke his leg while the film was in pre-production.) Francis takes a rather paint-by-numbers script by Anthony Hinds (under his pseudonym, John Elder) and transforms it into a lush nightmare, with colored filters providing feverish reds, golds, and purples to frame Lee’s arrival in a scene. A spectacular set at Pinewood Studios emphasizes the film’s Bavarian fairy-tale quality. This is a film of hushed bedrooms and raucous taverns of frothing taps, all huddled against the shadowy evil just outside the windows. We don’t often see citizens walking the streets. We see them taking clandestine journeys from one bedroom window to another, because the set – constructed at Pinewood Studios – is a spectacular landscape of touching rooftops, hills of them that disappear into the matte-painted background, calling to mind the German Expressionist films The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and Faust (1926).

Lovelorn barmaid Zena (Barbara Ewing) cares for the inebriated Paul (Barry Andrews).

The film is consistently popular among Hammer fans, though of the Dracula sequels, I prefer the Van Helsing romp Brides of Dracula (1960) and the more subversive Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970). It may be that the ideal sequel can only be assembled from elements of all the films – and from Grave, I would borrow that downright Jungian Pinewood set. I am sure many fans would also find the lovely Veronica Carlson to be indispensable. (Carlson – a talented portrait artist – would subsequently appear in two more Hammer pictures: the terrific Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed and the offbeat, underrated Horror of Frankenstein.) But as central as Maria is, over repeated viewings I find myself absorbed by the tale of the doomed barmaid, Zena, played by a cleavage-touting Barbara Ewing (Torture Garden). I couldn’t care less whether Paul converts to Catholicism to win the approval of Maria’s father and defeat the evil of Dracula. But when the sexy, funny Zena drags a drunken Paul back to his bedroom, plants a kiss on his lips, and then gives him a long, sad look as he fails to react, it’s oddly heartbreaking. She only has a few brief scenes, but her unrequited longing for the young man is palpable, and so it’s dismaying to see her fall under Dracula’s spell and, ultimately, get fed to a fireplace by Ewan Hooper’s corrupted priest. I would have sent the script back for a rewrite. She deserves her own set of fangs, and vengeance – on the drunken sots of the village who leer and harass her night after night. I see her on Dracula’s arm, sporting red and black before riding the carriage back to the castle. That, to me, would be a happy ending; but still, the film does deliver Christopher Lee impaled on a cross, writhing, tears of blood streaking down his cheeks, and in the grammar of the Dracula series, this is a satisfying conclusion.