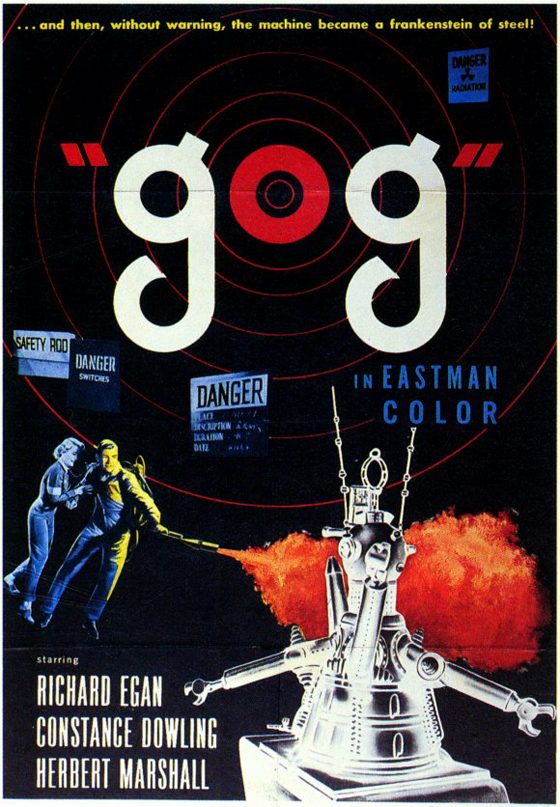

I first read about Gog (1954) as a child, in some library book about robots in science fiction, this film being significant because of its malevolent machines, Gog and Magog, which are apparently named after some apocalyptic prophecy from Ezekiel. (The only other thing I can recall about the book is that it introduced me to Isaac Asimov’s Laws of Robotics.) It’s the third film in a loose series involving the “Office of Scientific Investigation,” following The Magnetic Monster (1953) and Riders to the Stars (1954), all produced and conceived by Ivan Tors, the Hungarian-born playwright and ex-U.S. Army vet who would go on to prolific work in films and TV (for the latter: Science Fiction Theatre, Sea Hunt, and Flipper were among his credits). Each film in the trilogy marked an upgrade: Riders to the Stars, unlike Magnetic Monster, was in color; and Gog, directed by Herbert L. Strock, was in color, widescreen (1.66:1), and 3-D. Produced for United Artists, it was a minor B-movie spectacle, even though most theaters screened it in 2-D, as the format’s “golden era” was on the wane.

Dr. David Sheppard (Richard Egan) inspects the underground research center.

Color was not unheard-of for science fiction films of the 50’s – Destination Moon (1950) and When Worlds Collide (1951) are two notable examples predating Tors’ genre efforts, and Forbidden Planet (1955) and This Island Earth (1956) were soon to come; but given the cardboard nature of so many 50’s SF characters and plots, it’s amazing what a little eye candy can do. Gog opens with color paintings of rockets and space stations that immediately place the viewer in the realm of Galaxy and Planet Stories and Amazing Stories and Fantastic Universe and all those other pulp magazines of the era with their gorgeous, brightly-decorated covers. Then, alas, the movie begins, and we’re about halfway through its 82-minute running time before the two killer robots make their first appearance. The truth is that Gog is not terribly different from other films of its ilk. It’s agog at the new world of Science and Progress and, most of all, Rockets and Robots. So much of the film is given over to a tour of an underground research lab in New Mexico that it gives the impression of a dated Tomorrowland exhibit at Disneyland. We learn about solar energy and its application as a power source (and a weapon). We learn about cryogenic experiments for use in space travel, and a “sound detector” with “electronically controlled tuning forks” that can pick up sound waves from a long distance; this latter device is a silver box with a dozen tuning forks on top of it. When it goes off, a scientist warns, “At this frequency sound can generate intense heat! Open your mouths!” We visit a simulated zero-gravity chamber – produced through magnetism and special uniforms – in which a man and a woman lift each other into the air between ta-daa poses for the camera. “In space there’s no such thing as a weaker sex,” explains stock female scientist Joanna Merritt (Constance Dowling, the future Mrs. Tors). “That’s why I like it here,” replies stock chauvinist protagonist Dr. David Sheppard (Richard Egan).

A scientist is refrigerated to death when the door of an experimental cryogenics chamber swings shut of its own accord.

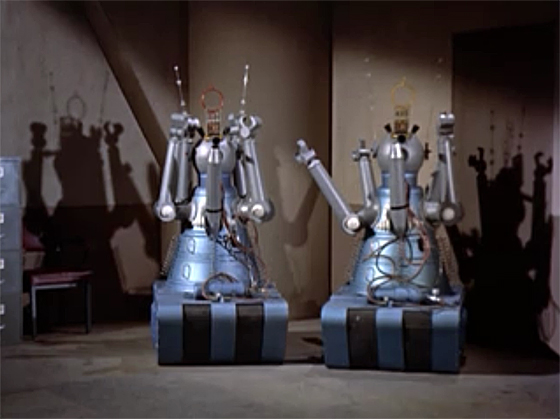

But there are a few scattered murders to liven things up. The film begins with an effective-enough sequence in which two researchers are killed, one at a time, by being locked in the cryogenic chamber and frozen to death. (We learn, later, that they have shattered into icy pieces, a grisly detail the film doesn’t show us.) The suspense is undermined only slightly by the chamber’s low-tech windshield wiper that swipes back and forth across the window to keep the glass from frosting. Later, two would-be astronauts seated in a centrifuge that spins them in circles to simulate space flight are killed when the computer accelerates them to a lethal speed, a scene that anticipates Moonraker (1979). And that tuning fork radar, unsurprisingly, proves a mite too dangerous to have sitting around. When the robots – which somewhat resemble Daleks – threaten to set off a nuclear reaction, Sheppard stops them with a flamethrower, just as the Air Force scrambles to intercept a mysterious craft flying overhead. As is soon revealed, the all-controlling computer within the installation, called N.O.V.A.C. (Nuclear Operative Variable Automatic Computer), contains a receiver – like spyware – that can be operated by enemy jets soaring within a certain distance.

Dr. Sheppard and Joanna Merritt (Constance Dowling) battle Gog.

So although the agency’s own supercomputer has turned against them, a la HAL 9000 or Colossus: The Forbin Project, the real villain of Gog is the Cold War Other. (Communist Russia goes unnamed, but we can pretty much guess.) There is much talk of space travel and the installation’s secret construction of a space station, but exploration of the cosmos and the expansion of scientific knowledge is not the main topic of Gog. No, what’s paramount is gathering data on one’s enemies. Perhaps Tors knew that the Information Age was soon to come – and, with it, increasingly widespread government surveillance – but from the vantage of 1954, this is the best possible New World, no matter that the camera can as easily be pointed within as it can without. The film closes with lines of beautifully naïve optimism between Dr. Van Ness (Herbert Marshall, Foreign Correspondent) and the Secretary of Defense. After explaining that he has independently chosen to launch a space station into orbit at once, Van Ness explains to the (momentarily baffled) Secretary:

“The station will circle around the Earth, and through its eye, we’ll be able to see everything that takes place upon this tired old world – perhaps bring a new life, a new dignity.”

“Nothing will take us by surprise again! When do you launch this space station?”

“In the morning, Mr. Secretary. In the morning, when the air is fresh and crisp and clean.”

Well, what red-blooded American can argue with that?