When R. Crumb met R. Bakshi, the art of animation exploded. And so did (pretty damn close to immediately) their relationship. As recounted in Unfiltered: The Complete Ralph Bakshi by Jon M. Gibson and Chris McDonnell, Bakshi, an animator for Terrytoons who was now grinding away lovelessly at the Spider-Man TV series, was fostering dreams of an animated film for adults – kicking around autobiographical ideas that would later turn into Heavy Traffic (1973) – when he encountered a collection of Robert Crumb’s “Fritz the Cat” underground comix in a stand called The East Side Book Store in Manhattan’s St. Marks Place. With a Fritz-style epiphany, he proposed the idea to his friend and mentor, TV producer Steve Krantz, and then sought out Crumb to strike a deal for the rights. Crumb was interested at first, enough to loan him his sketchbook, but eventually, in the words of Fritz, he bugged out. After the paperwork was drawn up, Bakshi visited Crumb and his wife Dana in San Francisco to have everything signed and finalized. In Unfiltered, Bakshi described what followed:

I hung out with Crumb for a week. Crumb then said, “I can’t take this anymore!” He split! I thought it was all over. I went back to the East Coast. Then Steve Krantz comes into my office about two weeks after and says, “Congratulations, you got the rights!” I said, “But Crumb split!” He said, “No, Dana, his wife, has some sort of power of attorney and signed the deal. We can make the picture!”

Perhaps some insight into Crumb’s behavior might be found in Marty Pahls’ introduction to The Complete Crumb Comics Volume 3 (1988), where he quotes his friend as saying, “I’m a guy who can’t say ‘No’…I find it hard to say, ‘Back off from me, just back off from me.’ I could never do that to this day.” Crumb was recalling to Pahls how he skipped town in order to passive-aggressively break off a relationship with then-girlfriend Dana in 1964 (they were soon married, and divorced in 1978). So Crumb was likely not thrilled that Dana said “yes” while he was still struggling to say “no.”

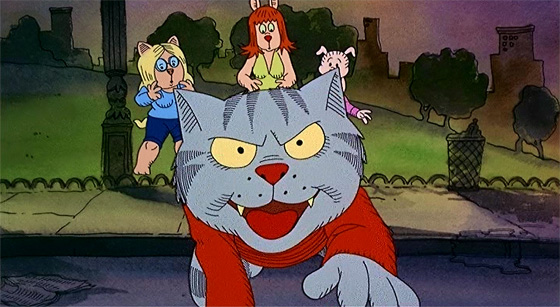

Fritz ignites a riot.

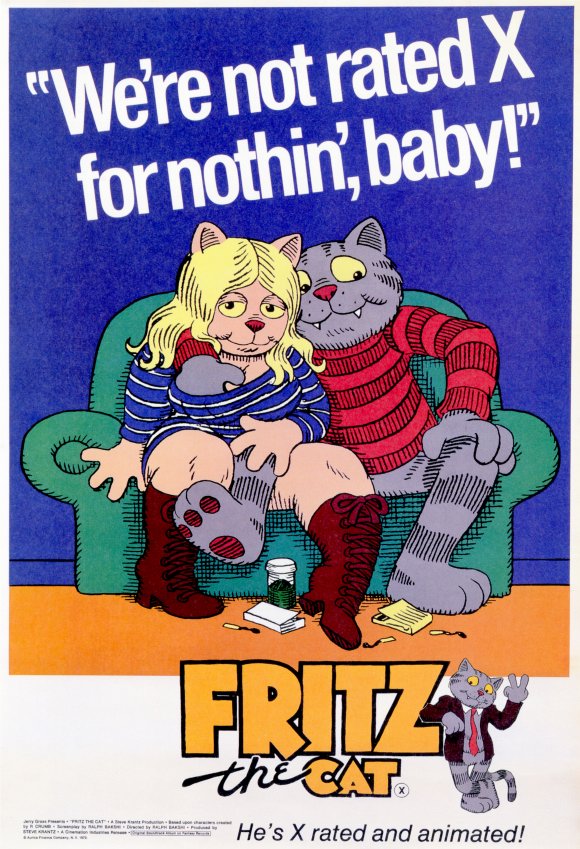

It must have been difficult to envision what would become Bakshi’s Fritz the Cat (1972). There simply wasn’t a precedent for this kind of film. I don’t know what Crumb must have thought the end result would be – although it’s well documented that he loathed what it became, to the extent of creating a cartoon that lampooned Bakshi and Krantz and famously killed off Fritz. Bakshi, to his credit, saw the potential for animation to be more than Disney’s kiddie films, and that has become his lasting legacy. (It should be noted that when Bakshi launched his animated feature career with Fritz, Disney was at a low ebb, having cut back on cost and quality in the 60’s and 70’s to produce films that lacked the magic and artistry of the studio’s golden years. They were at their weakest when Bakshi struck.) But it was also just a very unique time in cinema. Grindhouses, art houses, and drive-ins were delivering adventurous audiences a steady diet of taboo-busting pictures – and when Fritz finally arrived, it was the year of Deep Throat (1972) and the height of porno chic. The tagline “He’s X-Rated and Animated” helped make Fritz the Cat a box office hit. More than just the raincoat crowd were curious to see an X-rated animated film. While Crumb blasted the picture, Bakshi was given enough career momentum to forge a very improbable career as the director of animated films geared toward adults: Fritz the Cat, Heavy Traffic, Coonskin (1975), Wizards (1977), The Lord of the Rings (1978), American Pop (1981), Hey Good Lookin’ (1982), and Fire and Ice (1983) all present an extraordinary run, whatever the films’ individual flaws.

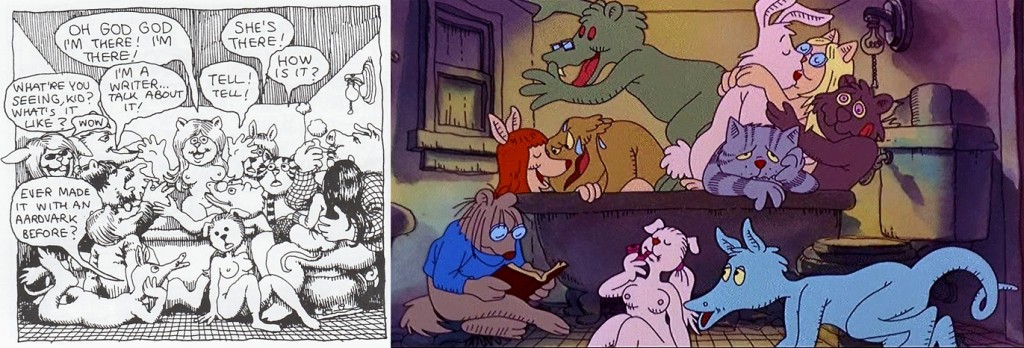

That filmography also gives a good idea of how Bakshi could adapt his visual style to meet the film’s needs. Although Heavy Traffic and Coonskin closely represent his personal cartooning style, Wizards looks like a 70’s Vaughn Bodé erotic comic strip, The Lord of the Rings summons the world of Tolkien’s trilogy with seriousness and grit, and Fire and Ice makes pains to emulate Frank Frazetta’s paintings. It’s clear to me, anyway, that when Bakshi was taking inspiration from the work of another artist, he wanted to do right by them. (How often he succeeded is debatable.) And Bakshi wanted to do right by Crumb. Although Crumb later derided his use of shading using vertical lines, and eventually adapted a more sophisticated cross-hatching technique, those lines are such an integral part of the original “Fritz” strips – and Crumb’s 60’s art in general – that Bakshi practiced and learned them, and they are present in every cel of the finished film. The character designs pay tribute to Crumb’s cast of animal characters; if they’re in the strips, they’re on the screen. (There are even visual shout-outs to other, non-Fritz comix and characters of Crumb’s, so determined was Bakshi to create a living and breathing version of the Crumb universe.) The episodic structure of the film derives from Bakshi’s adapting of Crumb’s original strips, and much of the dialogue is taken verbatim. Maybe Crumb wouldn’t have been quite so upset if Bakshi had been more unfaithful; then he could’ve more easily dismissed it. Instead, this is so close to Crumb’s character that its missteps and miscalculations stand out even more. There’s a lot of Ralph Bakshi in here, too. It was the Bakshi that Crumb likely wanted to excise.

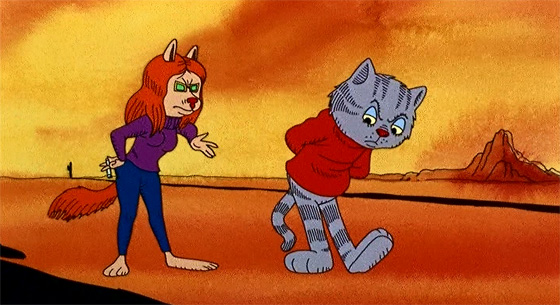

Fritz “bugs out” on girlfriend Winston.

Crumb’s work is built from sex and philosophical satire in equal measure. His Fritz the Cat, who originated in the daydreams of high school sketchbooks, is a self-described poet and artist whose aura of importance is a con – on others as well as himself. He’s fickle and impatient, horny and delusional, ambitious and lazy, a dead-on takedown of a particular type lurking about every campus mall. Crumb worked through his sexual fantasies with Fritz, but pointedly sabotaged most of his schemes. Bakshi’s Fritz, perfectly voiced by Skip Hennant, is actually a solid translation of the character, but the point of view seems subtly skewed. Apart from a very good opening skit in which Fritz seduces a trio of college girls with some nonsense about seeking “the Truth” (leading to the most iconic scene in the film, the bathtub orgy), sometimes it seems that Bakshi buys into Fritz’s bullshit. Much of the film adapts Crumb’s hilarious strip “Fritz Bugs Out,” but it seems to miss the point. In his quest for enlightenment, Fritz accidentally burns down his apartment complex, abandons his girlfriend in the desert, and eventually is beaten senseless by a mob. The killer closing gag is missing altogether from the film: Fritz returns to his friends – whose building he earlier destroyed – as though nothing has transpired (“Hi group!”). By contrast, the closing scene of Bakshi’s film is Fritz having another orgy in his hospital bed with his harem of girlfriends. A better ending would have left Fritz alone, abandoned, and delusionally optimistic – just my opinion.

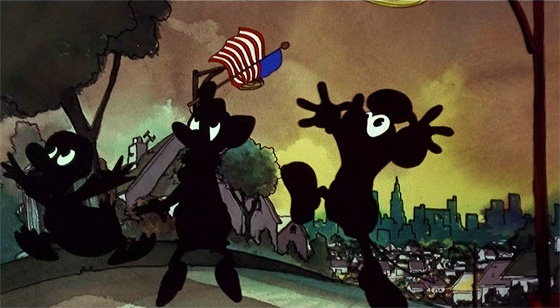

Black crows, far removed from “Dumbo.”

Bakshi’s also more of a vulgarian than Crumb. Their sensibilities are not in perfect alignment, and it’s evident in the film. There’s simply more grime and piss in Bakshi’s universe (the opening credits play over a cascading stream of urine, which finally splashes on the head of a hippie pedestrian). Your mileage will vary, but all this plays much better in Heavy Traffic and Coonskin (really, Bakshi’s two best films), which are in a more consistent style because they spring entirely from the animator’s imagination, compromising to nothing. Crumb’s comics feel like the work of a sensitive, intelligent, and most of all repressed individual. From that repression comes the thrust of Crumb’s cathartic humor. But Bakshi’s just coming from a different place. From an auteur reading of Bakshi’s career, this makes Fritz the Cat interesting: a film of competing artistic points-of-view that is nonetheless very Ralph Bakshi. And you get the director warts-and-all. On the plus side, there are some stunning combinations of live action and animation and a vibrant use of rock ‘n’ roll, jazz, and blues. (My personal favorite has always been the introduction of Harlem with a street crow snapping his fingers to “Bo Diddley,” as the background painting creeps in slowly from the distance. Bakshi had style to spare, and always an excellent taste in soundtrack music.) And out of nowhere, Bakshi can move you: a pool playing hustler’s death is memorably illustrated with a shot of a billiard ball bouncing into a puddle of blood, over and over, in sync with his deteriorating heartbeat. He also includes his own field-recordings of people on the street and Bakshi family members to flesh out scenes with a bit of New York City flavor, an appealing technique he would continue to use in subsequent films. His scenes of black urban life (African Americans as crows, lifted from Crumb, but also used by Disney in Dumbo) walk the dangerous line between the sympathetic and the offensive, but includes some nice satirical touches (Fritz can’t stop spouting off about the race problem – “I wish I were a crow!”).

Bakshi serves up some uncredited cameos in “Fritz the Cat.”

But the film is weighed down by tedious storytelling. Nothing is as harmful to the film’s success as the introduction of labored comic slapstick, primarily in the form of two pig policemen, who arrive just when the film has found a perfect comedic energy; the film never finds that Crumb-ian satirical momentum again. It’s a challenge to turn a comic strip that doesn’t typically last more than a few pages into a feature-length film, and Bakshi doesn’t pull it off. I’ve always found the final stretch, in which Fritz joins a neo-Nazi revolutionary group, to be particularly tough to get through. It’s hard to justify what’s happening and, worse, why we should care. But for all its flaws, the importance of Fritz the Cat can’t be underestimated. Audiences were largely willing to look past its weaknesses, or rather didn’t notice because they were so jazzed by seeing an animated film with so much sex, drugs, and violence. It wasn’t the cartoon porno that the posters implied (that would be 1976’s Once Upon a Girl), but its taboo-busting was as liberating for animation as underground comix were for the comic book medium in the 1960’s. In that way, at least, R. Bakshi honored the spirit of R. Crumb.