“Of course. It’s a big conspiracy.”

“What’s a big conspiracy?”

“Everything.”

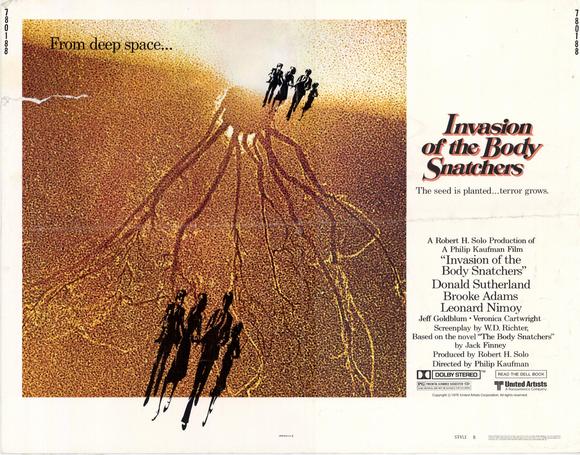

A joking little exchange between Department of Public Health inspector Matthew Bennell (Donald Sutherland) and failed writer Jack Bellicec (Jeff Goldblum) at a dinner party. They’re not talking about anything in particular, and they forget it a moment later. But in Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978), the second filming of Jack Finney’s 1955 pulp SF novel The Body Snatchers, any paranoid suspicion will prove to be correct. Director Philip Kaufman (The Right Stuff), working from a screenplay by W.D. Richter (writer of Big Trouble in Little China and director of The Adventures of Buckaroo Bonzai), creates an increasingly suffocating atmosphere for his only sci-fi/horror film. He deploys every trick in the book to keep the audience in a state of queasy unease. The film arrived amidst the Star Wars fueled boom of science fiction movies, and was also at the vanguard of a surge of nostalgia genre remakes, to be followed by The Thing (1982), The Twilight Zone: The Movie (1985), and Invaders from Mars (1986), among others. But Invasion of the Body Snatchers is also one of the last great 70’s political conspiracy thrillers, a film for the post-Nixon era as paranoid as The Conversation (1974), Three Days of the Condor (1975), Marathon Man (1976), and All the President’s Men (1976).

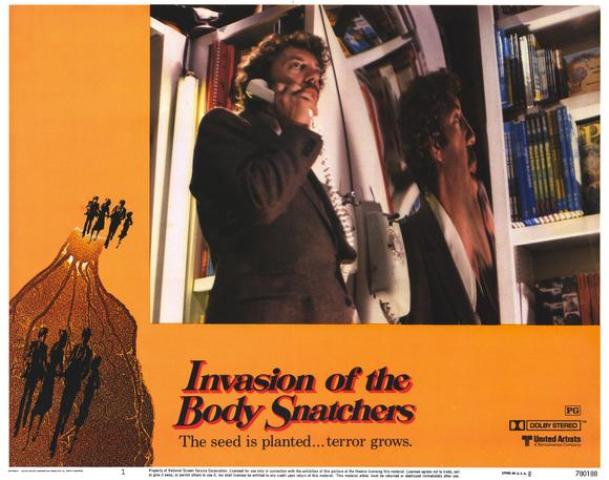

Jack (Jeff Goldblum) and Dr. Kibner (Leonard Nimoy).

Kaufman goes straight to the otherworldly, opening his film on an alien planet where webby spores drift out of the atmosphere, through cosmic space, and finally to Earth, penetrating the skyline of San Francisco, and pollinating amidst plants and flowers. Then it’s back to the everyday. Health department researcher Elizabeth Driscoll (Brooke Adams, Days of Heaven) is living with her dentist boyfriend, Geoffrey (Art Hindle, The Brood), and brings a new flower into their apartment. Shortly afterward, she notices he’s acting cold toward her, and begins to suspect he isn’t really Geoffrey. Her co-worker Matthew is introduced through a peephole, warped to fisheye, and he leans in so that his eye fills the circle. He’s the protagonist of the film, and even he is presented by Kaufman as a kind of alien. He steps into a restaurant kitchen for a surprise health inspection. As the restaurant owner and his chef look on, they are lit by an eerie blue light – the UV light used by Matthew to inspect their pantry. At a bookstore-set party for psychiatrist David Kibner (Leonard Nimoy), a curved funhouse mirror maintains distorted images of the characters in the background. Throughout the film, Kaufman milks paranoia from random disconcerting shots of human beings; humans, after all, are the bug-eyed monsters of Body Snatchers. Robert Duvall has a bizarre cameo as a priest on a playground swing. What’s he doing there? Who knows. Frequently Kaufman will pan or cut to onlookers staring at the camera: at Kibner’s party, or just standing by the street. He uses canted angles, or shoots from just slightly below the characters, so that people lean like stalking animals or just loom. Early in the film, Matthew is seen clipping out a newspaper article: “Webs Shroud the Bay Area.” The webs aren’t remarked upon; instead, we glimpse them in the background of the frame, spilling out of trash cans or being loaded into dump trucks. We might even notice that Matthew’s broken windshield (from some accident we never see, since it’s enough to know that he’s the type who doesn’t give a damn) is cracked in a cobweb pattern, as though the alien webs hover over him, too. And it’s through this cracked glass that we see the original film’s lead actor, Kevin McCarthy, jump suddenly onto the hood and scream “They’re coming! You’re next!” in recreation of his famous moment from 1956. It happens early enough in the film that we can enjoy a slightly goofy self-referential moment – yet Kaufman reestablishes his tone quickly. McCarthy is violently run down, and Sutherland and Adams, horrified, drive by the bloody scene and its crowd of gawkers.

Matthew (Donald Sutherland) and his funhouse mirror reflection.

It’s significant how much time is spent before we actually see the pods, and then how much time before gooey special effects are unleashed. This film’s effects are a perfect example of how much more impressive practical effects can be over CGI. My wife’s shouts of “Eww!” last night are the kind of reaction CG animators can only wish they could provoke. You can reach out and touch these fetus-birthing pods. One notorious scene late in the film, involving a banjo-playing hobo, his banjo, and his dog, stuck with me for years after I first saw it. (It’s the look in his eyes. It’s the goddamn look in his eyes and the casual speed of that dog. I know it’s just goofy to some, but even during this rewatch I almost fell out of my seat.) Kaufman builds slowly to all these big reveals. Apart from the opening credits sequence, you don’t see anything overtly fantastic for a good long while, and yet you’re constantly aware that something is very wrong in the streets and apartments of San Francisco, as he reminds you from one shot to the next. One of the great ideas of Kaufman’s film is that Elizabeth has no logical reason to suspect that her boyfriend isn’t her boyfriend, and that Dr. Kibner’s explanation is the most likely answer: that her brain can’t process the simple fact that her relationship is falling apart rapidly. Sutherland and Adams share a nice private moment drinking wine together. They flirt and know they’re flirting and know it’s ridiculous that they’re flirting, all at once; their longtime friendship and casual intimacy feels authentic. Including scenes like this (and casting great actors – I mean, just look at this cast) guarantees that we will be truly gutted when their personalities are suddenly drained away. Don’t fall asleep, they tell each other. If you do, the pod will absorb you, and you’ll be replaced by a duplicate without any capacity for empathy or love. Note that in the film’s epilogue, alien colonization is simply represented as office workers silently going about their tasks – yet the audience is on the edge of its seat looking for traces of humanity. This is what great science fiction does: transforms and recasts the everyday.

One of the pods gives birth.

The score by jazz pianist Denny Zeitlin – his only film composer credit – is cleverly structured as a split personality. The alien, or the threat of the alien, is represented with electronic music, often pulsating, or blatantly discordant. It picks up where the experimental score for Forbidden Planet (1956) left off. When the humanity of the characters is on display, he uses traditional instrumentation, piano or an orchestra. (Incidentally, the banjo music of the homeless man is actually being played by The Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia.) Think of the scene where Jack and his wife Nancy (Veronica Cartwright, Alien) risk capture by drawing the attention of a mob of pod-people; the orchestra surges and the electronic menace subsides. All of this builds toward a climactic scene in which Matthew tries to find a means of escape with a docked cargo ship. Speakers from the ship are blasting “Amazing Grace” with the bagpipes of the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards. The inspiring and very human moment is cut short by the squeal of radio static, and then the voice of another pod person dully barking commands. Note, too, that the ending credits feature no music whatsoever. By now, everything has been absorbed, flattened, and nullified.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers has been a perennial staple of home video, and its latest incarnation is a spiffy Blu-Ray from Shout! Factory’s Scream Factory line, another of the label’s efforts to provide the definitive edition of a beloved cult title. Supplements are abundant, and the film looks great in high definition: you can see every shivering white thread creeping up Sutherland’s arm. Incidentally, there’s currently an entertaining Body Snatchers quasi-remake on network TV (produced by Ridley Scott): the political satire BrainDead starring Mary Elizabeth Winstead. In a small role is Invasion of the Body Snatchers‘ Brooke Adams.