“It’s like the thing that’s taking over my body no longer needs human blood…”

Messiah of Evil (1973) is that rare drive-in movie which captures the mesmerizing, almost stream-of-consciousness horror of Herk Harvey’s Carnival of Souls (1962). It also rises above its stripped-bare budget and mostly-locals casting with a screenplay so literate and intelligently crafted that it shines as bright as a razor, a worthy successor to Night of the Living Dead (1968). That screenplay is by the film’s director, Willard Huyck, with his partner Gloria Katz, who together would share credit with George Lucas on the script for American Graffiti the year that Messiah of Evil was released. The pair also wrote Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, and later Huyck completed his brief list of directorial credits with the notorious Howard the Duck. But to go back to Huyck and Katz’s indie roots is a revelation. Messiah of Evil is a brilliantly creepy little film, chock full of unsettling images, black humor, and a palpable sense of danger. “Lovecraftian” is an overused term, but this is an exemplary of the type, without adapting any Lovecraft story directly or name-checking any familiar elder gods. As with John Carpenter’s In the Mouth of Madness (1994), it’s narrated by someone committed to an asylum, recounting the events that have led here; like that story, it’s a journey to an eerily empty town that has been consumed by murderous insanity and a feeling of impending apocalypse. The town is on the California coast, was formerly named New Bethlehem, and is now called Pointe Dune. One character speculates that if all the cities of the world were rebuilt tomorrow, they would be exactly like this one: quiet, empty, and containing a “shared horror.” As though nothing green can ever grow again, and the rest of the world just hasn’t caught on that it’s dead, or dying.

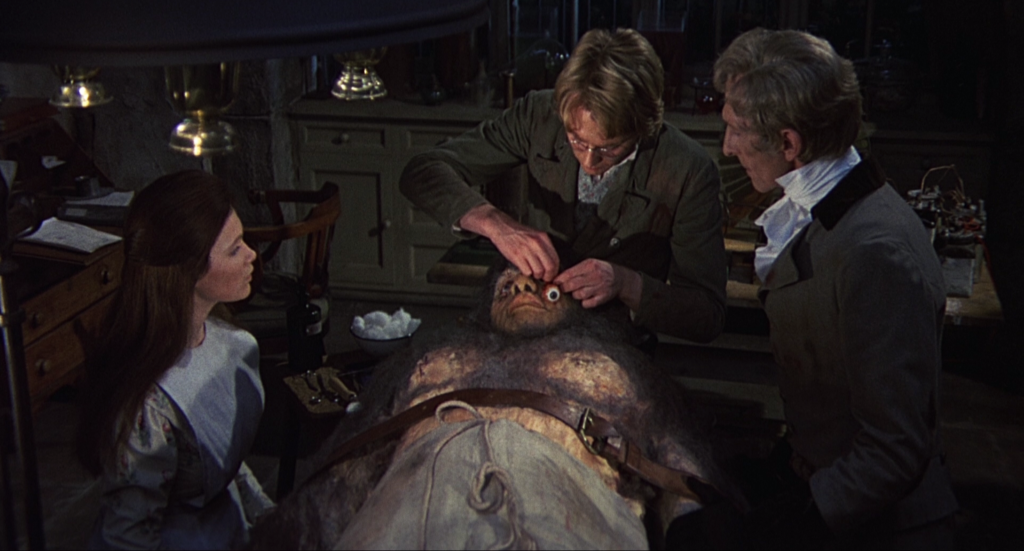

Elisha Cook Jr.’s cameo as the homeless Charlie, a witness to the town’s decay.

Arletty (Marianna Hill, High Plains Drifter) is searching for her father, an artist who’s gone missing in Pointe Dune. Along the way, late at night, she stops at a gas station where the attendant is firing a pistol into the darkness. Wild dogs, he complains. He fills up her car and asks why she’d want to go to a place like Pointe Dune, before he encounters an albino (Bennie Robinson) with a wandering eye and a pick-up crammed with corpses under a tarp. Later, in town, Arletty meets a trio of sensuous hippies, one of whom, Thom (Michael Greer, Fortune and Men’s Eyes), claims to be the son of a Portuguese aristocrat. He’s been investigating Pointe Dune’s mysterious history, including the appearance 100 years ago of a “blood moon” and a “dark stranger” who brought an evil religion with him. When Arletty first meets Thom, he’s interviewing a homeless man named Charlie, played by legendary character actor Elisha Cook Jr. (The Maltese Falcon, The Killing, Rosemary’s Baby). Memorably, he recounts his birth as Arletty enters the scene: “Momma delivered me herself. She took me from between her legs. Bloody little mess. She was about to feed me to the chickens, and Daddy said, ‘Maybe we could use a boy, Lotte.'” Arletty takes up residence in her father’s empty studio, surrounded by his art – much of it murals on the walls, crowds of figures that seem to stare piercingly at the characters (even, uncomfortably, surrounding the bathtub). Thom and his two companions Laura (Anitra Ford, Invasion of the Bee Girls) and Toni (Joy Bang, Play it Again, Sam) wander in, and Arletty lets them stay. Toni can’t receive any nearby stations on the radio; somehow, she finds one broadcasting from Idaho. Outside, the madness hides in the corners of vacant, fluorescent-lit stores, lonely streets, and chilly beaches, waiting for them to wander by accident into dangerous cul-de-sacs.

A gathering for a raw meat buffet at the grocery store.

This sets up two grand, memorable scenes of true horror. First Laura, having just unwisely accepted a lift from the albino – he offers her a rat to eat – takes shelter in a grocery store where the few inhabitants steal glances at her as they pass behind corners. Suddenly she comes upon them in the meat section, ripping open the raw packages and greedily dining on the red contents like Romero’s zombies. She makes a desperate escape attempt down the grocery aisles. Next it’s Toni’s turn, cast out of the house by Thom so he can spend some time with Arletty alone. She buys a ticket at the local cinema (the marquee bears the apt title of a 1950 James Cagney crime saga, Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye). Only a few people are seated in the giant theater. In one of the great edits in horror film history, just as the lights dim she sees that the figure in the front row has turned to face her – he’s lit for about a frame of film before he’s cloaked in the shadows. Toni tries to lose herself in the movie. As a trailer for a Western unspools, more people enter the theater – one by one, slowly filling the rows behind her. Finally, two sit down next to her. When she looks over at them, they gaze back with blood running from their eyes.

Arletty (Marianna Hill) and Thom (Michael Greer).

Interspersed throughout the film are scenes of Arletty bent over her father’s diary, reading his rambling entries – we hear his own voice reading his words, scored to the electronic soundtrack by Phillan Bishop. And Arletty begins to lose her grip: she sees one of the paintings shedding a tear of blood, and finally observes the tell-tale sign in her own reflection. Her father turns up dead on the beach, crushed by his own bizarre sculpture, as though he were trying to create some modern art temple to ward off the century-old evil. We do, finally, receive a period flashback which “explains” the evil to an extent, but it contains that slippery logic that Lovecraft wielded so well. Cannibalism enters the picture, but it’s also something more than that: a “new religion” that apparently invades the minds of anyone passing into this particular coastal community. And all of it plays with a casual surrealism that is heightened by the screenplay, Arletty’s narration (from the asylum) mixing with her father’s, as she makes observations like: “The art dealer was blind. Her fingers moved like a pale spider over my face.” Only in the final moments does the film seem to flail a bit, to create an ending in the editing room by showing us highlights of what we’ve already seen. But the film’s peculiar power remains undiminished. Messiah of Evil lifts the banality of a dying community – empty parking lots, boarded-up storefronts, the dead-eyed workers left behind – into the realm of cosmic horror.