Continuing our foray into the colorful world of Russian fairy tale cinema, The Snow Maiden (1968), like its protagonist, has a foot in two different worlds. It has touches of the candy-coated, hyper-imaginative fairy tale films of Aleksandr Ptushko (Sadko, The Tale of Tsar Saltan), but with an introspective and adult tone, slower pace, and charged, eerie atmosphere more in tune with 60’s art-house fantasy films like Juliet of the Spirits (1965) and Kwaidan (1964). If it doesn’t compare in impact to those films, perhaps it’s because it’s a commissioned Soviet work paying straight-faced tribute to one of the Motherland’s great artists, Aleksandr Ostrovsky, who wrote the 1873 play The Snow Maiden, based on an old folktale. (The film was released in honor of Ostrovsky’s 150th birthday.) Or perhaps The Snow Maiden simply needs to choose between those two worlds: does it want to be a Russian fairy tale genre film, replete with handsome men operatically singing, or does it want to be an art film with more raw, adult themes?

One of the spirits of the wood, pledged to protect the Snow Maiden from harm.

Two key players keep the film from being just another fairy tale. One is the director, Pavel Kadochnikov, a veteran Russian actor who also appears in the film (looking quite a bit like Sean Connery) as the Tsar Berendey. Kadochnikov, like many actor-turned-directors, focuses his attention on the emotions of the characters; the Snow Maiden might be the daughter of Father Frost, but he only puts in a brief cameo at the beginning of the film, deliberately obscured by a snowstorm. There will be no huts with chicken legs here, nor three-headed dragons. The second key player is the composer, Vladislav Kladnitsky, whose score borders on the experimental, and does much to provide that particular eerie feeling. It’s completely at odds with the festive folk music which the villagers celebrate throughout, another element of the film’s strange dissonance. (One of the most famous incarnations of this tale is the 19th century opera by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Kladnitsky seems to consciously take his score in the extreme opposite direction.)

Young maidens eagerly dote on the visiting Misghir (Boris Khimichev).

In medieval Russia, the Snow Maiden (Yevghenia Filonova) refuses to depart with Father Frost to Siberia for warmer months, lured as she is by the happy villagers enjoying a Shrovetide celebration in the snow. He agrees to let her enjoy spring with the villagers, but only after entrusting her safety to the “wood genies” of the forest, strange, moss-covered creatures who emerge from shrubs and swamp. In the village, the Snow Maiden falls under the thrall of an elderly couple in poverty who wishes to sell her beauty for a rich dowry. Though the frosty Snow Maiden cannot love, she quickly becomes attached to the young singer Lel (Evgeniy Zharikov), who is smitten with her, and whose songs she admires. When a rich merchant, Misghir (Boris Khimichev), arrives (also singing) from upriver, he quickly scorns his fiancée Kupava (Irina Gubanova) for the Snow Maiden. Tsar Berendey tells Misghir that he cannot have the girl unless she returns his affections, but the merchant only frightens the snow-spirit; at one point Misghir becomes so desperate in his obsession for the unobtainable Snow Maiden that he nearly rapes her. Lel, meanwhile, falls in love with Kupava, and the Snow Maiden, despairing, turns to her mother, Spring, to learn the gift of love. In doing so – as the old folktale goes – she melts away, seen here in a symbolic shot of the maiden dissolving in a beam of sunlight. Misghir dies of grief.

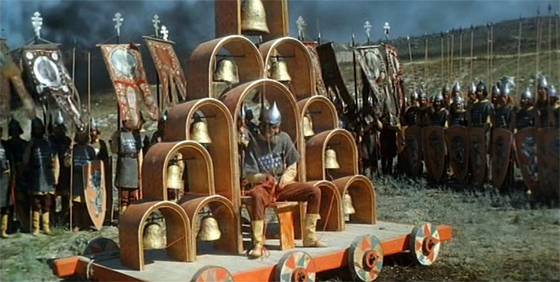

The people of the village worship Yarilo, the Slavic god of the springtime, symbolized by the Sun.

Kadochnikov films most of this in an appropriately somber manner, but despite his evident intention to deliver a more serious fairy tale, he also gives the audience their expected comic relief characters (three brothers, ancillary to the plot), extraneous songs, and wacky monsters (the wood-sprites look like something from the world of Sid & Marty Krofft). Much time is spent among the characters of the village and the developing love triangles, but in these scenes I found myself more interested in the beautiful costumes of the maidens and the elaborate wooden architecture of the village; the script itself couldn’t hold my attention. At just ninety minutes, the film feels too long. Otherwise, it requires more elaboration of ideas floated during the final scenes – such as the wood-sprites coming to the Snow Maiden’s protection and dazzling Misghir with their magic; or the arrival of her mother, striding over water like the Lady in the Lake. Or, to the point, the film needs to examine the import of a fairy tale in which a woman is given the gift of love for a man wholly undeserving. The Snow Maiden fails to satisfy on those points. It’s one of the more interesting variants of this genre, attempting to appeal as much to adults as to children, but perhaps it wouldn’t melt from the memory so quickly if it committed fully to one or the other.