True story. When I was a kid I had an imaginary friend named Jody. I have no idea where I got the name from, but for a few years – and while expanding my imaginary clan of friends and giving them different names like the Smurfs – Jody and I hung out and played with my Star Wars figures. Here is the difference between my imaginary friend Jody and the invisible character named Jody whom the little Lutz girl befriends in The Amityville Horror (1979): my Jody did not cause rocking chairs to rock, or instruct me to leave my babysitter locked in the bedroom closet, and – perhaps most critically – my Jody was not a giant purple pig with glowing red eyes. I would have remembered that. It is strange, though: not the coincidence that my imaginary friend shared a name with the one in accounts of the haunting of Amityville in Jay Anson’s 1977 book The Amityville Horror: A True Story, but that a child’s imagination would crave something to be there that isn’t. The child craves it to the extent of constructing an entire narrative about this friend, all the while holding in the head two conflicting facts without bothering to resolve them: this is not real and this is real. It’s the same, I suppose, with a child who plays with a doll, combing her hair, dressing her up, and bursting into tears when she’s accidentally dropped to the floor. This child knows the doll is not a real person, but it does not matter, because she would prefer to believe it. The lie is too appealing, so she holds the truth and the lie in her head like Orwellian doublethink. You know what, I just realized something as I wrote this. My imaginary friend was named Joby, not Jody. Look, it was a very long time ago, and maybe for a few minutes there – actually, for the duration of watching The Amityville Horror, when I had convinced myself that my friend was named Jody – the lie my brain was telling myself was simply too appealing. So, yeah, True Story, I had an imaginary friend. That’s not as interesting, so would this have been better if, soon as I remembered the facts properly, I’d just ignored them? Come to think of it, my friend was a giant purple pig with glowing red eyes. “Get out!” he’d tell me, and we’d laugh and play with my Star Wars toys.

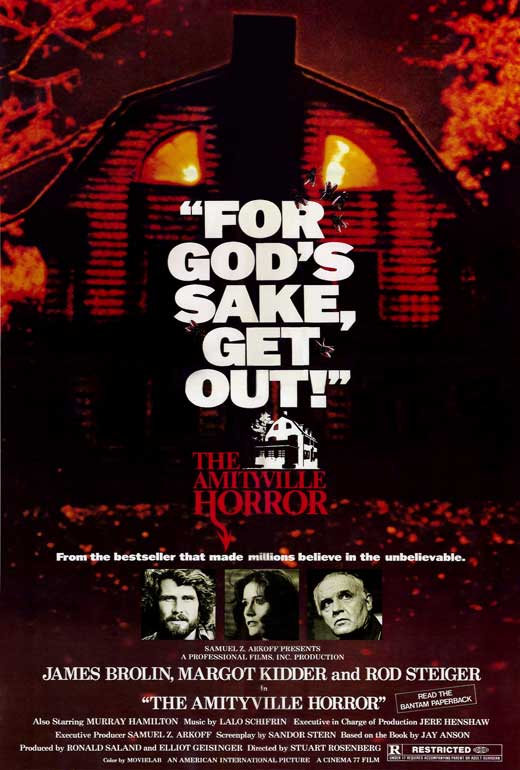

The Amityville house as depicted in the film, with malevolent "eyes."

Truth and no consequences? The Amityville Horror: A True Story was a colossal bestseller. It relates the story of George and Kathy Lutz, who purchased a home in Amityville, Long Island, after the previous owner, Ronald “Butch” DeFeo Jr., murdered six members of his family with a .35 caliber rifle while they slept; the Lutz family only spent 28 days in the house before leaving, claiming eerie and frightening experiences within its walls forced them out. Flies manifested and clustered, even in the dead of winter. A crucifix inverted itself. Ectoplasm oozed out of keyholes. George Lutz would find himself consistently waking at 3:15 in the morning, the estimated time of the DeFeo murders. The Lutzes’ daughter acted peculiar with her imaginary friend. A priest visited the house to perform a blessing, and claimed a voice told him to “get out.” On their last day at the house, the apparition of a hooded figure was glimpsed on the upper landing. And so on, and so on. Anson relied upon the Lutzes’ tape-recorded testimonials about their supernatural experiences at 112 Ocean Avenue, packaging the facts into a page-turner, including applying a sensationalistic title borrowed from a classic H.P. Lovecraft story, “The Dunwich Horror” (about a corrupt family that breeds with an inter-dimensional cosmic being). Many of the details recall The Exorcist, both the 1971 book and the 1973 film, which were sensations in the years prior to the Lutzes moving to Amityville, and led to a revived interest in the occult and the Satanic – similarities which have led to skepticism.

George and Kathy Lutz (James Brolin and Margot Kidder) consider purchasing a new home.

Facts are confused by countless allegations over the decades. Before contacting Anson about writing their story, the Lutzes had already reached out to William Weber, an attorney for the imprisoned killer Butch DeFeo, stating that the house was haunted and that DeFeo might have been so influenced to commit his crimes. Allegedly, Weber tried to have the Lutzes sign a contract to participate in his own planned book about the DeFeo case, but they grew squeamish for a number of reasons, including that they would need to participate in whatever publicity Weber and his associates arranged (they have frequently claimed they desired privacy), and that DeFeo himself would see financial gain from the book’s sales. The Lutzes proceeded to work with Anson on a writing project they could control, and sued Weber and his associates for invasion of privacy – and other concerns – after he commissioned a writer to produce an article on the Amityville haunting for a newspaper (one year ahead of the publication of the Amityville Horror book by the Lutz-approved author, Anson). Weber and his associates countersued, and ultimately Weber claimed that he collaborated with the Lutzes on the story of the hauntings, concocting their accounts “over many bottles of wine.” In this scenario, Weber wanted to get his client a retrial (DeFeo was claiming at one point that a figure with “black hands” passed him the rifle and coerced him into murdering his family), and the Lutzes would find an end to their financial worries. During a 1979 hearing, the Lutzes’ suit was dismissed, the judge stating his opinion that the book was largely a work of fiction and that Weber’s apparent involvement was troubling. This has been enough for some to close the case on the Amityville house, though others allege that Weber had every reason to lie, since he was claiming in his countersuit that the Lutzes broke an oral contract with him to participate in his own DeFeo book. With interest so high in the Amityville case, critics and skeptics went to work, and the foundation began to quake even further. The Anson book claimed the Lutzes discovered pig-like hoofprints in the snow outside their house, but records show there was no snow on the ground on that date. Subsequent owners of the house found no signs of the damage to doors and windows as indicated in the book, nor have they experienced anything supernatural. Books and documentaries have tried to dismantle the case and expose it as a hoax, but some have only spiraled the topic further into the bizarre: the recent My Amityville Horror (2012) limits its tale to the Lutzes’ grown son Daniel, who at one point claims that his father dabbled in the occult and is responsible for the subsequent hauntings. Rather than attempting an objective investigation of the events, it clouds them even further.

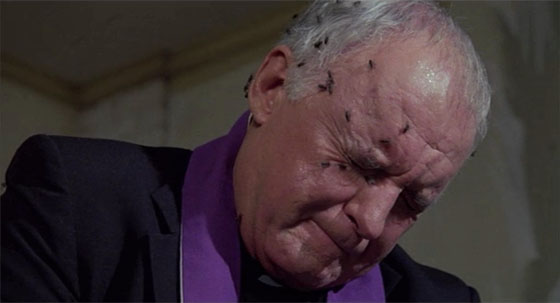

Father Delaney (Rod Steiger) witnesses a manifestation of flies in the Lutz home.

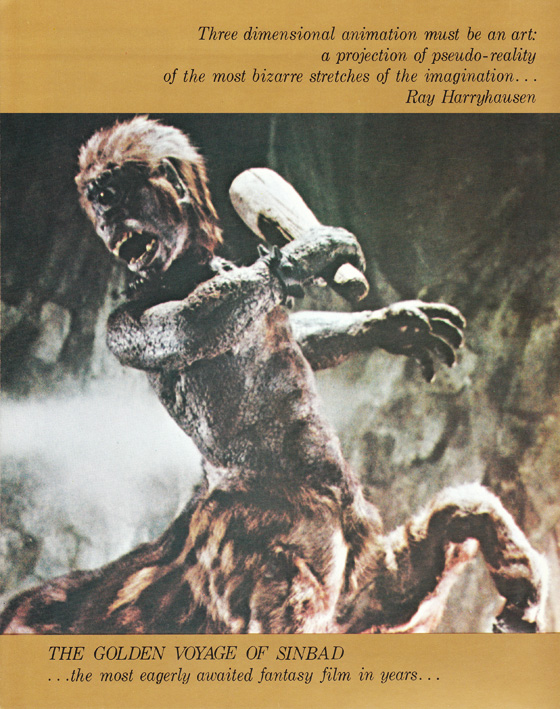

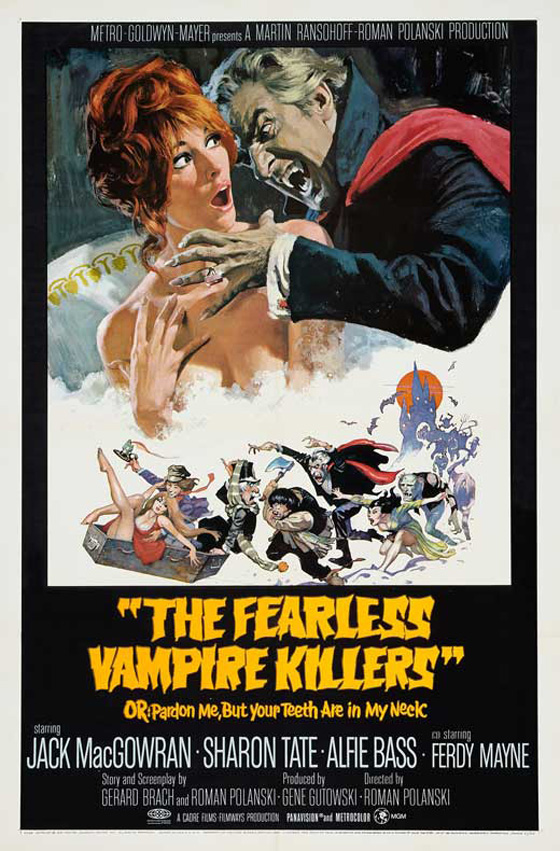

The film adaptation, unsurprisingly, adjusts the facts to tell its own version of the story, though not as much as its many sequels and spin-offs (and 2005 remake) would. Directed by Stuart Rosenberg (Cool Hand Luke) for American International Pictures at a budget of $4.7 million, it grossed in excess of $86 million, an unusual feat for a studio best known for exploitation fare like Blacula (1973), The Food of the Gods (1976), and, yes, The Dunwich Horror (1970) starring Sandra Dee and Dean Stockwell. James Brolin (Capricorn One) and Margot Kidder (Superman: The Movie) portray George and Kathy, an attractive pair who move into the Amityville house, built on a canal with a boathouse, because it’s a steal for the financially-strapped couple: the DeFeo murders – graphically depicted in the film’s opening minutes and frequently shown in flashback throughout – have sufficiently devalued the home to bring it within reach. Lalo Schifrin’s memorable score evokes an eerie lullaby somewhat reminiscent of Krzysztof Komeda’s for Rosemary’s Baby (1968) – so we know at once that this couple’s happiness will be undermined by something sinister. Soon enough, friend of the family Father Delaney (Rod Steiger, In the Heat of the Night, The Illustrated Man) finds himself trapped in an upstairs room where flies gather along the window and swarm over his face; a door finally swings open and a voice tells him to “Get out!” But all this happens without the Lutzes about, and when he subsequently tries to call and warn them, the line goes to static.

George Lutz begins behaving erratically during his stay in the house.

The film implies that George Lutz, who is revealed to bear an uncanny resemblance to DeFeo, is becoming influenced, if not possessed, by the house. Increasingly shaggy and wild-eyed, he begins to snap at Kathy and the kids, as his finances begin to unravel and his checks bounce. He aggressively chops up firewood in the yard, at one point hurls his axe long-distance into a tree trunk, and finally turns on his family, swinging the axe at a barricaded door in a scene that anticipates the following year’s The Shining (1980). Other disturbing events have been occurring, including a babysitter becoming trapped inside their daughter’s bedroom closet – even though the door has no lock – while the girl simply stares forward, later claiming that she was only doing what “Jody” demanded. Kathy walks into her daughter’s bedroom where her girl is playing with Jody, an empty chair rocking of its own accord, and when she claims that Jody was frightened and fled out the window, Kathy looks – and sees red eyes glowing back at her from behind the glass (a scene reminiscent of Suspiria). Tar-like black sewage overflows from the toilet. The family dog claws obsessively at a wall in the basement, and when George breaks through it, he finds a secret room with walls painted red, and glimpses the ghostly image of his own face staring back at him. He comes to believe that a tribe of Indians buried their mentally ill on the grounds where this house was built. Later he sees a giant pig with red eyes in the upstairs window. Finally, on the last night, the walls begin to bleed.

Bleeding walls and stairs.

The truth, the truth – the truth is that The Amityville Horror is an inferior haunted house film, and although it’s competently made, there is little here to distinguish it apart from Schifrin’s score and the well-cast leads. It’s justified in building slowly to its supernatural events, but when those events are disappointing and not particularly scary, the entire framework crumbles. Take, for example, the first major scare of the film: Father Delaney’s encounter with the flies in the locked room. Director Rosenberg spends a long time showing the flies accumulate, while Steiger simply sits there, dabbing at sweat. He doesn’t seem particularly concerned, probably because he needs to remain very still so the flies can be arranged on his face. The scene seems to take an eternity. So, too, do all subsequent scenes with Father Delaney, which mostly involve him staring lethargically at ringing phones or screaming at the top of his lungs at young Father Bolen (Don Stroud, The Buddy Holly Story); though notably Murray Hamilton (Jaws) turns up to lecture him, and seems as though he’s about to explain why the beaches of Amity(ville) must remain open. Although the scene with the babysitter invokes some chills, and the appearance of the pig is memorably bizarre, most of the film fails to connect with the necessary impact, and one simply waits for the family to wise up and get out.

"Jody" in the bedroom window.

The problem with The Amityville Horror may not lie in how it strays from the book, but actually its adherence to it. Most of the key events originate, in some form or another, with its source material, and like the dutiful, obligatory bestseller adaptation that it is, it serves up those key moments so the audience can recognize them. It would have been a scarier film if it strayed, if it invented. The red room in the basement is not adequately exploited. The actual red room is a bit of a non-starter: subsequent owners have pointed out that it’s just a small closet in the basement, not hidden in any way. But the premise is eerie enough that a good storyteller wouldn’t be able to resist; this should be the portal to Hell that the film briefly claims it to be. And the disconnected theories about what is haunting the house – mentally ill Indians, a ghost pig, Satan – ought to be brought together into a single cohesive theory. (If the hooded figure had been imported, the story would have been even more confused.) The film tells us it’s based on a true story, and audiences flocked to it for its “truthism.” A bald-faced lie might have told an even better yarn, maybe one that would have been a significant film for the horror genre rather than just a hit movie that spawned lots of sequels. The Shining is based on a novel, not a true story, but it has a story to tell and tells it well. The film resonates more deeply because it doesn’t hitch itself to something artificial that would hinder its storytelling.

George sees an apparition when he uncovers the "red room."

I had an imaginary friend named Joby. Joby did not talk to me, unless I put the words in his mouth. Joby didn’t make rocking chairs rock. But if I’m at a campfire with some friends telling stories, Joby is going to be Jody, the Amityville Horror ghost, dammit. (Granted, I would have to make up a lot of facts to make that lie work. Perhaps I should just come up with something else.) The recent film The Conjuring (2013), which deliberately invokes The Amityville Horror and its surrounding, 70’s-era phenomenon, is “based on a true story” from the files of Ed and Lorraine Warren, a demonologist and a psychic who investigated a number of supernatural events, including, famously, the Lutz case. I really enjoyed The Conjuring, but when it was over, I took the “based on a true story” about as seriously as I did the claims of the Coens’ at the start of the fictional Fargo (1996). While watching the film, I rarely thought to myself, “Oh, this happened, this is true, apparently.” What was important to me was the story was well-told and genuinely scary. When it comes to the importance of the Truth, it only depends on why you think you need it.