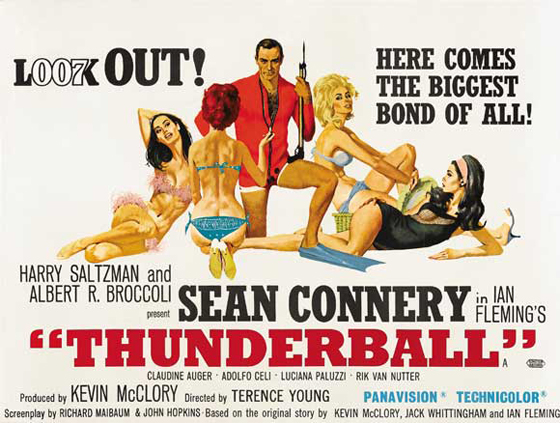

“Merry Christmas, 007,” says Telly Savalas, holding a cigarette to his wolfish grin. He’s Ernst Stavro Blofeld reincarnate – a more robust, athletic, and considerably less scarred Blofeld than when we last saw him, when he was played by Donald Pleasence. This is his big moment: he’s successfully blown James Bond’s cover. It certainly took long enough – we’re about ninety minutes into the film – but perhaps it’s understandable, because Bond has a new face too. For the first time in the series’ history, the role of 007 has passed from one actor to another: the irreplaceable Sean Connery has been replaced, and Australian George Lazenby – a former car salesman who had turned to modeling and starring in TV commercials – won the desperately-sought role by simply having the right look. Albert R. Broccoli, Harry Saltzman, and director Peter Hunt – promoted from supervising editor on prior Bond pictures to his own role-of-a-lifetime – were nervous about the change. The first half hour of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969) makes every sweaty effort to convince you that even though Lazenby’s new, he’s your James Bond. We first see him in fragments: the back of his head, a hand drawing a cigarette, his chin and mouth as it comes to his lips. We only see him in full when he emerges from his car to save a woman who’s attempting to drown herself in the ocean, but even then it’s only a brief glimpse. Hunt edits ferociously, never letting the eyes settle for too long. He delivers his big line to the camera, “I’m Bond, James Bond.” Then Hunt lets a fistfight break out between Bond and some stock thugs. The girl gets away, and Lazenby says to the camera – candidly – “This never happened to the other fellow.” A cute joke, though it makes zero sense outside of our knowledge that there used to be this guy named Sean Connery. But even then, the overeager reassurances don’t stop. The opening credits show clips from each of the previous Bond adventures. Then Bond goes to play baccarat in a scene reminiscent of Dr. No (and the novel Casino Royale). Later, after he attempts to resign from the British Secret Service, he empties his desk of props from Dr. No (Honey Ryder’s knife belt), From Russia with Love (the watch with retractable piano wire), and Thunderball (the rebreather). A janitor whistles a few bars from Goldfinger. It’s not until he begins to fall in love with Diana Rigg’s Theresa “Tracy” Draco DiVincenzo, with an uncharacteristically romantic love song (Louis Armstrong) on the soundtrack, that we begin to realize that this is a very different Bond, and a very different Bond film. No apologies are necessary.

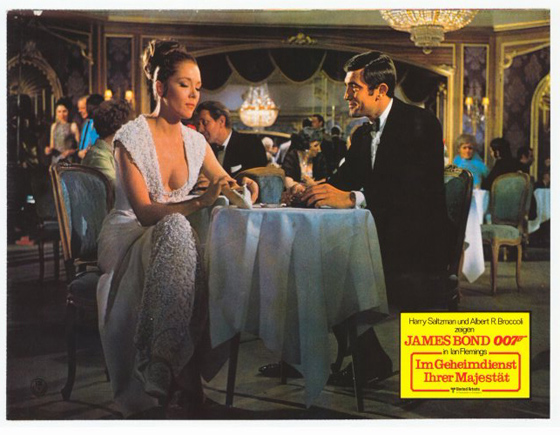

Tracy (Diana Rigg) keeps seducer James Bond (George Lazenby) at a safe distance.

There’s an earlier hint that this will be something special, and it’s not Lazenby’s comment about “the other fellow.” It’s in those Maurice Binder credits. For the first time since From Russia with Love, the theme plays without lyrics: no brassy Shirley Bassey, no swaggering Tom Jones. John Barry, who was previously trying to foist his own Bond theme song (called “007”) upon us when we were already pleased as punch with the Monty Norman one, now provides a substitute which is downright terrific. Lyrics would ruin it, and the filmmakers know it. “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service” is a thrilling instrumental, a driving piece to match the film’s downhill skiing action, but which also captures the feel of a doomsday clock ticking down, which is why Binder’s hourglass imagery is so perfectly matched to the piece. The credits tell us that yes, this is the same Bond as before, but it also tells us that time is running out for 007. This time, it’s not just the world that’s at stake – someone close to Bond is going to die. (Also, there are silhouettes of naked women. Binder’s brand of eroticism is strictly rooted in sleazy pulp paperbacks.)

Piz Gloria, Blofeld's isolated lair in the Swiss Alps.

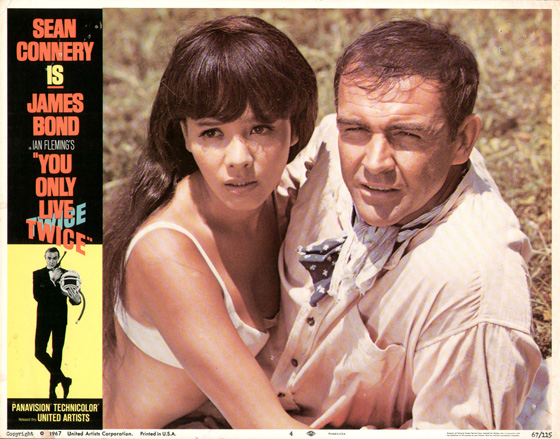

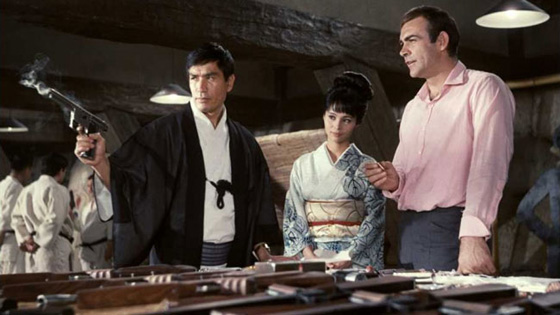

Ian Fleming’s novel was one of his best, and screamed for an adaptation. Broccoli and Saltzman’s EON Productions had been trying to get this film made for years, but the stars never aligned. The resolution of the lawsuit from Kevin McClory led to a hasty alliance and Thunderball, scuppering OHMSS. After Thunderball was complete, attention turned once more to the property, but Switzerland was having an unseasonably warm winter that year, and You Only Live Twice (1967) was made instead. The choice was unfortunate because that novel takes place after OHMSS, and chronicles Bond’s vendetta against Blofeld following the events in that book. By filming the climax of the Blofeld saga first, the plot to OHMSS effectively makes no sense. Why doesn’t Blofeld recognize undercover agent Bond? They just fought each other in a volcano! It was memorable! The answer seems to be that this is a reboot – new actors, new relaunch to the series – which makes all the desperate connections to previous films not just unnecessary, but extra-confusing. (Something just occurred to me. Bond never takes a prop from You Only Live Twice out of his desk. Maybe this is a prequel to that film? No. No it is not.) Peter Hunt, whose white-knuckle editing made the Orient Express battle between Bond and Red Grant in From Russia with Love one of the most exciting duels in cinema history, decided with his first director’s gig that he’d return to Fleming. This ebb and flow periodically occurs over the decades: the films get more extravagant and spectacle-driven, then make a conscientious return to the taut espionage work of the novels. (Incidentally, anyone who’s read the books knows that Fleming wasn’t all Timothy Dalton grim all the time. He was quite capable of over-the-top pulp too. The film of You Only Live Twice, with its volcano HQ and spaceships eating other spaceships, may be nothing like the book, but the source material – featuring a climax in a Japanese castle surrounded by the world’s most lethal plants, and Blofeld strutting about in a suit of armor – is plenty weird and campy on its own.) Hunt’s OHMSS is almost scrupulously faithful. Dialogue is frequently taken straight out of the novel. It has a From Russia with Love feel. It’s undoubtedly Fleming.

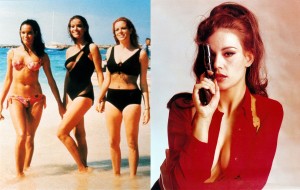

Two of the film's many Bond girls: Jenny Hanley as "the Irish girl" poses at Piz Gloria; Diana Rigg as Tracy prepares to shoot close-ups during the skiing/avalanche sequence.

The first quarter of the film sets up a deal between Bond and Tracy’s father, Marc-Ange Draco (Gabriele Ferzetti, Once Upon a Time in the West), the charming head of a crime syndicate who might remind the audience of the late great Pedro Armendáriz in From Russia with Love. Draco has watched Bond have a therapeutic effect upon the depressed Tracy, and suggests that if Bond marries his daughter, he will provide a critical lead on the case of Ernst Stavro Blofeld. Bond has barely entertained the idea when Tracy catches wind of the proposal and shoots it down. She urges her father to give Bond the information he needs, and he does – but the tough, cynical Tracy falls for Bond anyway. We’re about forty minutes into the film and Bond finally begins his investigation; one can be forgiven for forgetting this is a Bond picture. After discovering that the vain Blofeld is trying to prove he is a descendant of the de Bleuchamp line of earlobe-free nobles (he’s even had his earlobes removed), Bond goes undercover as Sir Hilary Bray, a representative of the London College of Arms, and under this pretense gains admittance to Blofeld’s remote Alpine hideaway, Piz Gloria, located on a mountain peak, and whose only access points are by cable car or helicopter. A bobsled run snakes down the steep slope, and armed gunmen lurk everywhere. Occasionally, beautiful women come out and do some curling. Piz Gloria – designed by Syd Cain (Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451, Ken Russell’s Billion Dollar Brain) in the absence of Ken Adam – is a fantastic location, one that was actually constructed by the Bond team, and which you can still visit today. There’s something unique about seeing the actors performing in front of windows that look out over the mountains; Hunt is able to maintain a high-altitude verisimilitude throughout the film. For some reason or another, the decision was made to set the film at Christmastime: references are made throughout, and a Christmas tree decorates the Piz Gloria interior. This is the one Bond film that’s ideal as holiday programming, and perfect to watch while snowed-in.

Telly Savalas as Blofeld.

The international collection of young women are part of an experimental allergy therapy run by Blofeld, and their ranks include Angela Scoular (1967’s Casino Royale), Joanna Lumley (Absolutely Fabulous, The Satanic Rites of Dracula), Catherine Schell (Moon Zero Two), Julie Ege (Creatures the World Forgot), Anouska Hempel (Scars of Dracula, Black Snake), Jenny Hanley (Scars of Dracula), Sally “Dani” Sheridan (The Sorcerers), and others. It’s implied that Bond sleeps with a great many of them. All goes swimmingly until one of his seductions is interrupted by a literally-undercover Irma Blunt (German actress Ilse Steppat, who sadly died the year this was released), Blofeld’s henchwoman. A downhill ski chase shortly follows, one so exciting that it formed the template for every similar stunt sequence in later Bond films. At one point, Bond is reduced to skiing on one ski. He also sends an enemy plummeting off a cliff, and Hunt brutally holds the camera until we can see the body meet its shadow at the distant, snowy bottom. The chase continues as he reunites with Tracy, ice skating with other tourists, and she takes the wheel for a car chase that includes a few laps in a demolition derby. Her bravery (and ace winter driving skills) proves she’s the woman for Bond, and before the night is out he’s proposing marriage.

Tracy and James have a chilly meet-cute in a casino.

The last third of the film is about as perfect as anything that’s ever emerged from the Bond series. When Tracy is kidnapped by Blofeld, and M (Bernard Lee, as great as usual) gives Bond a cold shoulder, Bond is forced to turn to Draco and his syndicate for an armed raid on Piz Gloria. Helicopters approach through the Alps while Barry’s theme ticks down the clock. Rigg and Savalas recite poetry while circling each other, plotting their moves. Lazenby throws himself down the icy path from the heliport, sliding across his belly while firing his machine gun, and Barry finally gives the audience Monty Norman’s Bond theme. (For the last couple of films, the theme is reserved for a “big moment.” It’s geared toward getting the audience to applaud, but not overused.) Following the destruction of Piz Gloria, we witness the impossible: James Bond’s wedding. Bond throws Moneypenny (Lois Maxwell) his hat one last time, and the newlyweds drive off. If only they didn’t stop to pull the flowers off the car… For all the gripes about Lazenby over the years, he sells the final scene. He was a novice actor, but he proves he could have been a substantial Bond if given the chance. The final moment of the film is heartbreaking, and we don’t see anything like it again in the series until Bond meets Vesper Lynd in Casino Royale (2006). Last month Steven Soderbergh wrote about his love of OHMSS, arguing that it’s the best film in the series. About Lazenby, he wrote:

I actually like him—a lot—and think he could have made a terrific Bond had he continued…What seems obvious to me, though, is no one was helping him during the shoot or the edit (they won’t even let him finish a fucking sentence onscreen). It feels like everyone was so focused on what he wasn’t (Sean Connery) that they didn’t take the time to figure out what he was (a cool-looking dude with genuine presence and great physicality). For instance, they should have known that a lot of the one-liners that would have worked with Connery don’t work with Lazenby. This isn’t because he’s bad, it’s because his entire affect is different, less glib. This, to me, is a lack of sensitivity and understanding on the part of the filmmakers and not a shortcoming of the lead actor, because Lazenby has one thing you can’t fake, which is a certain kind of gravitas. Despite this, there is no attempt to bring it out or amplify it, which is a huge missed opportunity. Also, Lazenby has a vulnerability that Connery never had—there are scenes in which he looks legitimately terrified and others in which he convinces us that he is in love with Tracy (particularly in the final scene).

It’s an interesting observation, coming as it does from a director who, in Haywire (2011), also worked with an actor with “great physicality” and limited acting experience (Gina Carano); I don’t think I’ve heard anyone make his particular argument before – that Lazenby simply wasn’t used as well as he could have been. In the documentary “Inside On Her Majesty’s Secret Service,” Lazenby regrets his early departure from the series; he claims that at the time he didn’t think the character would stick around past the 60’s. If he hadn’t quit, it’s not certain he would have returned anyway: although the same documentary acknowledges that many of the stories of discontent on the set were exaggerated by the press, there were genuine, unfortunate incidents instigated by Lazenby too, the result, perhaps, of youthful arrogance. But most damningly, the film underperformed compared to previous Bond pictures. This would lead to another overture from EON to Connery to help put the series back on track, and Diamonds are Forever (1971) was the result.

The wedding of Mr. and Mrs. James Bond.

Paradoxically, OHMSS is nonetheless one of the high water-marks of the series. Fans will forever wonder what the film would have been like with Connery attending Bond’s wedding, but on this most recent viewing I realized that it is this particular film, flaws and all, that I love. The Christmas theme and the snowy locations, which capture a real sense of slippery roads, drifting snow, freezing cold, and perilous winter elements; the contrast with the crackling fireplace inside Piz Gloria, the Christmas tree, the buxom girls unwrapping their deadly presents from Blofeld or stroking Bond’s thigh while asking him what bezants are; the downhill chases in all their permutations; John Barry’s music and how it suits Diana Rigg’s porcelain face and Mona Lisa smile. I just can’t extract Lazenby from the scenario anymore. Even a remake with Daniel Craig – which I hope happens, whether or not anyone’s discussing it – will somehow disappoint me because it’s not this 1969 film. This Bond “flop” is a classic.