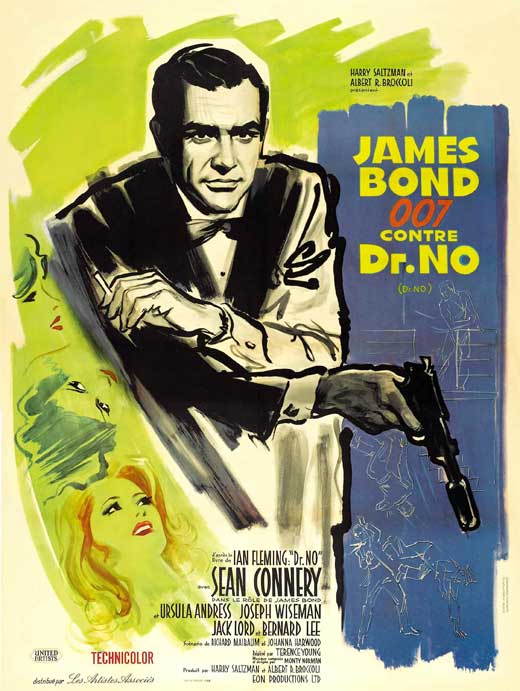

One of the main pleasures of watching Dr. No (1962) now is observing the formative steps of what will become the most popular and widely imitated film series of all time; it’s watching the iconic in its nascent stage. In many ways, there’s a similar thrill offered in Casino Royale (2006) and Skyfall (2012), that of watching the pieces of the “James Bond movie” come together, but theirs is by necessity self-conscious, nostalgic. When Miss Moneypenny finally arrives in Skyfall, seated behind that desk as James is summoned to meet M. through an adjacent door, we smile because these seemingly trivial elements are important to us. Although producers Harry Saltzman and Albert R. Broccoli intended their debut 007 picture to be a smash, even they couldn’t have predicted how lucrative and enduring the franchise would become. That’s why there’s still some charm and excitement in seeing the gun-barrel logo opening the picture, filling the screen with blood, before the “James Bond Theme” blasts at us. They were trying something different; they couldn’t know with certainty that this would work. Moneypenny is played by a hard-working British actress (the wonderful Lois Maxwell) seated behind a desk, flirting with Bond in a brief, charming little scene; there is no reason to find her presence significant. There are no real gadgets, no Q., and the story is limited to only one scenic locale – though we can attribute our own significance to it, since we know it’s the place where Ian Fleming lived and wrote all the James Bond novels: Jamaica.

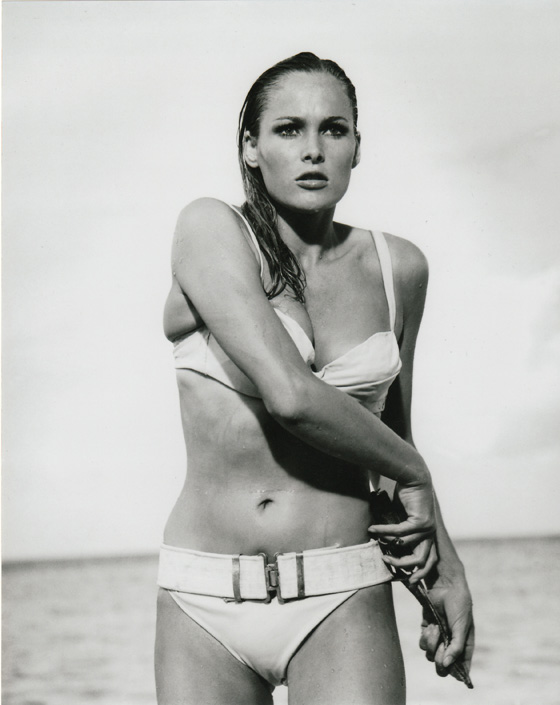

Ursula Andress as Honey Ryder.

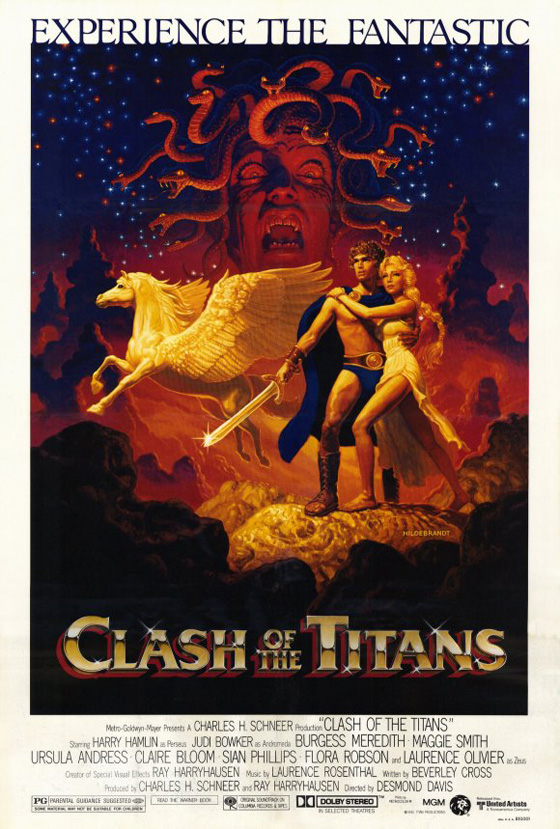

But Saltzman (a Canadian) and Broccoli (a native of Queens, New York) were fans of Fleming’s popular novels, and intended to elevate Dr. No above the typical low-budget British spy thriller: they wanted it to be the spectacular first entry of a series. (Cary Grant was considered for the lead, but it was assumed he’d never come back for a sequel.) Shooting in color and on location in the place where the novel was set was the first significant step toward separating Dr. No from its contemporaries. The film gained an exotic, even erotic charge from the clear blue sea and white Jamaican beaches. Jamaica was one of the film’s greatest special effects; the other was Swiss model and actress Ursula Andress. Arriving with her husband, photographer John Derek (as well as, incidentally, Bunny Yeager, who shot some of the most famous Bettie Page photos), the young, statuesque beauty embodied what would become the Bond Girl: a little-known model or beauty queen, preferably European, who looks great in a swimsuit. And like so many of the early Bond girls, her voice would be dubbed. The chosen director, Terence Young, would do much for establishing the detached cool of James Bond, and would go on to direct the second Bond installment and one of the most satisfying of the entire series, From Russia with Love (1963). The Bond villain is one of the most memorable of Fleming’s novels, living in an island fortress populated by uniformed, machine gun-toting guards; the half-German, half-Chinese Dr. No, with his deadly metal hands, would be played by Joseph Wiseman (Viva Zapata!) in a manner that would influence all series villains to come. His booming, disembodied voice as he intimidates his henchman, Professor Dent (Anthony Dawson, The Curse of the Werewolf), foreshadows Ernst Stavro Blofeld’s chilling tenor. Singer-turned-composer Monty Norman composed the “James Bond Theme” with an arrangement by composer John Barry, and it is this which plays over Maurice Binder’s stylish opening titles; unlike later films, there is no proper theme song, unless you count a calypso take (by Byron Lee & The Dragonaires) on “Three Blind Mice,” which during the credits takes over following some pounding drums and gyrating silhouettes. (The most prominent song in the film is “Under the Mango Tree” sung by Norman’s wife, Diana Coupland. If you are looking for a song-with-lyrics that’s most closely associated with Dr. No, then look no further. Honey Ryder sings it while looking at her seashells, and while Bond is “just looking.”) Norman and Barry’s theme music for 007 was so enjoyable, so addictive, so whistle-able, that editor Peter Hunt – another invaluable asset to the early films – happily applied thick globs of the theme everywhere. Bond enters a room: the Bond theme plays. Bond lights a cigarette: the Bond theme plays. In these Daniel Craig days of restraint, the theme is rationed out very carefully. Not so in the joyous time of Dr. No, when everything that clicked was treated as a marvelous discovery.

James Bond (Sean Connery) is tailed on his way to a rendezvous with the duplicitous Miss Taro.

Then there’s the matter of Sean Connery. He was not yet a recognizable star (one of his larger roles was in Disney’s Darby O’Gill and the Little People), and was chosen after a long search by the producers, who reportedly considered at various points Richard Johnson (The Haunting), Patrick McGoohan (Danger Man), and Roger Moore. It is Connery’s Bond, more than any other element, that holds Dr. No together and ensured the success of the franchise. As much as I enjoy Craig’s 007, anyone who claims he’s the best of the Bonds really must rewatch the first three films in the series to see how good, how natural Connery was in the role. Was he Fleming’s James Bond? Not quite, and perhaps Craig’s is closer on that score. Fleming’s Bond was more self-questioning, more weary of the job, more reluctant to kill in cold blood. Yet the best scene in Dr. No does not take place in Fleming’s novel. After placing Dr. No’s sexy spy, Miss Taro (Zena Marshall, Let’s Be Happy), under arrest – she’s escorted off in a taxi with a government official – Bond makes up the bed to look like someone’s sleeping in it, then waits behind the door, biding his time with a game of solitaire. He knows Taro was trying to delay him until one of No’s men could arrive, and soon the assassin emerges through the door, firing with a silencer at the bed. Bond disarms the man, revealing him to be Professor Dent. When Bond briefly lets his guard down, Dent seizes his gun and pulls the trigger. Nothing happens. “That’s a Smith & Wesson,” Bond says, unperturbed, a cigarette dangling from his lip, “and you’ve had your six.” He proceeds to shoot Dent; the man convulses violently in the air and lands on his face on the floor. Bond then shoots the inert figure in the back. It’s a cold, brutal scene, and perhaps – arguably – a step further than Fleming would have gone. As this comes just after we’ve watched Bond blatantly exploit Miss Taro, a treatment that causes her to spit in his face, we’re given a memorable introduction to the hard-boiled, envelope-pushing sex and violence that the initial Bond films would offer eager audiences of the 60’s. Connery’s Bond is certainly a chauvinist and a playboy, a man of an era that now seems like ancient history, but his charisma still holds. Dr. No is rather leisurely paced compared to later Bond entries, but you can’t take your eyes off Connery as he acts the detective (which is how he describes himself to Honey Ryder), following clues, evading assassins and double agents, determining who he can trust (John Kitzmiller’s Jamaican fisherman Quarrel, Jack Lord’s Felix Leiter) and who he can’t.

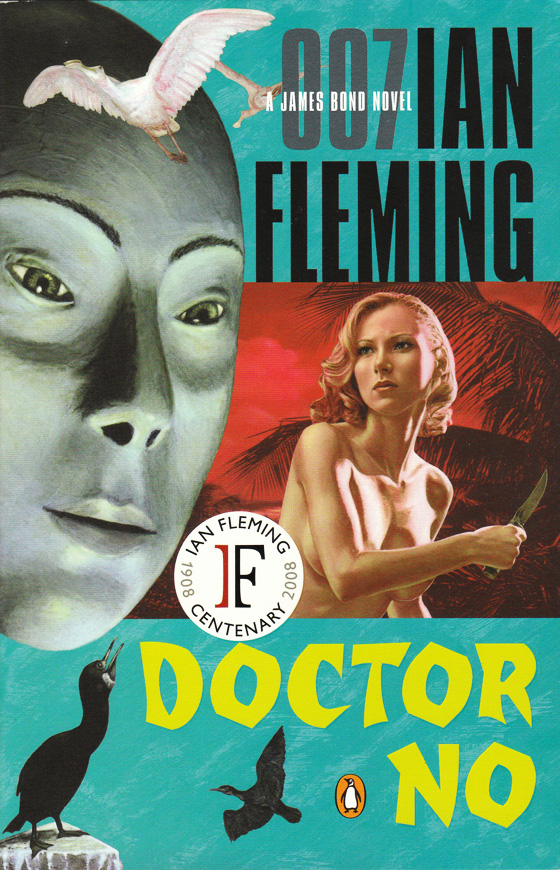

The novel, with cover art for the 2008 Ian Fleming Centenary edition by Richie Fahey.

Differences between Fleming’s Bond and that of the films bothers me less than some because although I enjoy the books, I don’t hold them up as timeless, unimpeachable works. Some are better than others; some are burdened too much by Fleming’s dated views on race and gender. (For the record, my favorite Bond novel is Moonraker, a book so darkly ironic that Bond doesn’t even get the girl.) But it would be wrong to describe Dr. No as unfaithful to its source material; to the contrary, Saltzman and Broccoli insisted the script (by Richard Maibaum, Johanna Harwood, and Berkely Mather) adhere as close as possible to Fleming. If anything, they’re required to pad the story out from the original text, since the novel Doctor No – published in 1958 and the sixth in the series – is unusually tight and simple, getting to No’s island headquarters pretty quickly for an extended showdown between hero and villain. All changes are largely done by necessity. Dr. No doesn’t retain a giant squid for Bond to battle, and he isn’t killed by being drowned in seabird guano (something that would have risked parody, though certainly the humor was intentional on Fleming’s part). An attempted murder of Bond with a centipede becomes a tarantula onscreen. An extended, agonizing crawl through a booby-trapped tunnel that Dr. No has created for Bond as an endurance test is simplified to the point of losing its original narrative purpose (Bond now simply crawls through a shaft and only risks scalding water). Young attempted to film a scene from the novel in which Honey Ryder is tied down and left to a squadron of sand-crabs, but the crabs arrived half-frozen or dead, and the scene was changed so the threat is death by drowning instead. Unlike in the novel, Doctor No here works for SPECTRE, the international criminal organization led by Blofeld, a character who won’t be introduced until the next film. But one of the more interesting examples of the film’s faithfulness is the famous scene of M. (Bernard Lee) replacing Bond’s Beretta .25 with a Walther PPK 7.65 mm, to Bond’s displeasure. M. mentions that the Beretta almost cost Bond his life in a previous mission. That mission was actually From Russia with Love, the novel which preceded Doctor No, and which ended with Bond’s apparent death by Rosa Klebb. Yet the film adaptation of From Russia with Love would come next, and act as a sequel in the film series continuity.

Joseph Wiseman as Dr. No.

Location shooting occurred not very far from Fleming’s Goldeneye home – the author paying frequent visits to the set – but interiors were filmed at Pinewood Studios, where production designer Ken Adam (Dr. Strangelove) sculpted Dr. No’s headquarters. The designs range from the ornate and intricate, such as No’s Captain Nemo-styled dining room (which contains a giant aquarium, a fireplace, natural rock and hardwood floors, and stolen works of art), to the deceptively simple, such as the chamber where No’s voice interrogates Dent, lit only by the round grate in the ceiling that creates a domed shape of light and shadow against the wall. This Modern Art production design is so indelible that it’s become permanently associated with 60’s superspies, and paid tribute to in the Austin Powers movies and The Incredibles (2004). Adam would continue to top himself in the Bond pictures, reaching his creative zenith in the elaborate spaces of The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) and his 007 swan song, Moonraker (1979). You see his sets and you want to walk around them, live inside them. The film ends, as Bond films must, with the fiery destruction of the enemy base, and it’s only in the climactic battle – Bond and Dr. No wrestle in radiation suits – that the film stumbles a bit; the size of Adam’s set notwithstanding, Young needed to apply a slightly more creative touch to enliven the climax. (Maybe we did need the squid and the guano.) But by this point, Dr. No has already distinguished itself from stock B-pictures. It had provided an ideal template, and its worldwide success would allow Saltzman and Broccoli the opportunity to refine, improve, excel. That path started on a Jamaican beach underneath the mango tree, and would continue with a nail-biting trip out of Istanbul on the Orient Express.