On Friday night Masaki Kobayashi’s classic anthology of Japanese ghost stories, Kwaidan (Kaidan, 1964), kicked off the month-long series “International Horror Classics” at Madison, Wisconsin’s Cinematheque. It’s hard to pass up the opportunity to see this film projected in lustrous (and, yes, occasionally scratchy) 35mm – such a rarity these days that even the purist Cinematheque is being forced to raise funds for a digital projector and server to accommodate DCP (Digital Cinema Package) screenings, now that studios prefer DCP over shipping actual film prints to revival theaters. On the big screen (or, at least, as big as the Cinematheque provides), Kobayashi’s film immerses the audience in its sweeping brushstrokes of red, orange, purple, blue, and black. Lost in a dark theater and free of distractions, the meticulously-paced, dream-like film is somehow both hypnotic and electric. Not that there weren’t plenty of walkouts (and one audible, persistent snore) from those who couldn’t fall in line with Kwaidan‘s peculiar rhythms, or were intimidated by its 161-minute running time. Few were complaining that this wasn’t the original, 182-minute cut of the film (which only in recent years has been made available to English-speaking audiences via Eureka’s Masters of Cinema U.K. DVD); anyway, I presume this was the only 35mm print the Cinematheque could acquire, marked with a red “Special Jury Prize – Cannes Film Festival 1965” notice at the front.

A warrior rises from the grave in "Kwaidan"'s segment "Hoichi the Earless."

The film is based upon the stories of the Irish author Lafcadio Hearn, who at the age of 40 relocated to Japan and published books of Japanese folklore and culture under the name Koizumi Yakumo. Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things (1904) is his collection of “kaidan,” or Japanese ghost stories, some of which he translated from old texts, others having been told to him. The film adaptation came from Toho Studios in full color and with an epic running time, dazzling visuals and set design, and a prestige director at the peak of his craft: Masaki Kobayashi had previously directed the three-part, nine-and-a-half-hour-long WWII drama The Human Condition (1959), as well as the samurai film Harakiri (1962), another Cannes Special Jury Prize winner. Kwaidan would present four separate ghost stories, each framed in an historical context and often explicitly referencing the craft of art and storytelling. Staged almost entirely inside a cavernous airplane hangar, decorated and lit to transform itself into a multitude of fantastic environments, the film flaunts its artificiality, drawing connections to kabuki theater, but also casting the audience’s attention toward the art of moviemaking. We’re conscious of when a spotlight suddenly outlines a distraught, lonely man, or lights up a fallen – and possibly haunted – bowl lying upon the floor. We’re made aware of the presence of makeup, which becomes highly stylized whenever unearthly elements are introduced. Frequently the soundtrack is displaced by Tôru Takemitsu’s chilling, jarring score, which combines traditional Japanese music with the blatantly avant-garde. It’s bold of a filmmaker to draw this much attention to himself, and yet, if you open yourself to it, you can easily drawn into the film’s ghostly spell.

Rentaro Mikuni, in his horror, physically transforms in "The Black Hair."

The film’s first segment, “The Black Hair” (“Kurokami”) is the tale of a samurai (Rentarô Mikuni, The Burmese Harp) and his wife (Michiyo Aratama, The Human Condition) living in poverty; at the outset, he abandons her, declaring that “career is important to a man,” and refusing to waste away all his years destitute. He finds his way into wealth, but not happiness, when he marries a vain and vindictive woman (Misako Watanabe, Youth of the Beast) of a wealthy family. Realizing the error of his ways, he returns to his first wife, and finds her just as he left her. Of course, not all is as it seems, as signaled by his wife’s statement “I’ve forgotten my sorrow”; in the morning, her long, lovely black hair hides the face of a dessicated corpse lying beside him. The husband finds himself cursed and disfigured by ugliness (and baldness). The story has some structural similarity to Kenji Mizoguchi’s famous film Ugetsu Monogatari (1953), itself taken from an 18th century anthology of folk tales bearing the same name. What separates “The Black Hair” is the aforementioned theatrical style. When the supernatural finally unfolds, traditional cinematic continuity falls to the wayside. The husband’s face transforms dramatically from one shot to the next. The house decays and crumbles. The score pounds and clangs and screeches. Still, this proves to be the most conventional of the film’s episodes.

Lips in the sky: the sensual world of "The Woman of the Snow."

More interesting is “The Woman of the Snow” (“Yuki-Onna”), starring Tatsuya Nakadai (of The Human Condition and many Kurosawa films) as a woodsman who encounters a wraith of the winter (Keiko Kishi, Rififi in Tokyo) who happens to be eerily beautiful. He catches her killing his friend Jack Frost-style – with her cold breath. She’s about to freeze him to death, too, but changes her mind out of sympathy (and perhaps love-at-first-sight). She makes him promise to never tell what he has seen; if he breaks it, she will come to him and kill him. This familiar ghost-story setup gets a twist which is genuinely haunting, because it involves matters of the heart. If that doesn’t stick with you – and it ought to – then you’ll at least remember the set design. Kobayashi’s set shifts with the seasons, and the backdrop eschews realistic Hollywood matte paintings, opting instead for artwork that’s deliberately surrealistic. Which means that you will be aware that the actors are performing in front of a painted wall, but what a setting to inhabit: eyeballs stare accusingly at the actors during the rage of a winter’s storm; the sun bursts through the clouds in fractured squares; a meet-cute between the woodsman and a traveling girl gains an added layer of sensuality with the streaks of red lips and lipstick in the sky behind them. In one dissolve, Kobayashi even merges the actress’s lips into those red streaks, seeming to transform her corporeal self into a sky-spirit.

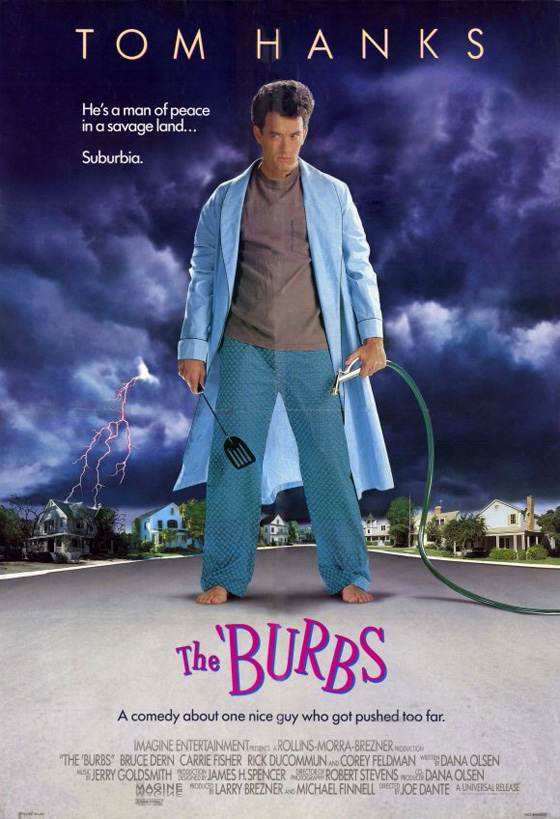

Warring clans prepare for a conflict at sea in "Hoichi the Earless."

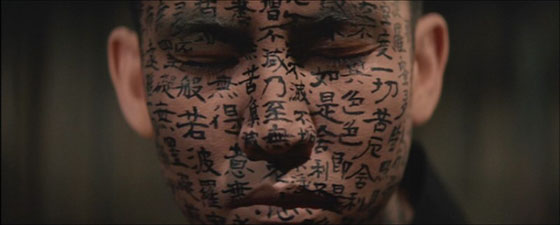

The film’s strongest – and longest – story, “Hoichi the Earless” (“Miminashi Hôichi no hanashi”), is appealing on many levels: as a sophisticated, macabre variation on a traditional fairy story (as my wife pointed out, you can easily replace “empty cemetery by the shore” with “underground fairy kingdom” to trace the similarity with traditional European folk tales); as a grisly horror tale; and as a visually stunning fusion of disparate cinematic styles. To that latter point, the story begins with another surreal setpiece, as two warring clans – the Genji and the Heike – battle on flimsy wooden boats upon a (stage-bound) sea. After the defeated Heike warriors, along with their infant emperor, decide to commit suicide by drowning, and we flash-forward in time, the style becomes more realistic, the visual palette cooler, laying the framework for another supernatural intrusion into ordinary life. In a rainswept Buddhist temple, the blind Hoichi (Katsuo Nakamura, Pleasures of the Flesh) serves the head priest (Takashi Shimura of Ikiru and Throne of Blood) and entertains him by playing the biwa. His music draws the attention of the dead warriors lurking in the sea, and they summon him out to the cliffs, where, night after night, he plays for the infant emperor and the fallen from both clans, singing their favorite song: the one that describes their battle. An extraordinary extended sequence shows the set changing around the blind, unwitting Hoichi while he performs, and first the Heike, then the Genji dead look on with heartrending sadness. When two comic-relief servants of the temple follow Hoichi and discover him playing among dancing spirit-lights, they pull him away and declare his transgression to the priest. The priest tells Hoichi that if he continues to dwell among the dead, he will soon join them permanently; to protect him from the next summoning, they paint his body from head to toe with protective writing and symbols; and at night, he is left alone in the temple to confront the spirit of the soldier who calls for him.

An undefeated warrior (Kanemon Nakamura) encounters a ghostly face "In a Cup of Tea."

The final segment, “In a Cup of Tea” (“Chawan no naka”), is the shortest, and notable in that it connects Kwaidan with the metaphysical storytelling terrain of The Saragossa Manuscript (1965), as well as the framed stories of Pasolini’s “Trilogy of Life” (1971-1974). We meet the author of our stories, who decides to tell an ancient piece of folklore left unfinished by its writer. We’ve been warned there’s no ending to the tale, but, in Kobayashi’s masterstroke, the conclusion we’re given leads the film to (almost literally) swallow itself whole. It’s a clever knot to tie up one of the enduring classics of Japanese cinema – a film that is both overtly theatrical and painfully intimate, absurdly stylized and delicately human. Kwaidan unfolds like a three-hour dream.

Upcoming films in the Cinematheque’s excitingly varied series include Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (1960), Hammer’s The Curse of the Werewolf (1961), and Lucio Fulci’s The Beyond (1981), in addition to a benefit screening (on behalf of the UW Cinematheque’s quest for a new digital projector) of Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979) at Sundance Cinemas in Madison on October 29.