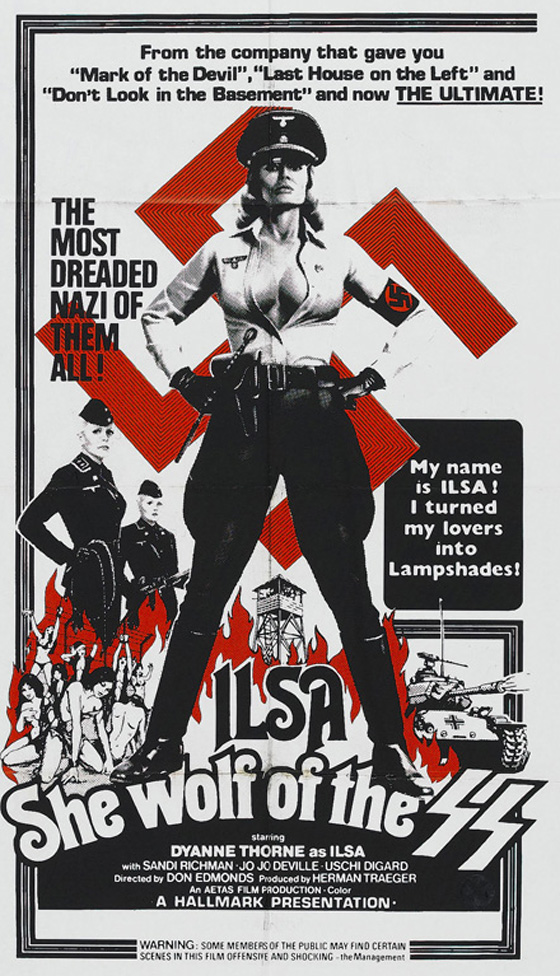

Sometimes a movie owes you a “safe word” up-front. Such a film is Ilsa: She Wolf of the SS (1975), the notorious Nazisploitation film that ups the sleazy ante from previous entries in the genre such as Lee Frost’s Love Camp 7 (1969), as well as the various women-in-prison films that were popular throughout the 70’s. With its increasingly extreme (and absurd) torture sequences, Ilsa aims to get patrons into seats through word-of-mouth: the poster promised, “A Different Kind of X.” It’s the sort of movie that mercenary commercialism produces, playing to the basest instincts of the audience. You think your imagination is sick? We’ll show you something even worse, and you’ll pay us for the privilege. This was the trend of the decade as far as grindhouses were concerned: more extreme measures were necessary to jolt the jaded audience, and Ilsa could show the way. It all sprung from the mind of producer David F. Friedman (Blood Feast, Love Camp 7), who is here so confident of his product that he uses a pseudonym, “Herman Traeger.” It’s not Friedman, but Herman Traeger who signs the Nazi-red title card that claims: “The film you are about to see is based upon documented fact…Because of its shocking subject matter, this film is restricted to adult audiences only. We dedicate this film with the hope that these heinous crimes will never occur again.” Here’s exploitation in a nutshell. We completely condemn this! Now let’s watch.

Ilsa (Dyanne Thorne) prepares her prisoners for her medical research.

All of my “grand guignol” arguments in defense of some of the more extreme entries in this month’s grindhouse marathon fall apart when it comes to Ilsa: She Wolf of the SS, simply due to the obvious bad taste of the enterprise. Not that I feel any desire to defend it. (Perhaps I should also take on a pseudonym, switch on the projector, and flee the city limits.) Ilsa is the kind of movie that was inevitable, a crossing of the invisible line that was drawn by Holocaust films and commentators. Although it’s not the ultimate in sleaze – cinema hadn’t plumbed the bottom of tastelessness yet, and probably still hasn’t (sorry, human centipedes and Serbian films) – it’s significant in that it declares that nothing is off-limits, not even turning a concentration camp into a grisly arena of debauchery. Of course, in spite of the hilariously inadequate disclaimer that this is based on historical fact (Ilsa is inspired by the “Bitch of Buchenwald,” war criminal Ilse Koch), it is in fact an S&M fantasy with a Hogan’s Heroes backdrop. I mean that literally: this X-rated movie was shot on the set of Hogan’s Heroes. Ilsa is the ultimate dominatrix, and the film’s central twist – that she secretly desires to be dominated, preferably by an Aryan superman – just cements the film’s status as a dark fable for those with a very specific fetish, one that prefers busty women in tight-fitting uniforms exacting excruciating punishments. (Somewhat unintentionally, A Month at the Grindhouse, which started with the “Olga” movies, comes full circle with S&M fantasies that read like indecipherable code to this author. But it’s clear that Ilsa is Olga reincarnate and more sadistic than ever.) Bill Landis and Michelle Clifford’s 2002 book Sleazoid Express frequently betrays the authors’ predilection for S&M images; they write, “There’s a built-in apprehension factor inherent in viewing Ilsa: When would the sadism cease being erotic and start sickening the viewer?” Which tells me: apparently some of this is erotic.

Ilsa accepts a bondage scenario from her lover, the prisoner Wolfe (Gregory Knoph).

What takes up much of the film’s 90 minutes is Ilsa conducting “medical experiments” on her female prisoners, testing her theory that a woman has a greater threshold for pain than a man. She – deep breath – twists off a girl’s toes, administers static shocks from a dildo (and later through wires attached to a woman’s erogenous zones, including the use of nipple clamps), slices open wounds for the application of “gangrene pus” and maggots carrying typhus, boils one woman alive, puts one’s head in a vise, and places another (sexploitation icon Uschi Digart, in a cameo) in a pressure chamber. To celebrate the arrival of “The General” (Richard Kennedy, The Witch Who Came From the Sea), Ilsa has one naked girl placed in a hangman’s noose, her feet balanced on a block of ice set upon the banquet table; as the dinner proceeds and the ice melts, she’s slowly throttled by the noose. Ilsa, who has a voracious sexual appetite, is disappointed that the General only prefers to be dominated (he declares her a “blonde goddess” and asks her to urinate on him, which she does, frowning). She is accustomed to sleeping with the male prisoners; in the film’s opening sex scene, she demands her partner’s patience so that she might achieve her own sexual satisfaction. When he finishes early, she sighs, “You should have vaited.” But he could not vait, so in the morning she has him castrated, her typical post-coital treatment. Only blond, blue-eyed Wolfe (Gregory Knoph) meets her Aryan ideal. He explains to a fellow prisoner that he is blessed with the ability to maintain an erection, without orgasm, for as long as needed; he describes himself as a “machine.” Ilsa is delighted at his stamina, and soon becomes his slave, which fits perfectly with his plan to liberate the camp. The finale is a peculiar combination of The Great Escape-type WWII films and over-the-top 70’s horror, with the disfigured victims of Ilsa’s experiments overcoming the guards and exacting their revenge.

Ilsa, on her quest to scientifically prove that a woman can tolerate extraordinary pain.

Even more peculiar than Ilsa‘s existence is the fact that the film was a big enough hit to spawn sequels and rip-offs. Though Ilsa meets a definite end (ironically, at the hands of an SS officer and not one of her victims), the film’s director, Don Edmonds, brought her back in Ilsa, Harem Keeper of the Oil Sheiks (1976). Her final outing was Ilsa, the Tigress of Siberia (1977, directed by Jean LaFleur), though Thorne played a similar character in Jess Franco’s Wanda, the Wicked Warden (1977), a film that has also been released under the title Ilsa, the Wicked Warden, to cash in on her character’s popularity. Other films in the Nazisploitation genre to ride the coattails of Ilsa‘s success include Deported Women of the SS Special Section (1976), SS Experiment Love Camp (1976), and Last Orgy of the Third Reich (1977). The thing about Ilsa: She Wolf of the SS is that it’s a slickly-made film, far more polished than the films Friedman made with Herschell Gordon Lewis. With decent production values, believable makeup effects, and adequate acting (though the accents are all over the place), the over-the-top, X-rated sadism on display is all the more jarring. Ilsa’s stated experiment of testing the limits of the pain threshold can be extended to the film itself: Friedman and Edmonds are seeing just how much an audience can take while still demanding more (the follow-up films are reportedly even more graphic).

Wolfe leads a prison break.

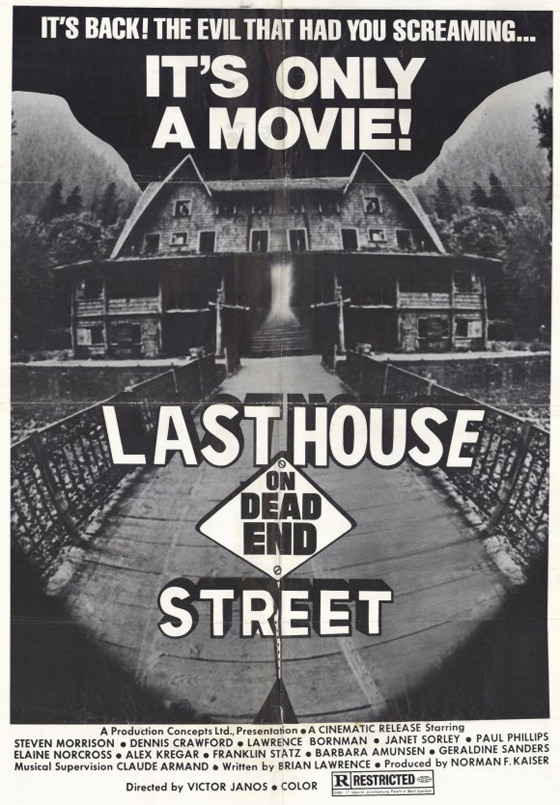

In certain ways, the grindhouse films of the 70’s were a grand experiment in exploding taboos and every measure of decency: show me more, show me more, I can take it. But that hunger for cinematic catharsis would begin to wear off. The oft-noted sea-change initiated by Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977) – the rise of the mainstream, audience-crossing blockbusters – began to push transgressive exploitation cinema even further to the margins. Once upon a time in the 70’s, larger audiences wanted their minds blown with new extremes of sex and violence. As the 80’s arrived and wore on – and while 42nd street was slowly sanitized – exploitation started to become as predictably packaged as a Happy Meal. Jason slashed up naked females on a union schedule and for union wages; Freddy made wisecracks and left room for cameos by Dick Cavett and Zsa Zsa Gabor. The stuff that really felt dangerous became harder to find; you’d need the tenacity of a fetishist. The home video revolution helped keep fever-dream memories of the likes of Ilsa and Olga alive, particularly in the DVD boom years of the early 21st century; and now, with a fractured audience driven by their unique, specific interests – not to mention the cheaper costs of producing one’s own movie – there’s more room for esoteric and original entertainment to thrive. But we don’t need to carve up bodies in newer and more nauseating ways. We just need to break loose of the Hollywood rails. We need to be original…dangerous. That’s what the filthy screens and sticky floors of the 42nd Street movie houses should really teach us.

Still, sometimes you should establish a “safe word.”

This is the last entry in A Month at the Grindhouse. I’ve set up a permanent page collecting all the essays here.