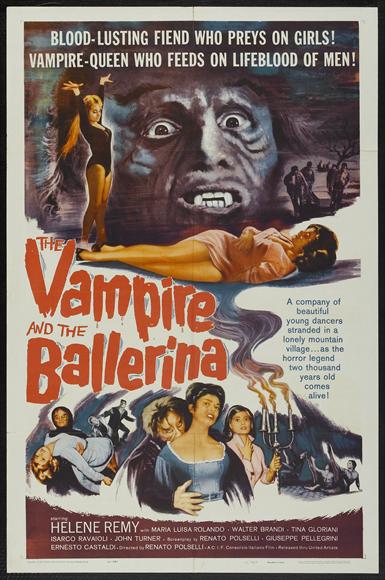

Watching the interviews and reading the essays included in Arrow Video’s new deluxe Blu-ray edition of Mike Hodges’ Flash Gordon (1980), I’m struck at how poorly received the film was on release. At the time, I was too young to be aware of critical reactions, but I embraced the film well enough; there were, after all, rocket-ships and aliens and clearly defined roles for the good guys and the bad. I was also too young to understand the concepts of camp or irony, the abundance of which in Flash Gordon having apparently left such a bad taste for many viewers. The film has earned a stronger reputation over time, in part, I think, because it’s so different from more fashionable modes of fantasy or comic book filmmaking. There’s nothing gritty or realistic to be found here. Star Wars, the film whose success allowed Flash Gordon to happen, went to great lengths to make its fantasy world feel lived-in and convincing; modern superhero films make a point of showing how their comic book counterparts might arise organically from our contemporary setting, Iron Man suits and all. Producer Dino De Laurentiis, hot off his King Kong remake, couldn’t conceive of Flash Gordon being a straight-faced film; the most compelling supplement on the disc is its look at what might have been, had original director Nicolas Roeg (The Man Who Fell to Earth) and writer Michael Allin (Enter the Dragon) been allowed to pursue their much more serious adaptation of the Alex Raymond comic strip. Instead, De Laurentiis, who had originally envisioned this as a Fellini spectacle, commissioned a rewrite from Lorenzo Semple Jr., writer of the Batman TV series, and replaced Roeg with Mike Hodges, the Get Carter (1971) director who didn’t have much interest in science fiction or superheroes. Queen provides the soundtrack, including its immortal title track. A football player with no acting experience, Sam J. Jones, plays the lead. All tongues are firmly lodged in their respective cheeks. In retrospect, it may actually be that Roeg would have made the more commercial film. De Laurentiis, with visions of Fellini still swirling in his brain, produced a pop artifact so delirious and outré that it couldn’t connect with most critics and audiences of 1980. Wrong movie, wrong moment. But nowadays, if you’re going to sit down to watch Flash Gordon, you don’t want anything remotely realistic. You want gold lamé costumes, an amazing cast delivering ridiculous dialogue, a PG-pushing fixation on sex and bondage, eye-popping sets, chintzy bluescreen, and Freddie Mercury wailing about Flash saving every one of us.

Ming the Merciless (Max von Sydow) and his mysterious henchman Klytus (Peter Wyngarde).

So my appreciation for this movie, which I hadn’t sat down to watch for ages, has evolved. As a kid, I only cared that it provided nonstop imagination fuel for my still-developing brain. As a young adult, I found the comedy – in particular, that impromptu football game in Ming’s court – too much to stomach. And now it feels like the follow-up to Barbarella and The Rocky Horror Picture Show that I didn’t know I needed back in my life. (Rocky Horror‘s Richard O’Brien has a role as a pipe-playing member of the Arborian Treemen, as though to give the film his “future midnight movie” stamp of approval.) Alluringly, all the shots of the skies are optical effects in the style of psychedelic-60’s liquid light shows, giving everything a cosmic, lysergic feeling. De Laurentiis brought in Italian production designer Danilo Donati, who had worked with Pasolini, Zeffirelli, and Fellini, to create highly stylized sets, from the blood-red palace on Planet Mongo to the Hawkmen’s city in the sky, with its ceremonial combat platform of retracting spikes wobbling above some kind of atmospheric vortex. Donati also designed the costumes, which are color-coded and often barely-there, exposing the hairy bodies of the virile Hawkmen and the sinuous limbs of moist-lipped Italian actress Ornella Muti, playing the nymphomaniac Princess Aura. Flash Gordon for much of the film just wears a tee-shirt that says “Flash,” which sums him up. He’s a quarterback for the Jets and he wants to stop the Earth from being destroyed; that’s about it. (Due to some behind-the-scenes drama with first-time actor Jones, in the end product he’s dubbed, though honestly it doesn’t make much difference.) Melody Anderson, primarily a TV actress, appealingly plays Dale Arden as an old-fashioned American girl who can deliver lines like (during a heated battle), “Flash, I love you, but we only have fourteen hours to save the Earth!”

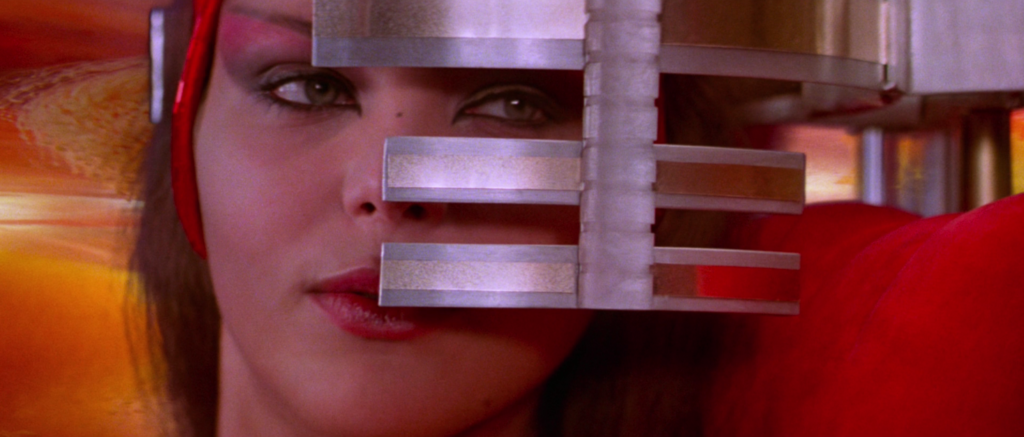

Ornella Muti as Princess Aura.

Topol of Fiddler on the Roof fame is wonderful as the benevolent mad scientist Dr. Hans Zarkov, and is granted the most dimension, unexpectedly, when his tragedy-laced past is tortured out of him in a frenetic montage. Brian Blessed receives the definitive role of his career as the boisterous, winged, mace-wielding Prince Vultan. British TV star Peter Wyngarde dons the Doctor Doom-like mask of Klytus. Timothy Dalton plays an intense, humorless Prince Barin with the same humorless intensity as his James Bond – and is made up to resemble Errol Flynn in The Adventures of Robin Hood. Deep Roy plays Aura’s “pet.” And then, of course, there’s Max von Sydow as an oversexed, incestuous, tyrannical Ming the Merciless with his trademark booming voice. The character’s “yellow peril” origins are somewhat defused by both the casting of the most famous Swedish actor in the world and a parodic Orientalist costume and makeup that suggests some extraterrestrial cultural appropriation, as if Ming only found about China while researching how best to upset it with earthquakes, volcanoes, and “hot hail.” There’s no racist potency here, not when everything points back to Alex Raymond’s original as though to say “this is what comics back then were like.” Which perhaps explains why so many genre fans took offense, misinterpreting the message as, “this is what all comics are like.” At the time, when there were so few comic book adaptations, fans were eager that comics be taken seriously.

Dale (Melody Anderson) and Dr. Zarkov (Topol) escape Ming’s clutches.

But in fact there was already a precedent for Flash Gordon, and it was the eerily similar parody Flesh Gordon (1974), which treated the material – not just the comics of course, but also the popular Buster Crabbe serial – with the same mix of nostalgia and loving send-up, albeit with a bit more sexual content. One of the many odd choices of Hodges’ Flash Gordon is that it’s almost as hot and bothered as that X-rated movie. Apart from the fixation on whips and chains, the story can’t quite pull free of the tractor beam gaze of Muti’s purring Aura, who invokes Prince Barin’s sexual jealousy by lusting after Flash. At one point she hops into Flash’s lap while he’s piloting her rocket (ahem), and is about to initiate him into Planet Mongo’s version of the Mile High Club before he reluctantly rebuffs her. (The fact that he’s also psychically linked to Dale when he complains that Aura’s turning him on adds just a touch of ménage à trois kink.) Further testing the film’s PG is a tongue-protruding, eye-popping death for Klytus; I didn’t notice all the sexual innuendo when I was a kid, but that left a mark. Gluing all these extremes together is Queen’s score (assisted by composer Howard Blake), in particular the two songs, “Flash’s Theme” and “The Hero,” both written by Brian May, and which nudge the movie in the direction of rock musical. Here, again, the Star Wars lead is ignored – nothing aping John Williams here, just a pulsing beat, squealing guitars, and Mercury’s operatic histrionics. Arrow’s new Blu-ray package has me appreciating that Flash Gordon is really a rock ‘n’ roll movie, a glam spectacle in which, hell yes, even some impromptu palace football is allowed.