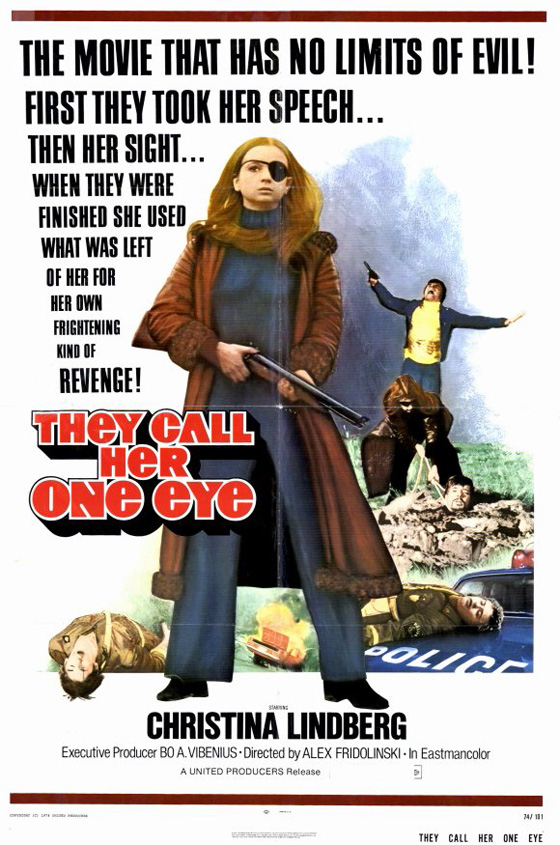

Now here’s a potent movie if ever there was one. The Swedish revenge film Thriller: A Cruel Picture (aka They Call Her One Eye, 1974) is, on the one hand, one of the most cynical productions ever made, for reasons which will soon become obvious. But it also demonstrates a willingness to hold nothing back; if there are moments in film which are called “pure cinema,” then perhaps Thriller is an extended and heavy dose of “pure exploitation cinema.” There’s something genuinely exhilarating about this particular kind of grindhouse picture: you don’t know what you’re going to see next. All standards of decency and good taste are out the window. The film was heavily cut in many versions, but in its original, unaltered form, it contains graphic shots of hardcore sex, scenes of shocking violence, and, hanging over it all, an overpowering sense of dread. The writer/director, Bo Arne Vibenius, worked on some of Ingmar Bergman’s films, including serving as assistant director of the seminal Persona (1966). Thriller carries that same overpowering, suffocating atmosphere. A famous scene in Persona literally melts the film. You get the sense that this could happen at any moment in Thriller, and you can’t take your eyes off it.

Frigga (Christina Lindberg) embarks on a date with the sinister Tony (Heinz Hopf) which will change her life.

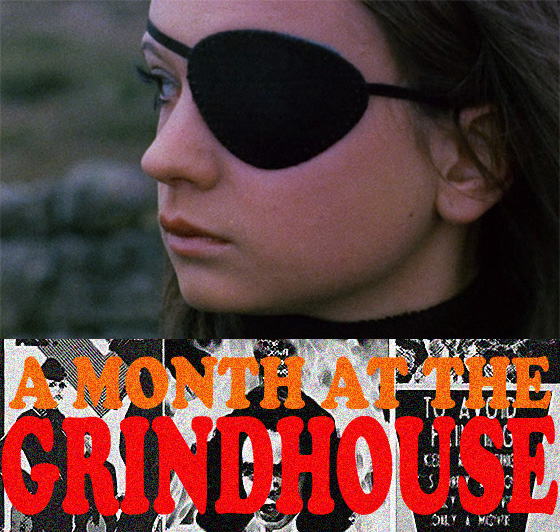

Mind you, it’s not a “Mondo” film overstuffed with sensationalistic taboo imagery. In many ways, it’s a spare and austere (and very autumnal) film, but the disturbing tone of its first, somber-paced half-hour leads the viewer to understand that some very, very bad things will soon unfold before our eyes – and indeed they do. Frigga (Christina Lindberg, Anita) – or Madeline, depending on the version you’re watching – is introduced as a porcelain-faced beauty in pigtails working on a farm with her parents. But this isn’t some Heidi fairy tale. Frigga is a mute, the result of a trauma depicted in a nightmarish flashback: an old man, spurting black bile from his lips, rapes her while she’s still a young child. (One gets the feeling this surrealistic vision is how she remembered it rather than how it actually happened.) Now her life is about to be derailed again. She makes the mistake of accepting a ride from Tony (Heinz Hopf, of the Lindberg film Exposed), a smooth-talking stud in a GTO. He takes her out to dinner, then brings her back to his house in the country and slips a mickey into her wine. We expect a rape scene, but he leaves her untouched: this is where the dread kicks in. He calls his friend, a doctor, who shoots up the unconscious Frigga with heroin. Then he calls up someone else, and says, ominously, that he’ll have another girl ready for him in a few days. It takes longer with the stubborn Frigga. When she comes to, she won’t be coerced into signing a letter that Tony’s prepared for her. But a signed letter gets to her parents anyway, explaining that she hates them, she’s met someone, and she’s leaving the farm behind for good. Tony explains ruthlessly: he’s been giving her doses of heroin, and her body has formed an addiction. He says she’ll die in 48 hours if she doesn’t get a regular fix. Holding up the bags of dope, he says, “You’ll get two of these a day if you do as I say.” Her first client arrives in her bedroom in a few hours. When asked to remove her clothes, she scratches off the john’s face. (“What will my wife say when she sees this?” he screams.) The wrathful Tony decides to punish her. He sticks a scalpel straight into her eye. From now on she wears a patch, and he describes her to clients as “the pirate.”

Frigga finds her only ally in the abused prostitute Sally (Solveig Andersson).

To get the heroin she needs, she succumbs to her visitors and bides her time. Her regulars include a man who aggressively snaps photos of her nude body, raping her with his lens; a thick-bodied thug; and a lesbian played by Despina Tomazani. (The scene in which Tomazani rapes Lindberg seems to indicate that director Vibenius wasn’t quite sure how lesbian sex works; she takes the missionary position and begins humping her like a man.) From a fellow prisoner, the sympathetic Sally (Solveig Andersson, Dagmar’s Hot Pants, Inc.), Frigga gets the idea to save money so she can successfully run away, and perhaps check into a rehab clinic. But two tragic incidents set Frigga on her own scheme. Her distraught parents drink poison with their milk (she sneaks away to visit the church after their funeral, wearing a red miniskirt and a matching red eyepatch). Then Sally is killed, a fact revealed in one of the film’s most effective scenes: Frigga discovers a bed covered in blood, sheets still dripping with it, the red pillow slashed down the center with the stuffing spilling out, and she presses her face straight into the bloody pillowcase and sobs. Frigga, who has been spending her spare time training in karate, marksmanship, and car racing, loads up a rifle and starts hunting down and blowing away her enemies one by one. Vibenius films each murder in extreme slow motion, Peckinpah-style: squibs exploding tee-shirts to pieces, blood arcing out of mouths in gracefully curved lines while heads recoil from Frigga’s brutal karate blows.

Frigga at target practice.

The film’s most extreme scenes carry a sense of recklessness, and that recklessness was apparently present on the set. Supposedly Vibenius took out a life insurance policy for Lindberg since live ammo was used in certain shots featuring the actress. The shooting also attracted the attention of the police, since (a) without the permission of the authorities, they dressed up a car to look like a police vehicle, and (b) without the proper permits to shoot in certain locations, they caused chaos while shooting their action scenes. In a 2009 interview with Film Bizarro, Lindberg notes that “I saw that people were running for their lives. Because what did they see? A crazy one-eyed girl with a rifle who started shooting at them… So I got reported to the police, and I got arrested. The director was never there when things like these happened.” Vibenius has his Un Chien Andalou moment in the film’s most gruesome and notorious image, as we see a scalpel going straight into Lindberg’s unblinking eye. As I watched this, I thought, That’s a very good makeup effect. It may not have been that at all. Some involved in the shooting of the film have claimed that Vibenius used his connection with a doctor to gain access to a cadaver, a female suicide victim, made up to look like Lindberg. If true (and Lindberg, who wasn’t present, says in the Film Bizarro interview that it’s very probable), it’s pretty sickening. The hardcore shots used in the uncensored version of the film are by comparison less bothersome, though, as with the X-rated cut of 99 Women (1969) and other “extended” versions of films from the era, they’re out of place, as clinical as birth footage, and artistically pointless except to cash in on porno chic.

Slow motion carnage dominates the film's last half-hour.

Obviously Lindberg was not involved in these genital close-ups, which were inserted at a later date using a sex act who called themselves “Romeo & Juliet.” But, being a model featured in various European magazines as well as Playboy and Penthouse, she had no issue with her frequent nude scenes, either. Thriller: A Cruel Picture would be one of her last major roles, after she’d made a minor splash with sex-infused dramas like Maid in Sweden (1971) and Exposed (1971). She’s a beautiful but curious screen presence, her childlike features – wide eyes and small lips – displaying a permanent innocence, but at direct odds with that giant eyepatch, the long black trenchcoat, and the bloody killing spree she embarks upon. (Quentin Tarantino, never one for subtle homages, used the Frigga eyepatch for Darryl Hannah’s character in the Kill Bill films.) Then there’s that ending. After showing us so much, the final killing is elaborately staged, with the operatic drama of a Leone Western – but spares us the money shot. The one killing that we really wouldn’t mind seeing is left to our imaginations. This is indeed a Cruel Picture.