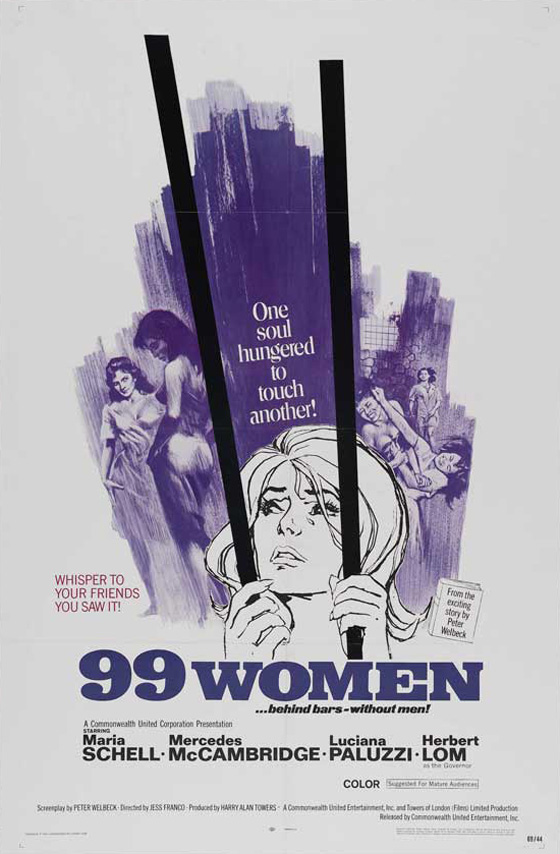

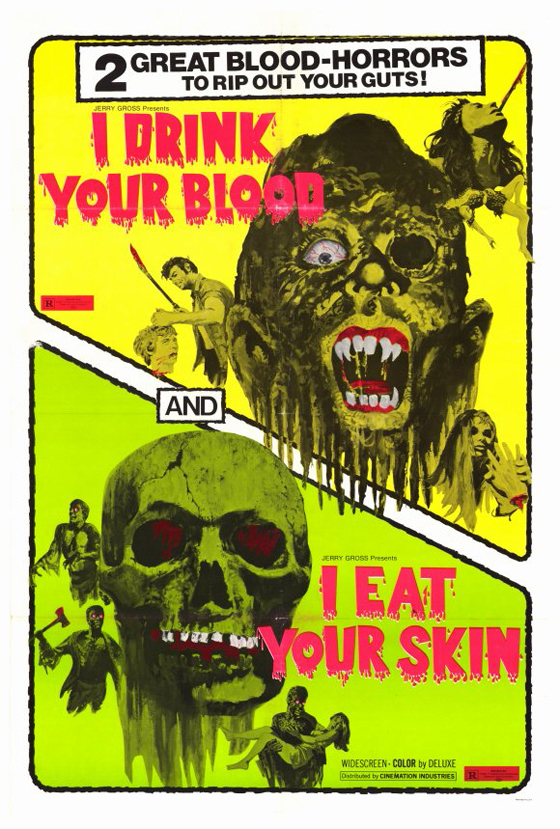

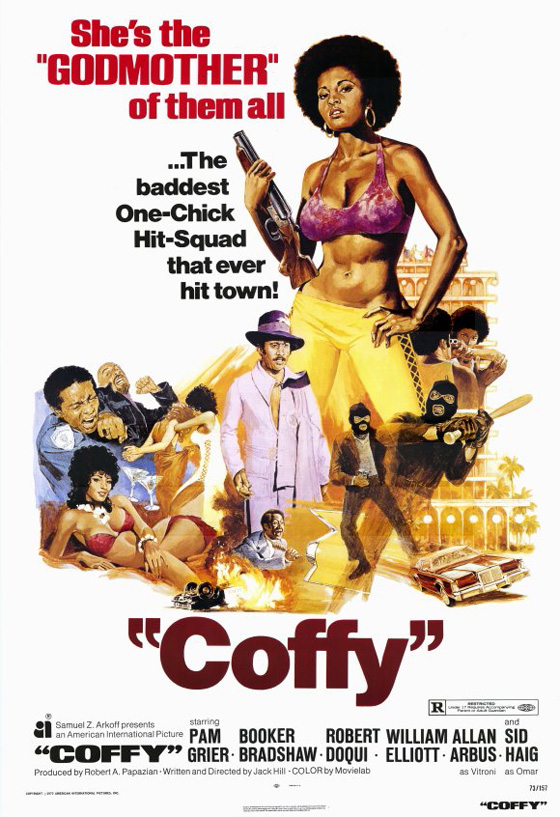

The IMDB attaches Jess Franco’s name to eight different films in 1969, including Venus in Furs with James Darren and Klaus Kinski, The Castle of Fu Manchu with Christopher Lee, and The Girl from Rio with Shirley Eaton and George Sanders. He was a busy guy. That year his film 99 Women also saw release, a grindhouse staple and a seminal film in the disreputable women-in-prison genre. The poster read, “Whisper to your friends you saw it!” This was really just another Franco exploitation quickie, applied with just enough spit-polish: he could still attract B-list celebrities to move tickets, and the built-in salaciousness of the subject matter did most of the advertising for him. Ninety-nine desperate women behind bars doing depraved acts! A sadistic female warden! The fat local governor who forces these women to submit to his lusts! A dangerous escape through an island jungle! 99 Women is like a sleazy pulp paperback come to life, delivering all the sadism and sex that the cover art advertised – and if that weren’t enough for you, it’s available in a hardcore version; just head around back.

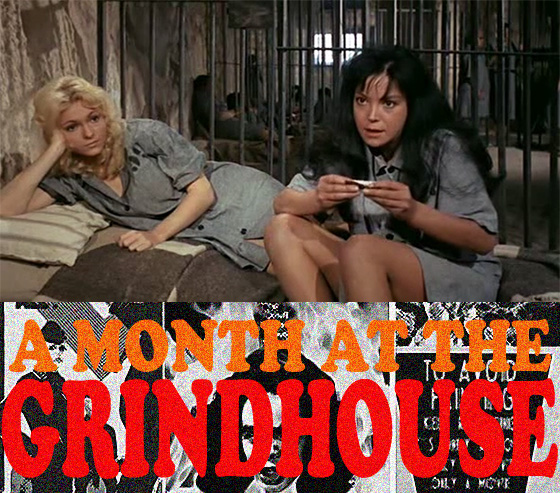

Prison director Diaz (Mercedes McCambridge) shows her potential replacement, Caroll (Maria Schell), "The Hole," where certain prisoners are held in isolation.

Here the marquee names include Mercedes McCambridge (of Giant and Johnny Guitar, and the future voice of Pazuzu), Maria Schell (White Nights), Herbert Lom (Mysterious Island, The Phantom of the Opera), and Luciana Paluzzi (Thunderball). I love all these actors, and have a particular obsession with Paluzzi, so this is a film I’ve always wanted to see. Imagine my disappointment to find out that she’s killed off in the first fifteen minutes; she lives just long enough to cash her paycheck. It’s just as well; I’d prefer to remember her as Fiona Volpe, and spare her the rest of Franco’s litany of indignities. But poor Herbert Lom – a man who once was in Spartacus – now reduced to playing serial rapist Governor Santos, and given an unconvincing double for ugly sex scenes in the X-rated version. McCambridge and Schell come off a bit better; McCambridge playing the sadistic Thelma Diaz, director of the women’s prison in a Spanish island castle called the Castillo de la Muerte, and Schell playing Leonie Caroll, sent on orders of the Justice Minister to inspect the prison – given the number of recent deaths – and potentially replace Diaz. Schell’s character appears to be the more compassionate, though Diaz and even the prisoners question her motives: maybe she just wants to sleep with the blonde girl in whom she’s shown so much interest. That girl is Marie (Austrian actress Maria Rohm, of Franco’s The Blood of Fu Manchu), whom Caroll rescues from a weeklong stay in “The Hole” when she first arrives on the island. The girls are usually just referenced by their number, and Marie is prisoner #99.

The beautiful Rosalba Neri as Zoe, Prisoner #76.

One of the prisoners, the redheaded Rosalie (Valentina Godoy, The Girl from Rio) hatches an escape plan with Juan, her lover from the male penitentiary, and joining her are Marie and a headstrong prostitute named Helga (Elisa Montés, Return of the Seven). When they arrive at the arranged place in the jungle, Rosalie learns from a different convict, Ricardo, that Juan has been killed in the escape. She sleeps with this stand-in anyway. As we more or less expect, the escape is doomed to failure: male prisoners being marched through the jungle catch a glimpse of the girls and riot, killing their guards and chasing the female prisoners through the trees. One girl is raped, and the other two make it to the boats, only to be met by a grinning Governor Santos. The old director, Diaz, is sent away, and Caroll replaces her – but learns that she can’t change the sadistic nature of the prison system when Diaz explains that the law requires the two escapees to be chained and whipped. Throughout 99 Women, there are brief glimpses of “good Franco.” The opening titles feature a rousing gospel-styled number called “The Day I Was Born” (sung by an anonymous vocalist), promising a film more swinging and lively than what we get. Franco stirs from his sleep in a flashback sequence illustrating the sordid history of one of the prisoners, Zoe (Rosalba Neri, Lady Frankenstein), a dream-like montage complete with candelabras, black lingerie, the staring faces of strangers at a nightclub while Zoe dances with her partner and indifferently smokes a cigarette, and the interruption of a gunshot, all to a lush and loungey score by Bruno Nicolai. (Sample dialogue: “One night I met a man. I was crazy for him. I didn’t know she was watching me.” Perfect.) The better Franco films can sustain this hypnotic mood and style for the entire running time. But 99 Women is really just one of those yellow paperbacks on the revolving rack; if you’re actually tempted to read it, you’ll get what you asked for.