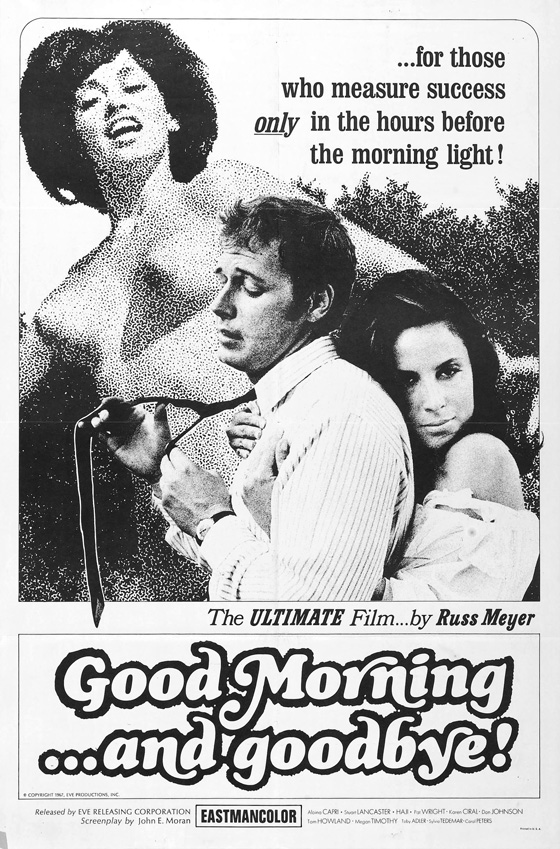

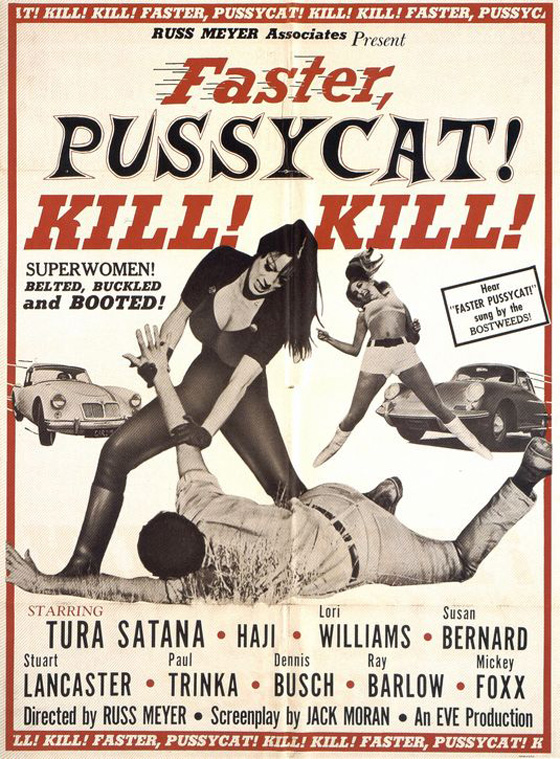

This is what a Russ Meyer fable looks like. Good Morning and Goodbye! (1967) makes its point clear with the subtlety of a jackhammer (you will note all the quarry imagery in the film). This is a film about being a man and pleasing your woman, ’cause if you don’t, she’s liable to cause trouble all over town. It’s a pre-Viagra tale of midlife impotence, and the only reason Meyer doesn’t use that word is because he’s too busy waxing poetic in his trademark long monologues, which read like parodies of TV commercials, but played over montages of skinny dipping and brassieres strained to bursting. “Burt, the Husband. He has everything. Bread, health, stability, and respect. Everything except manhood. Always staggering before the summit of sexual communion.” Burt Boland (Stuart Lancaster, the Old Man of Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!) is the insufficient patriarch of the troubled Boland clan. His unsatisfied spouse, played by Alaina Capri (Common Law Cabin), is “Angel, the Wife, a lush cushion of evil perched on the throne of immorality,” of course. “Let’s face, it Burt,” she says in her husky Mae West voice, “you’re the worst in town. Thank God I know someone in the country!” That would be the aptly-named Stone (Patrick Wright, who would go on to William Castle’s 1968 flop Project X and some notable exploitation films such as The Cheerleaders and Meyer’s Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens). Stone works at the quarry and services not just Angel but seemingly every bored housewife in the neighborhood – including the shrewish wife (Megan Timothy) of his best friend Herb (Tom Howland). The Bowlands’ hot-and-bothered daughter, Lana (Karen Ciral, The Undertaker and His Pals), spends her time dancing in the sun with her groovy boyfriend Ray, “a hip, long-haired, good-looking kid who can make out with most of the chicks the first time around.” (He’s played by one Don Johnson, who never worked long enough to make that other Don Johnson choose a different name.) Lana is desperate for Ray to deflower her, to which he can only respond, “Why can’t you just let things be? Let things happen. If it happens, fine, without all that jive dialogue.” This kind of talk threatens to drive Lana into the arms of the potent and always-available Stone.

Alaina Capri as Russ Meyer preferred to see her.

Luckily, help is on the way in the form of “The Sorceress,” played by the incomparable Haji, returning to Meyer’s filmography after a two-picture absence. Like a mute Greek chorus, she watches these players from a remove (or, to be more accurate, from the middle of a lake, before sprinting nude through the woods). She is “a woman who in the 17th century would have been burned at the stake, a child of gypsies…yet make no mistake, for she is a woman, this one. Blood runs fast and hot in her veins. Passion and sex exploding a scent of musk and earth that surrounds her body like a mist. She is a honeycomb with no takers, a witch that can fly only one night a year.” Haji alternately wears a cavegirl bikini and a more skimpy outfit assembled mainly of rose petals. After drawing Burt into the woods, she captures him in a snare that suspends him by his ankles, kissing him while he screams. Then she enacts a magical ritual, makes love to him, and sends him on his way. He’s no longer impotent. Like a superhero, he can now set right all that has gone wrong around him. As he strips before his wife, he declares, “All right, so you married me as an investment and didn’t draw the interest you deserved, so you’ve been moving your account all over the valley… There’s only one way to communicate with you, and it’s proving time right now!” Is this more inspiring than watching baby boomers play in a garage band over an announcer’s disclaimer about erections lasting longer than four hours? I don’t know, but I prefer it.

The Sorceress (Haji) restores manhood to the broken Burt (Stuart Lancaster).

Good Morning and Goodbye, whose opening credits are painted on the sides of colorful mailboxes while a red convertible zips by, is perhaps the purest (and crudest) depiction of the world as Russ Meyer saw it. The army vet, who liked to boast that he lost his virginity during WWII with the help of Ernest Hemingway, a Paris whorehouse, and a top-heavy woman named Babette, populated his pictures with three types: powerful women, tough guys who can please them, and measly wimps who can’t. His screenwriters helped him comically exaggerate his Popeye worldview (admitting that Olive Oyl would never pass the Meyer test). Here, he was aided by Faster Pussycat scribe Jack Moran, who also wrote this film’s equally ridiculous companion piece, Common Law Cabin (1967), originally titled How Much Loving Does a Normal Couple Need? Meyer might answer: “A lot!” To deliver his condemnation of men who aren’t manly enough, he applies his muse-of-the-moment, Alaina Capri, with her towering black hair, smug scowl, and overflowing cleavage. This would be his last film with Capri, who felt betrayed by just how much of her heaping flesh Meyer edited into the final product (after flirting with the mainstream, Meyer was drifting back toward skin flicks, finding his way toward the 1968 breakthrough hit Vixen!). Still, the nudity feels shoehorned in, largely confined to some naked sprinting through the countryside that bookends the film, and some disconnected shots in Meyer’s token opening montage (why there is a shot of playing cards scattering over a woman’s naked chest, I have no idea). As usual, it’s Meyer’s enthusiasm that wins you over. The message of this film is no deeper than those Charles Atlas ads found on the backs of comic books (“The Insult That Made a Man Out of Mac”), but while you’re locked in Meyer’s true believer stare, it’s easy to indulge in its self-described exploration of “the deep complexities of contemporary life as applied to love and marriage in these United States. All of the characters are identifiable, perhaps even familiar, and perchance you may view the mirror of your own soul!”