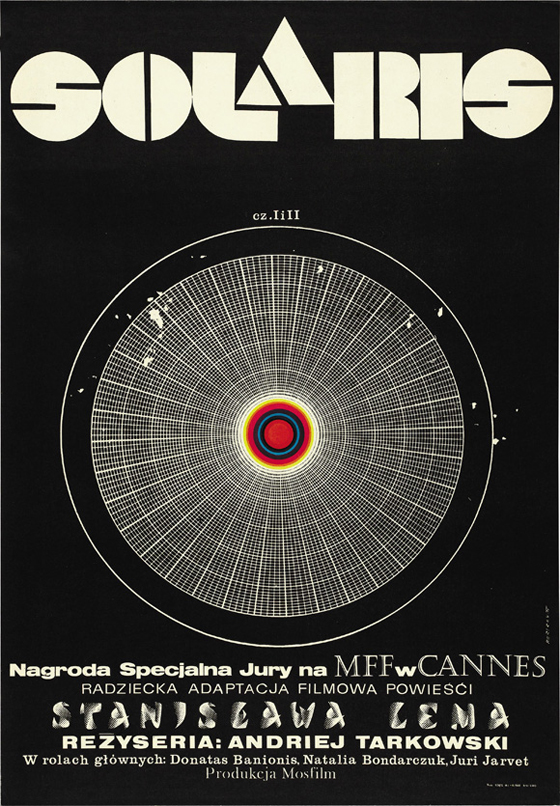

“I knew nothing, and I persisted in the faith that the time of cruel miracles was not past.” -Stanislaw Lem, Solaris (1961)

I don’t recall where it was, but when I first learned of the existence of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972), the film was referred to as the “Russian 2001.” I may have heard this more than once. Even on that first viewing – when I was in college, exploring a local video store – I knew that simplification was wrong, because I had seen 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and this was inexplicable in every way. At the time, I had not seen anything like Solaris, and fell under its spell. For me, it was a gateway film, part of an ongoing introduction to “art films” that had begun when I was in high school. But now, on the third or fourth viewing, the fallacy of comparing Tarkovsky’s film to Kubrick’s is even clearer, because Stanley Kubrick & Arthur C. Clarke were looking outward, and Tarkovsky & Stanislaw Lem were looking inward. Solaris is a film about exploring the cosmos and discovering not black monoliths that absorb all light, but a mirror that reflects with almost hateful clarity. Kubrick is often criticized for populating his films with characters that don’t seem human; Tarkovsky’s film is agonizingly human, and it is the tragic past of its central character, Kris Kelvin (Donatas Banionis), that becomes the alien world that traps him.

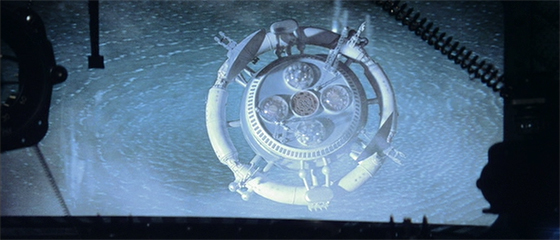

The Solaris research station, orbiting the oceanic planet of the same name.

Kelvin is introduced at his family home in the countryside, staring at submerged reeds wafting in the currents of a river. A former astronaut and scientist named Berton (Vladislav Dvorzhetsky) arrives and attempts to recruit him for a mission. The man formerly served aboard the Solaris space station, where he witnessed strange phenomena that seemed to be generated by the ocean planet the station orbited, also called Solaris. With research going moribund in the decades since Berton served at the base, and the scientists increasingly unstable, he asks Kelvin to travel there and determine whether the project should be aborted. The viewer might be forgiven for wrestling with the same decision regarding the film itself; the first forty-five minutes is mostly exposition followed by a long, wordless sequence in which Berton drives into the city. In what at first seems arbitrary, the film occasionally switches to black-and-white. As with all of Tarkovsky’s films, Solaris – which is just shy of three hours long – moves at a slow pace, more concerned with creating a hypnotic, meditative effect than accelerating the narrative. This, at least, he shares with Kubrick, though he makes it such a part of his style that his films are an acquired taste, and not for everyone. But stick with him, and he rewards.

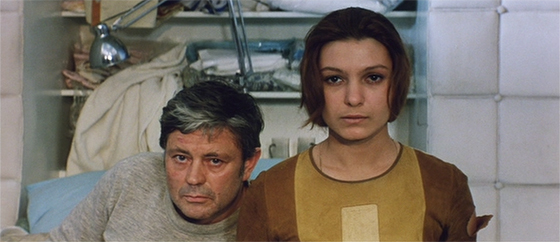

Kris Kelvin (Donatas Banionis) encounters the manifestation of his dead wife (Natalya Bondarchuk).

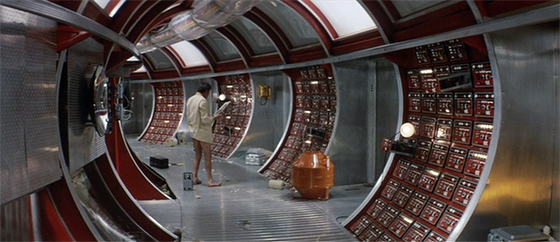

Once you get past the slow preamble, the plot quickly becomes intriguing. Kelvin arrives at a very lived-in space station that’s succumbing to disarray, if not decay; junk is scattered everywhere, and the snaking corridors are vacant and quiet. He only finds two inhabitants remaining, and they keep secretively to their quarters: Dr. Snaut (Jüri Järvet) and Dr. Sartorius (Anatoliy Solonitsyn) warn him that that their experiments with blasting the waters of Solaris with radiation have produced alarming results; a third scientist, Gibarian, is dead, and the planet is creating physical manifestations within the research base. Kelvin catches brief glimpses of them within the doctors’ cabins: a sleeping child and a fleeing dwarf. It isn’t long before Kelvin gains an unwanted companion of his own. A beautiful woman named Hari (Natalya Bondarchuk) joins him in bed, spooning, and he breaks into a nervous sweat. This is his wife, who died years ago. The details of her death will emerge slowly over the course of the film, and explain the increasingly obsessive behavior of both of them. Still, his immediate reaction is to shuffle her into an escape rocket and fire it out of the ship. Dr. Snaut’s promise that she’ll return quickly comes true. When Kelvin tries to lock her inside his quarters, she breaks through the door, tearing her flesh to shreds in the process. He gives up; they can’t be separated, and so they won’t be. But Hari soon begins questioning her fragmented memories, and who and what she truly is. Helpless, Kelvin watches as their past is reenacted, repeatedly, tormentingly.

Hari refuses to let Kelvin go, and nearly tears herself to pieces to prove it.

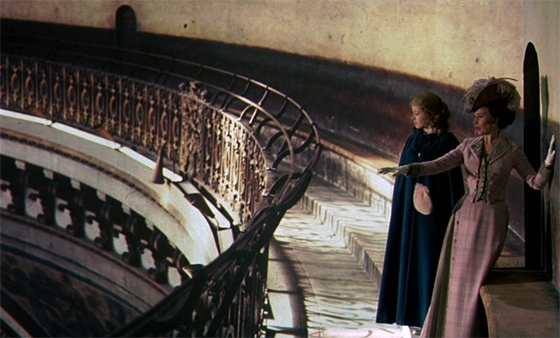

Tarkovsky’s decelerated pace is not leisurely but intense, nightmarish. As Solaris progresses, the discomfort rises, like a slowburning horror film, all of it leading to a final scene that’s delirious, unnerving, haunting, and extraordinary. Prior to this denouement, Tarkovsky serves up numerous tour de force sequences, many involving his trademark long takes and extended tracking shots. In one, we see a dream (?) of Kelvin’s, in which the camera pans back and forth through his cabin and its circular window – blinding-bright with sunlight – as we see ghosts walking back and forth: his young mother, his family dog, and one Hari after another, endless clones of her, backs turned, until finally the camera settles upon her staring, accusatory face. In a quietly beautiful scene, Tarkovsky closes in on a painting of a wintry village in the country, evocative of either Kelvin’s past or just an idealized one, before the director suddenly cuts to Hari and Kelvin drifting off the floor, clutching one another, the Solaris‘s artificial gravity giving way to weightlessness. They have literally become suspended in their past.

Kelvin explores claustrophobic corridors of Solaris.

A frequent theme in the director’s work is painful nostalgia; his film The Mirror (1975) is so abstractly nostalgic, and so personal, that it almost becomes impossible to decode. Solaris is not so impenetrable, and the disconnected images from Kelvin’s past can easily be accepted by the viewer for what they are; what makes them especially fascinating is how Tarkovsky visually links them to the influence of the ocean planet. We first see Kelvin as he’s contemplating a river, and in at least one shot Hari is accompanied by a sparkling waterfall at the corner of the frame, a visual clue that will connect to a critical moment at the film’s conclusion. Kelvin’s past is Solaris, he is in its tides and in the vaporous clouds hanging above them. (When Berton explains to a committee that he saw a four-meter-tall child standing upon the planet’s surface, his evidence, the camera footage, plays back only the clouds.) Kelvin’s journey to this alien world is undermined by his realization that he may have always been there.

Solaris is available on Blu-Ray from the Criterion Collection. The 2002 remake, by Steven Soderbergh, fails to capture the mystery and devastation of Tarkovsky’s film, and doesn’t move any closer to Lem’s original novel to make it an interesting alternative.