Female Vampire (1973) is a love story, but not between the sexy vampiress Irina Karlstein and the mustachioed author who falls under her spell. It’s the love story of Lina Romay and Jess Franco. Franco had first met Romay, the girlfriend of a photographer in his crew, while shooting The Rites of Frankenstein (1972). As the late director explains on an extra on the new Blu-Ray of Female Vampire, he met her in an elevator and knew, instantly, that they would be together. Only a few years prior he had lost his dark-haired Spanish muse, Soledad Miranda, the strikingly beautiful star of his films Vampyros Lesbos (1971) and She Killed in Ecstasy (1971) – tragically killed in a car accident in Portugal. Romay could have been Soledad’s sister: the Spanish amateur actress had the same cat-like eyes, flowing black hair, sensuous body. Immediately they joined forces, sexually and creatively, for films like The Sinister Eyes of Dr. Orloff (1973), Female Vampire, The Perverse Countess (1974), Exorcism (1974), and many others. For his camera, she followed him merrily into increasingly explicit material, and eventually began shooting her own films; they were libertines, uncompromising explorers, and were together through their late marriage in 2008 and until her death from cancer in 2012. Franco did not last much longer without her, and passed away this last April at the age of 82.

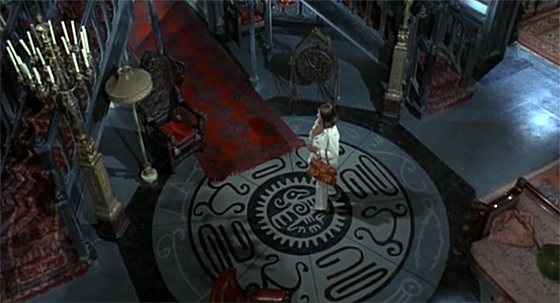

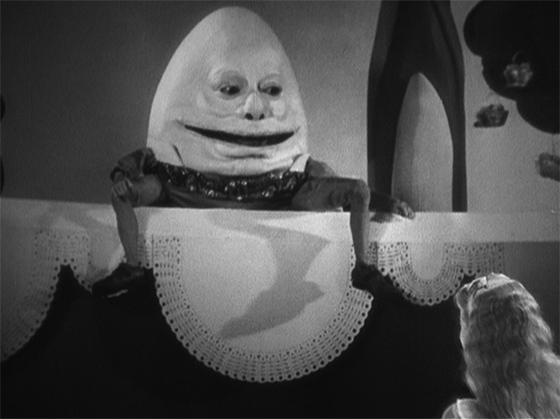

Lina Romay as Countess Irina Karlstein

Romay – real name Rosa María Almirall Martínez, her pseudonym taken from a Mexican-American performer who had some popularity in the 1940’s – was just nineteen when she became Franco’s Irina Karlstein; the director was forty-three. It is evident from the very first frames that she has become his obsession. On what seems to be a very chilly morning, she struts out through a misty countryside wearing only a black cape and a leather belt that supports nothing. Franco’s camera, zooming as always, scans her body up and down, drifting in and out of focus. This will be the main subject of the narrative, such as it is. She encounters a handsome young farmer, seduces him wordlessly, and finishes him, so to speak, during the act of oral sex, while he’s pinned against a chicken-wire fence. The mute countess travels with her hulking, grunting assistant to the Portuguese island of Madeira, where she stays in a hotel room overlooking the pool – inspiring another Franco zoom, this into the sparkling blue waters. A blonde female reporter in a bikini asks for an interview, leading to some awkward dialogue about Irina’s ancestors and rumors of their vampirism. She has a young man brought to her room, and again kills him with her head between his legs; once he’s dead, she finally straddles him to achieve her own orgasm. But she’s indiscriminate, and seduces and kills the female reporter in a similar fashion, all to the lush, lounge-y soundtrack by frequent Franco collaborator Daniel White. An author pursues her, professing his love for her; she is moved, but tries to resist, for his sake. Meanwhile, Dr. Roberts (Franco) and blind Dr. Orloff (Jean-Pierre Bouyxou) investigate the killings, leading to a theory – supported by a fang-punctured clitoris – that the killer is a vampire who feeds off more than just blood.

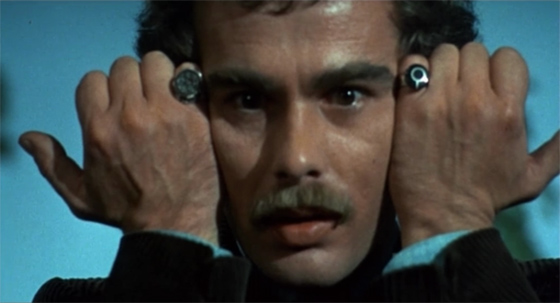

Jess Franco as Dr. Roberts, no relation to the Beatles.

A more typical horror effort would end with a lynching and a staking, preferably at a Gothic castle, but the two would-be Van Helsings instead become fascinated by the beautiful Irina. Orloff – who may or may not be the same character as in Franco’s notorious Dr. Orloff series – puts it this way: “How are we to know that the pleasure felt by the victims isn’t worth their life?” The key scene comes in Female Vampire‘s ambiguous ending, as Dr. Roberts breaks into Irina’s home and spies upon her while she writhes naked in a bathtub filled with blood. For a long while we are alone with Irina before the intrusion. Franco’s camera simply studies her voluptuous body, turning over and over in the red water; and then we see the man who is gazing, Franco himself, as he stands at the door and watches. At last Lina Romay’s face sinks down below the surface, completely submerged, in an eerie image of death, while her director continues to watch, in love. Unlike some of Franco’s other films, Female Vampire is not sleazy. It’s an erotic poem, repeating the same images – the flapping wings of an avian hood ornament, the flapping arms and fluttering, diaphanous cape of Romay as she prepares to turn into a bat (never seen), the image of Romay walking through the fog in her Vampirella garb, Romay’s breasts, Romay’s hips, Romay’s black pubic hair, Romay’s lips, and Romay, Romay, Romay. Franco was under a spell he’d never shake himself from, and Female Vampire simply captures it in 35mm. In this way, his film about a “nice vampire” is human and touching.