During WWII, Spanish born model Maria Montez enjoyed a brief burst of stardom, under contract with Universal and appearing in a string of pulp adventures and thrillers that were sold on her exoticism and sensuality. Following bit parts in films like The Invisible Woman (1940) and That Night in Rio (1941), Montez began to make a name for herself as a pin-up ready beauty in the likes of South of Tahiti (1941) and Mystery of Marie Roget (1942), striking it big with Arabian Nights (1942), a costumed, Technicolor semi-spectacle that spawned a follow-up (1944’s Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves) and many imitations. Her chiseled, charming co-stars in that film were Jon Hall and Sabu, the often-shirtless young Indian actor who had become an unlikely matinee star thanks to roles in the Alexander Korda productions The Thief of Bagdad (1940) and Jungle Book (1942). Together, the three were reunited for the island adventure film White Savage (1943), and then the very similar Cobra Woman (1943). Kino has just released Arabian Nights and Cobra Woman on Blu-ray, which would make a wonderful, colorful double feature, but today we are here for the latter film. Cobra Woman bears the reputation of a camp classic, but it’s an utter delight even if enjoyed solely for its derivative thrills.

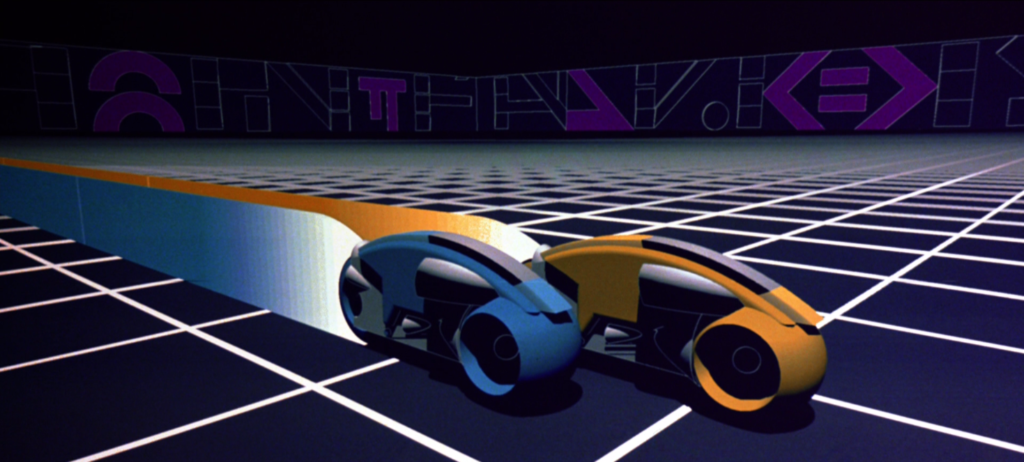

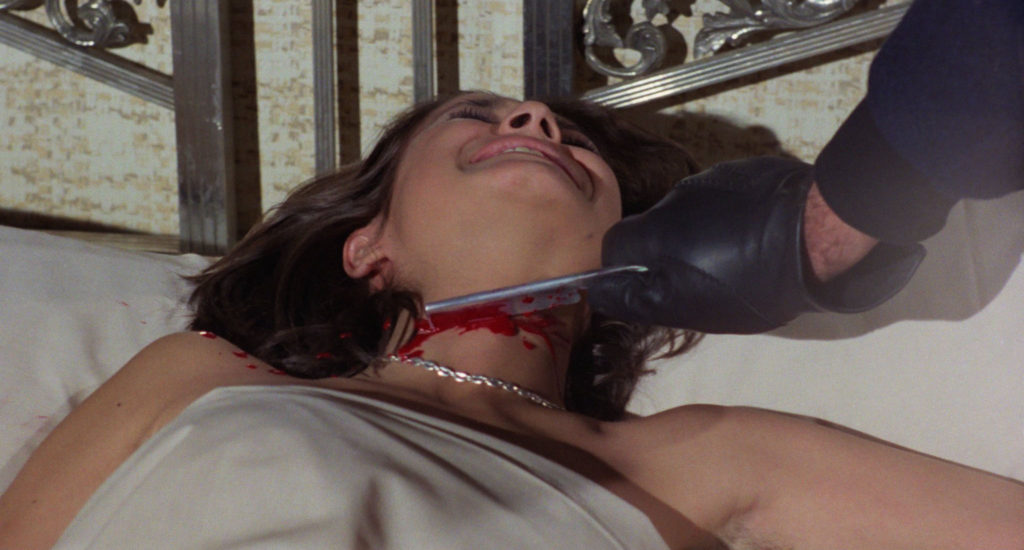

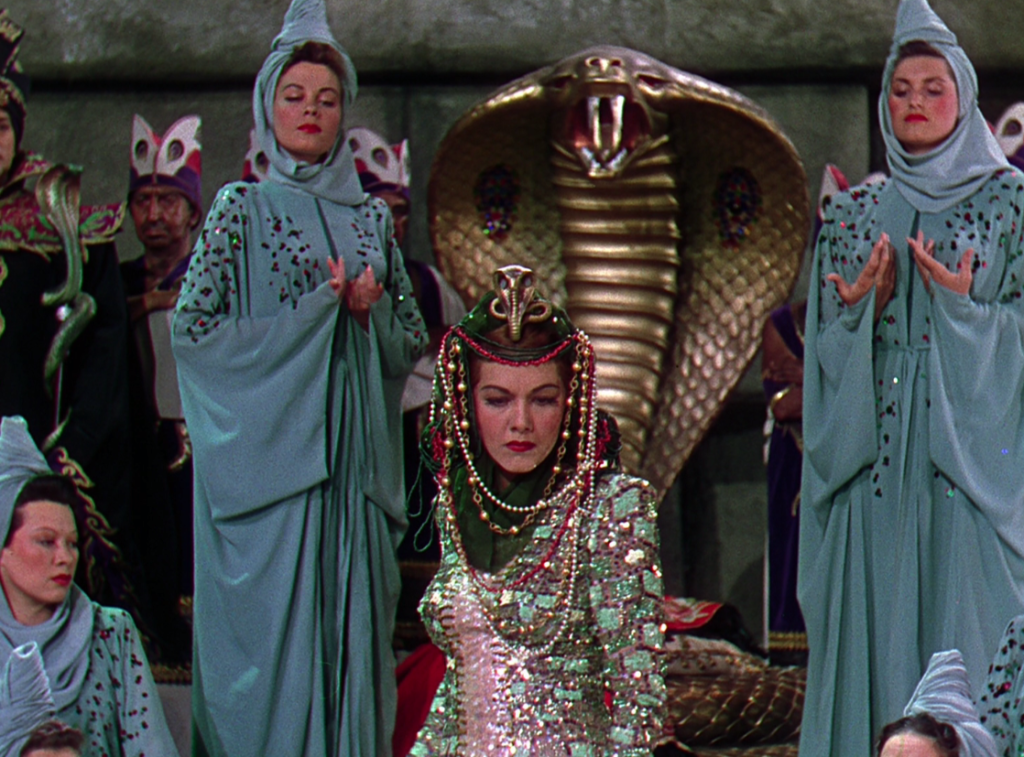

The evil high priestess Naja (Maria Montez) prepares to dance with a giant king cobra.

Montez is ambitiously cast as twin sisters, good and evil, who were separated following a cobra bite ritual to determine who should be the high priestess of Cobra Island, which lies somewhere unspecified in the South Seas. The sinister, power-hungry Naja endured the bite with no protest and was chosen, but Tollea, suffering from the poison, was sentenced to death. An outsider who found his way to the island, the Scotsman MacDonald (Moroni Olsen, Notorious), is given Tollea so she can be smuggled away on his boat. But our story begins on a nearby island, as the grown Tollea prepares to wed Ramu (Hall) with MacDonald’s blessing. Sabu plays Ramu’s (shirtless) companion Kado, and keeps a pet chimpanzee named Coco. One day this group meets a mysterious stranger, Hava (Lon Chaney, The Wolf Man), pretending to be a blind and mute beggar, who abducts Tollea after killing one of her servants with a musical pipe outfitted with two prongs dipped in cobra poison. MacDonald confesses Tollea’s backstory to Ramu, and surmises that she’s been taken back to Cobra Island to be killed. Ramu, Kado, and the chimp set off to rescue her, but their plans go awry when Naja falls for Ramu (who at first mistakes the woman for her sister, and embraces her while she’s taking a swim). We also learn that the high priestess, with the menacing Martok (Edgar Barrier, Phantom of the Opera), has been using the swelling ranks of the local cobra cult to steal influence away from the island’s proper queen (Mary Nash, The Philadelphia Story), who sent for Tollea so she can usurp her sister’s place.

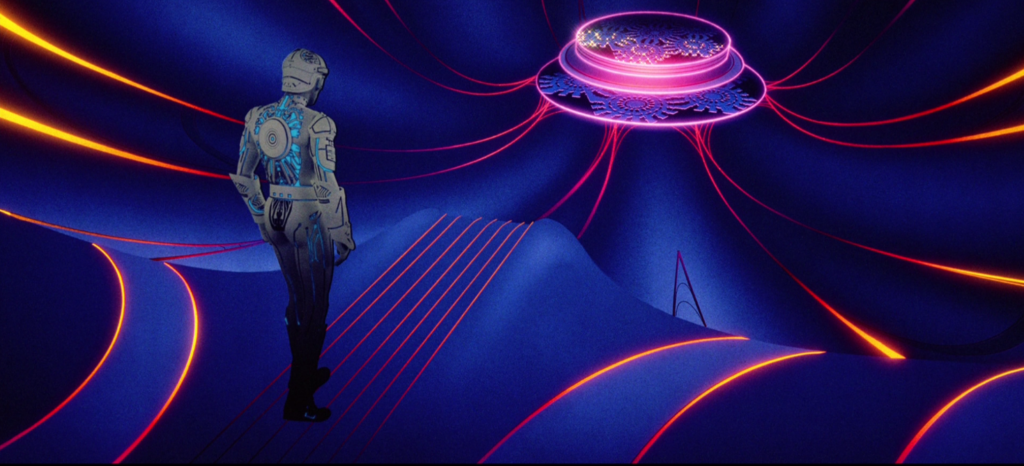

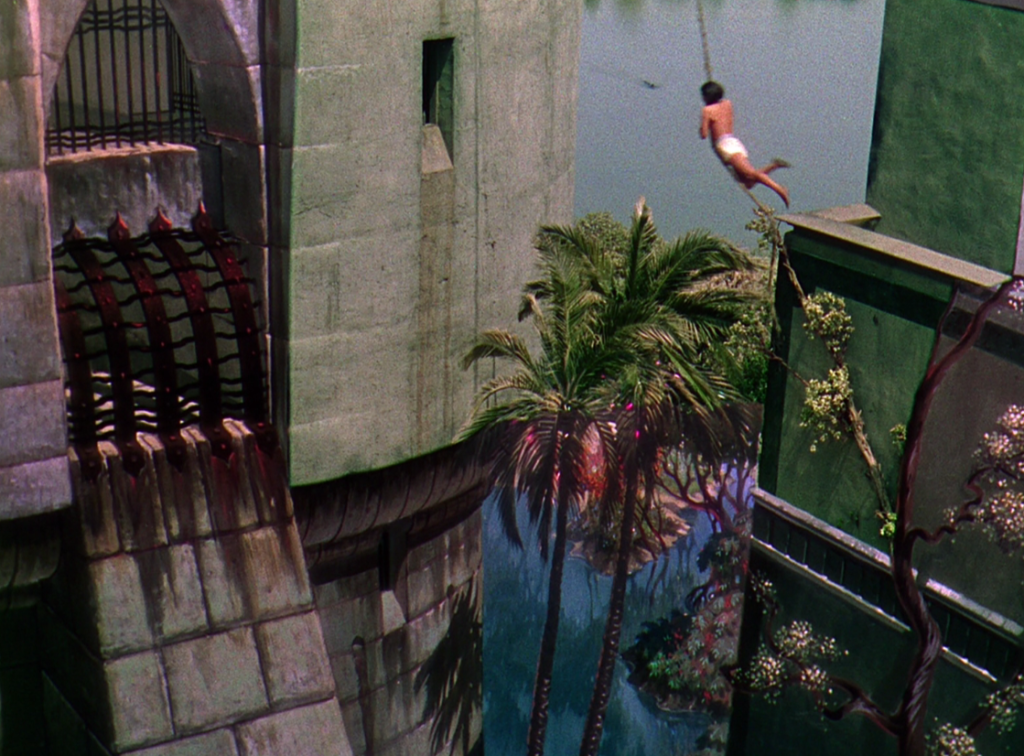

Sabu and Jon Hall explore Cobra Island.

The expected problematic colonialist-pulp elements don’t cause too much offense since it’s not really possible to discern just what’s being stereotyped or exoticized. True, Sabu’s character is unsurprisingly servile, and most of the island inhabitants – those who are the extras – are brown (or skin-darkened thus) and easily dominated by their white priestess, but the film’s peculiar, random constellation of influences and designs places this in the realm of pure fantasy; we might as well be in Oz rather than some quasi-Tahiti. It’s all too generic and silly, as one can tell just from the character names, which all sound like villains from 60’s Stan Lee/Jack Kirby comics. Naja ends her pronouncements with: “I have spoken.” When she’s not standing in her cobra temple, she’s lounging in an Arabian Nights-styled harem, glowing amongst her white serving girls as if to suggest they glorify her with a bit more than just food and drink. She bathes in a one-piece silver swimsuit that looks more like a form-fitting dress, and later – in the film’s kitsch showstopper – opens a ceremonial robe to reveal a sequined gown and performs an erotic dance before a giant snake puppet, which lunges toward her with its phallic head. This suddenly works her into a psychopathic sexual frenzy, and from the crowd she picks out human sacrifices for the volcano, who are immediately seized and carried away. Meanwhile, Jon Hall just walks in and out of the palace as he pleases, apparently; even after he’s captured by Martok and thrown in a dungeon, he turns the tables, steals Martok’s “cobra sword” and robe, and struts around as though no one could possibly recognize him now. Naja is only excited by his antics, wishing to marry him so they can rule the island together, but he rebuffs her, and she has the island searched for Tollea. One hopes that the final sisterly reunion will be accompanied by some Parent Trap-style split-screen, but alas, this is not the case.

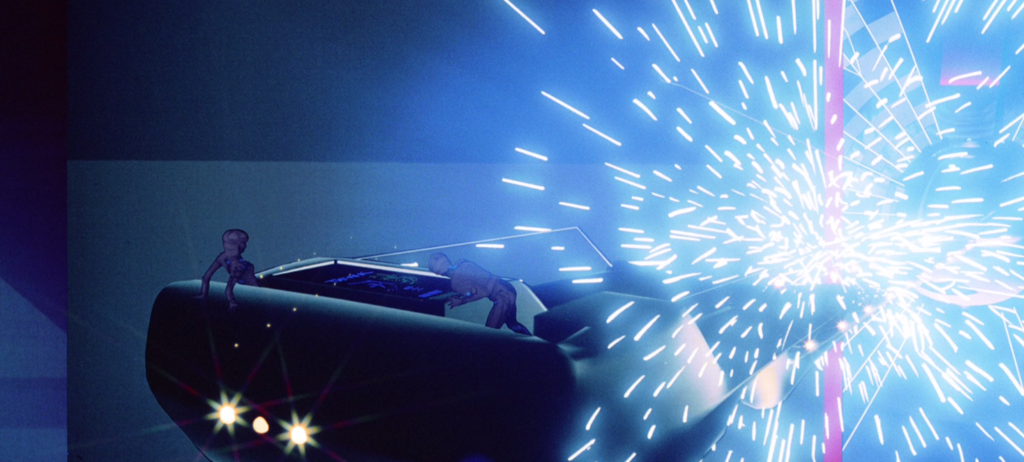

Sabu swings into action.

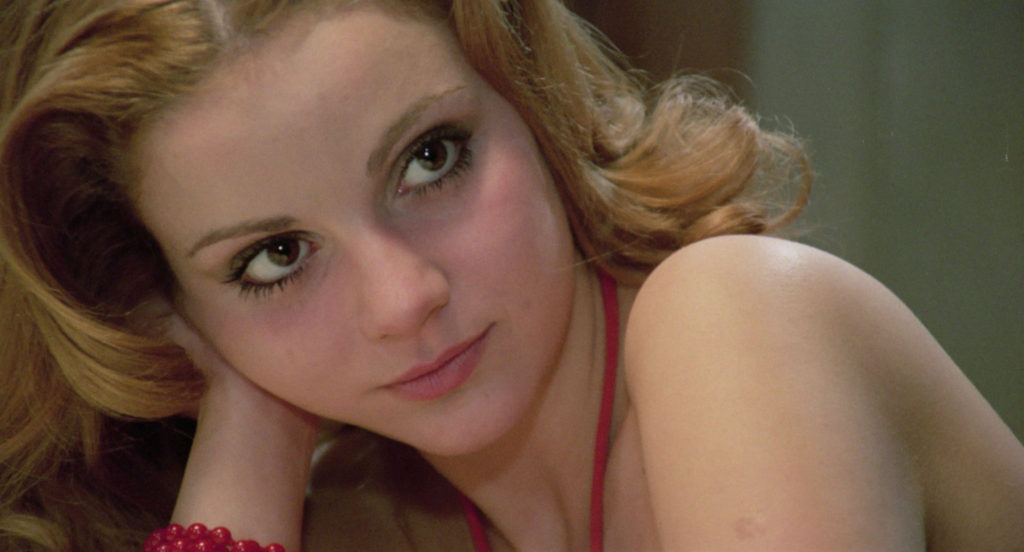

For all the criticisms Montez receives as an actress, she deserves a bit more credit: despite the incongruity of her Spanish accent – and everything is incongruous here – she performs as well as one can reasonably expect with this material. Once her two characters meet, it is obvious to the viewer which sister is which, as she plays Tollea with the right amount of uncertainty and softness. (It makes sense that, at this stage, both Hall and Sabu can recognize the real Tollea straight away.) And as viewing for a lazy afternoon, the film has much to recommend it: Technicolor that pops, fun matte paintings and set designs, and sequences that seem to have influenced the likes of Conan the Barbarian (the giant snake ritual) and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom – witness the rope-swinging to and from the temple platform in the climax and try not to think of Indy in the temple of Kali. Director Robert Siodmak, now well-regarded for thrillers like Phantom Lady (1944), The Spiral Staircase (1946), and Criss Cross (1949), squeezes every ounce of entertainment that he can out of some pretty thin ingredients, and does so in a tight 71 minutes. Never mind that the climax is abrupt and fails to disguise its brazen illogic. It’s the sort of movie that, a decade later, would have been made in 3-D with spears flung at the audience. Plus, the dialogue: the cultists chanting “King cobra! King cobra!” and Montez declaring, “It is the cobra law!”…you could enjoy a productive drinking game around the word “cobra” alone.