John Harrington (Stephen Forsyth) is handsome, seductive, and constantly surrounded by beautiful women – in bridal gowns. His Paris-based studio designs wedding dresses, and he lords over his models like a sheik in his harem. His wife Mildred (Laura Betti, Teorema) has become shrewish in her intense jealousy and resentment, and to John she’s just as heavy a burden as that detective, Inspector Russell (Jesús Puente), who keeps dropping by unannounced, asking probing questions about the women in Harrington’s circle who’ve gone missing. Meanwhile, Harrington, who narrates Hatchet for the Honeymoon (1970), calmly informs us that he’s a madman. He’s been murdering women before their wedding day, then feeding their bodies to an incinerator, which issues black smoke through a tall chimney. With each murder, Harrington – who frequently retreats to his childhood room, kept intact like a museum piece, replete with wind-up toys and a model railroad – begins to unlock repressed memories from his youth. He actually sees his younger self standing nearby and watching while he attacks with his shining meat cleaver. And images return to him from the past – the sight of his mother being murdered, something he witnessed, something he wishes to solve no matter how many women he has to kill to reveal the clues hidden in his unconscious mind.

John Harrington poses one of his potential victims in his private, mannequin-filled studio.

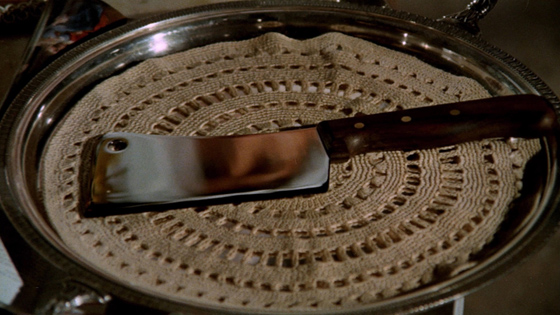

Story originality isn’t a major strength of Mario Bava’s Hatchet for the Honeymoon, an Italian/Spanish co-production which obviously builds upon Psycho and Peeping Tom (1960) – Harrington even commits one murder while wearing a dress and lipstick, Norman Bates-style – but also recalls Buñuel’s The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz (1955), René Clément’s Purple Noon (1960), Truffaut’s The Bride Wore Black (1968), Poe’s “The Black Cat” and “The Tell-Tale Heart,” and any number of gialli that preceded it: it comfortably fits into a long and rich tradition of stories told by murderers attempting to cover up their increasingly sloppy crimes. The “twist” ending – when Harrington finally unlocks the full memory of his mother’s murder – is really not a twist at all, since we can see it coming almost as soon as that narrative element is introduced. But Bava is using this most basic template to play with all his cinematic toys, like Harrington in his childhood playroom. Hatchet for the Honeymoon is a sensory experience, almost completely subjective, wedding itself with real commitment to its mad narrator’s point-of-view. When he prepares to commit murder, Bava cuts quickly between the present and the past, with disorienting shots of the meat cleaver being lifted, in an appropriate cinematic representation of psychotic delirium.

Harrington (Stephen Forsyth) at the incinerator.

Bava not only directs, he takes the title of director of photography, which allows for some interesting experimentation, such as one squirm-inducing shot in which we see a shaft of light upon Harrington’s eye, his face in darkness, then disappearing entirely – until it suddenly leans out of the dark and toward the camera in extreme close-up, as though he’s crawled out of the screen and is now right up against us. The blood-red glow of the incinerator is appropriately hellish, to contrast with the lush, Eden-like gardens of Harrington’s estate. Midway through the film, Harrington finally turns his weapon against his wife Mildred – he serves it up on a silver platter. Her body is one that won’t easily disappear, a point Bava delivers with evident pleasure. While her corpse is sprawled upon the stairs, below Harrington greets Inspector Russell and the angry groom trying to locate his missing bride. Bava films Mildred’s dangling, bloody hand from every angle, all to frame the moment the audience is anticipating: droplets of blood falling from her fingers, down toward the unwelcome visitors and smacking against the carpet. It’s truly worthy of Hitchcock.

The maid pours a drink for the ghost of Harrington's wife.

Even when she’s been fed to the furnace, the ashes poured into a leather carrying-case, Mildred will not go away. She begins to haunt her husband, but – in a reversal of the usual cliché – she can be seen more often by others than by Harrington. Unlike his other victims, she refuses to go missing: everyone can see her at his side, even when he cannot. Defiant, he carries the bag with her ashes to a dance-club. When he tries to pick up a go-go dancer, she objects that he already has a woman at his table, though he sees only the pouch; undisturbed, he suggests a three-way (and is slapped). When we do see the ghost, actress Laura Betti is given grayish make-up and lit in such a way as to resemble the specter in Bava’s Kill, Baby…Kill! (1966) – though nothing is as disturbing as Betti’s smug and satisfied expression. Bava visually makes clear the film’s ultimate message: that Harrington can murder as many brides as he likes, but his own wife will never leave him – adding an element of black humor to the film’s final scene. The score, by Sante Maria Romitelli, may sound dated, but provides a nice counterbalance with its overtly romantic theme, and the opening credits, impressionistic images of Forsyth’s face beneath blood-red paint-strokes, sets the mood for vintage Bava. Available in an attractive Blu-Ray from Redemption/Kino, with an audio commentary by Bava scholar Tim Lucas.