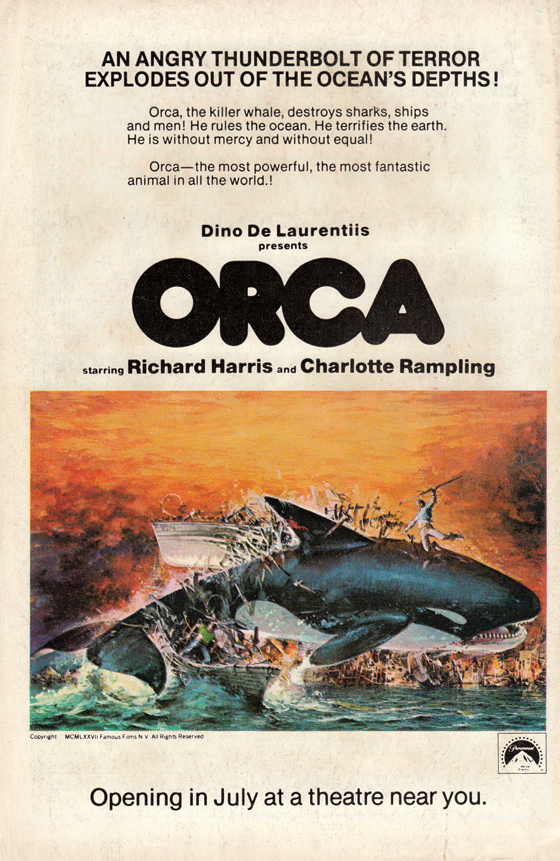

The message of Orca (1977) is clear: killer whales are beautiful, intelligent creatures who should be appreciated as thus, for if you cross them, they will ram you hard with their noses and chew you into bloody bits. “The ancient Romans called him Orca Orcinus, Latin for ‘The Bringer of Death,'” intones professor Charlotte Rampling to her class near the beginning of the film. “As parents, killer whales are exemplary, better than most human beings. And like human beings, they have a profound instinct for vengeance.” After explaining the depth of the killer whale’s communication by playing some whalesong (“[this] was found to contain over fifteen million pieces of information; the Bible contains only four million”), she concludes: “What we call language, they might call unnecessary, or redundant, or – retarded.” Here the scene ends, for is there anything more to say? Those whales at Sea World think you’re retarded. We witness a shark stalking a diver, and just as the shark is about to strike, it’s suddenly rammed by a charging orca so hard that it catapults out of the sea, covered in its own blood. The film has announced its intentions. It’s seen Jaws, and it has a lunatic inferiority complex.

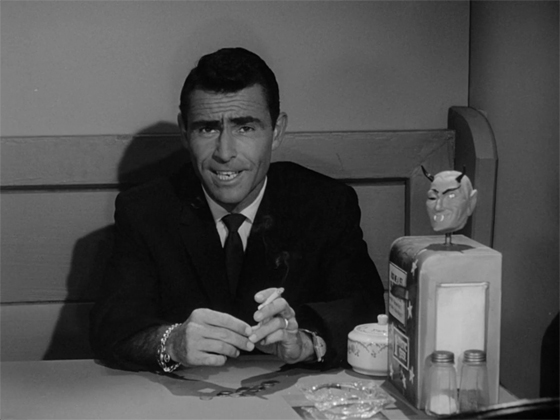

Captain Nolan (Richard Harris) and his crew capture a female killer whale, while her vengeful mate watches from below the surface.

Such subtlety never lets up for the film’s ninety minutes. The opening shot of the film, eager to emphasize the awe and magic of killer whales, shows two of the beasts doing parallel flips out of the sea, against a setting sun and while mournful Ennio Morricone music plays; like much of the whale footage in the film, this is taken from Marine World/Africa USA in San Francisco, here overlaid into the ocean so poorly that the whales are semi-transparent. Even if the effect did work, it would be to support a mise-en-scène better suited to a black velvet painting at a sidewalk sale. But the collaborators – including director Michael Anderson (Around the World in 80 Days, Logan’s Run), screenwriters (and former Sergio Leone collaborators) Luciano Vincenzoni and Sergio Donati, and executive producer Dino de Laurentiis (fresh off his remake of King Kong), are aiming for an emotional effect more potent than Jaws. Theirs is a tale of existential guilt, to be embodied in the raw performance of Richard Harris as Captain Nolan, a man whose troubled relationship with a killer whale brings back traumatic, unresolved conflicts from his past. Also, the orca bites Bo Derek’s leg off.

Orca wreaks his vengeance against the Newfoundland fishing village.

Anxious to test his shark-wrangling mettle against a killer whale, Newfoundland fisherman Captain Nolan steers his vessel Bumpo into a shoal and snags a female. The whale would rather commit suicide than be captured by a mentally-insufficient human, so she flings herself against the boat’s propeller, leaving Nolan to drag out of the sea a hemorrhaging orca chained at the tail. While her husband watches from the sea (close-ups of a whale’s crying eye), she spontaneously gives birth, dropping a large, pink orca fetus onto the deck of Nolan’s ship. (The film is rated PG.) Horrified, he hoses the stillborn thing back into the ocean. We see the male orca scream in rage at the sky, then proceed to attack the boat and swallow Keenan Wynn. What follows is a killer whale funeral procession, as the mourning husband, joined by his whale companions, pushes his dead wife with his nose for miles and miles against the current, until he deposits her carcass upon a beach. Morricone’s score tries its damnedest to sell this. Harris’s Captain Nolan, meanwhile, is in despair. We’re soon to learn that he lost his pregnant wife in a car accident with a drunk driver, so, as he puts it, “I understand what that whale is feelin’, for the same thing happened to me.”

Harris and Rampling confront the killer whale inside the Arctic Circle.

It might be best to interpret what follows as a fairy tale, for it sure as hell isn’t connected with reality. The enraged killer whale terrorizes the Canadian fishing village, demanding that Nolan come out and face him mano-a-orca in the open waters, which the local fishermen understand because the whale has eaten all their fish and sunk several of their boats. The angst-ridden Nolan only gets conflicting advice from Rampling’s Dr. Bedford, who one moment tells him that the whale is seeking “vengeance,” and another moment tells him he’s crazy for trying to read into the whale’s actions. (“Nolan, I think I ought to explain something to you. I don’t know what this creature wants, you don’t know what he wants, the villagers don’t know, nobody knows. But if he’s anything like a human being, whatever he wants isn’t necessarily what he should have.” “Yes but, you said that–” “Forget what I said!”) The local Native American wise-man (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest‘s Will Sampson) is more straightforward: “The monster’s message to us is clear. We must send him Nolan or he will torment this village without mercy.” It’s only when the orca sets fire to the local industrial sector and blows its factories to pieces, then collapses Bo Derek’s house into the sea and bites off her aforementioned limb, that Nolan realizes he must stop listening to Charlotte Rampling – she was in Zardoz, after all – and sail out to face the whale.

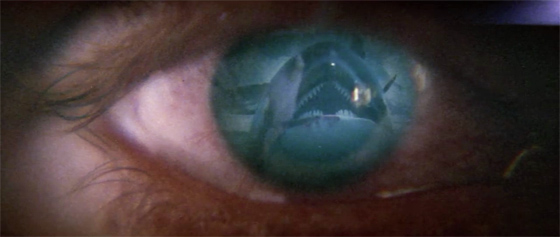

Orca prepares to feed.

Here Orca finally switches into Moby-Dick mode, as Harris transforms into Ahab and northward guides his crew – including Rampling, Sampson, Peter Hooten (The Inglorious Bastards) and Robert Carradine, until Carradine gets swallowed just like Wynn. The Bumpo keeps following that fin on the horizon until icebergs surround them, and they run short on fuel. The increasingly gaunt Harris begins to tackle dialogue like, “He loved his family more than I loved mine. I won’t be needin’ [a harpoon]. It’s got to be a fair fight, on equal terms.” Whatever that means; a few scenes later and he’s firing a rifle at the whale while balancing on an ice floe that the orca shoves around with its nose, all while Rampling watches from the edge of the set, dressed now like Obi-Wan Kenobi (as if to remind the audience of the film they could be watching next door). The set, actually, is quite impressive, as is much of the oceanic scenery once Orca moves into its final act. None of this – not even Harris’s Irish charm and 100% investment in his character – can rescue the film from the inescapable silliness of the endeavor. The screenwriters seem to be aiming for the same level of operatic emotion they achieved with Leone in the spaghetti western; but absent of Leone and any real style to speak of, and applied to the more lowly cinematic realm of “Jaws rip-off,” the task seems more Quixotic than Ahab-esque. Orca is worth seeing, none the less, for even if Dino De Laurentiis’s stamp isn’t a guarantee of quality, the promised spectacle is delivered – more than enough to overwhelm your feeble human brain.