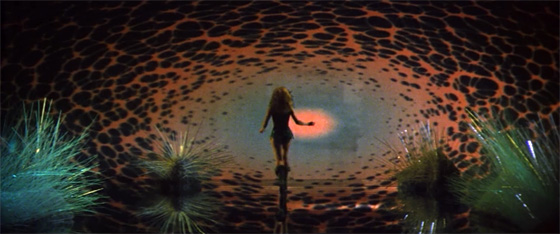

My first viewing of Barbarella (1968) was held to commemorate the purchase of a lava lamp, which, in retrospect, was ideal, because the film seems to exist inside of one. Roger Vadim’s science fiction spectacle is at its grooviest when it fills out its backgrounds with psychedelic light shows akin to those that were projected behind bands like Jefferson Airplane and Pink Floyd; there is a surreal loveliness to the scene in which Barbarella (Jane Fonda) strides through the “Chamber of Dreams” of the Black Queen (Anita Pallenberg), with the walls, floor, and ceiling reflecting colorful, swimming, abstract shapes. Here is a fine example of the inventiveness and charm of the pre-CG era. On the other hand, much of the film takes place on sets that look like they’re on loan from one of the lesser episodes of Star Trek. Barbarella flaunts its “contemporary” style and has a distinct sense of fashion, with “It” girl Fonda as its figurehead, but this means that her spaceship is bedecked with shag carpeting at all angles (with Seurat’s famous A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte filling the only un-carpeted wall), and the soundtrack is just as lounge, with the forgotten band The Glitterhouse crooning dated numbers like the title track: “It’s a wonder, wonder woman, you’re so wild and wonderful, ’cause it seems whenever we’re together the planets all stand still…Barbarella, psychedella, there’s a kind of cockle shell about you…”

Barbarella (Jane Fonda) receives her mission from the President of Earth.

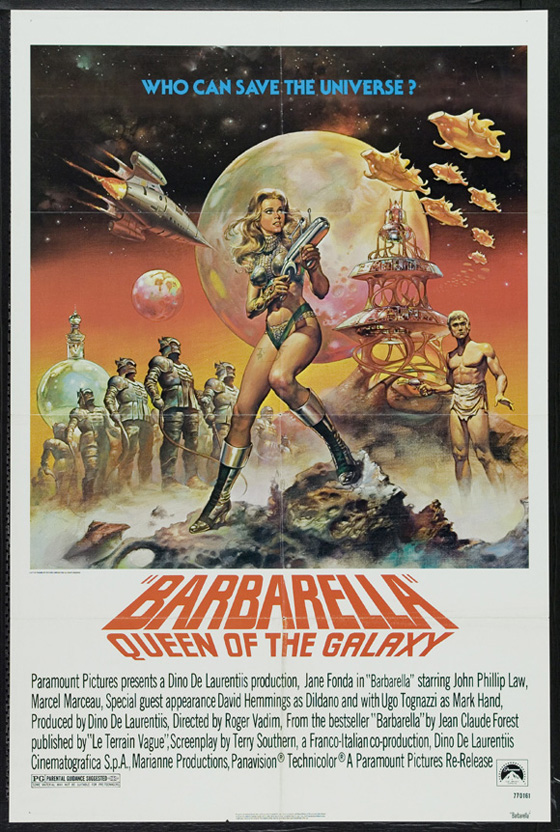

That kitschy spaceship becomes a kind of visual representation of the time capsule that Barbarella is. And, in my stranger moods, I wish that certain films could become literal time capsules – that they could be deliberately lost for a few decades so viewers can unearth them and appreciate them in a different way. Think of the caché El Topo (1970) gained from inaccessibility before it was finally released on DVD. Barbarella suffered the opposite fate: overexposure (pardon the expression). Due in no small part by Jane Fonda’s presence in the film – and her opening striptease, crafted by opening titles maestro Maurice Binder – Paramount has kept Barbarella in the public eye fairly consistently over the decades, exploiting its value as a cult item in spite of its initial box office failure. The poster art, an awesome and eye-popping design, was a common sight on video store shelves in the 80’s, and it wasn’t too surprising to see that the film was recently issued on Blu-Ray. But think of encountering this film knowing little to nothing about it, and encountering: the zero-gravity striptease, the pre-Sleeper jokes about antiseptic future sex, the bizarre props, the dream-like sets, the angel and sexual object Pygar (John Phillip Law), and the Excessive Machine, which the villain Durand Durand (Milo O’Shea) uses to assault Barbarella, before her own, liberated sexual energy destroys it. Is the film flawed? Absolutely. But for a moment, appreciate that this film was ever made in the first place.

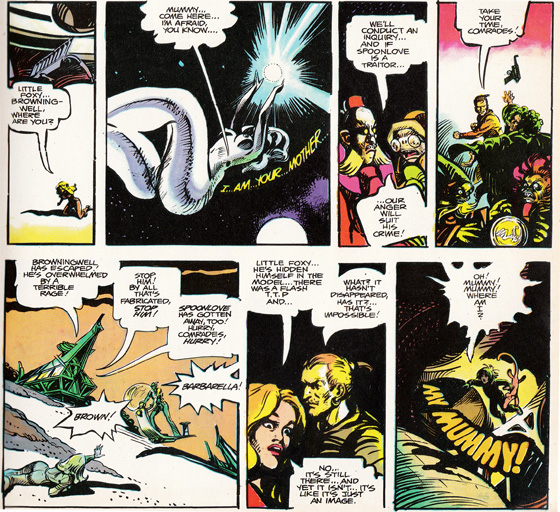

Excerpt from the "Barbarella" comic by Jean-Claude Forest, as reprinted in 1978 by "Heavy Metal."

It was an adaptation of an influential French comic by the talented writer/artist Jean-Claude Forest, a mix of high-concept science fiction and playful, comic eroticism: really, the perfect choice for the age of the sexual revolution and the rise of European cinema over waning Hollywood. The screenplay credits Forest as one of its “collaborators,” along with an alarming number of names, including Claude Brulé (who co-wrote Vadim’s Les Liaisons dangereuses 1960), the novelist Clement Biddle Wood, Tudor Gates (The Vampire Lovers), and others; but the principal writers are credited as Vadim and Terry Southern, the noted satirist who wrote the novels The Magic Christian and Candy, and who had worked on the scripts for Dr. Strangelove (1964) and Easy Rider (1969). Seeing all these names in the credits almost announces the film as a “happening”; Barbarella is not so much written as thrown together by some fashionable friends over drinks. As for Vadim, he would never find as big a project, but his best films – including the Brigitte Bardot-launching And God Created Woman (1956) and the genuinely poetic Blood and Roses (1960) – were all behind him. Increasingly, he was becoming famous not for his art but for the women in his life: Bardot, Annette Stroyberg, Catherine Deneuve, and now Fonda.

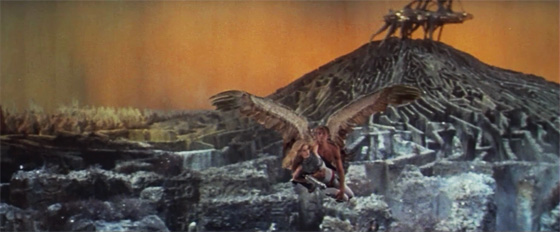

Pygar (John Phillip Law), rejuvenated by Barbarella's sexual energy, flies with her above the Labyrinth of the City of Night.

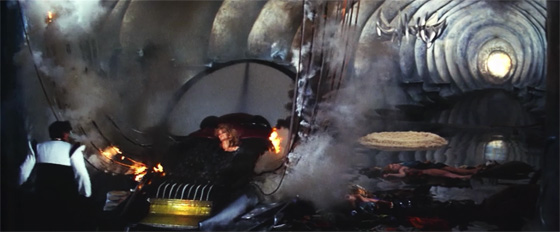

But Fonda was the oddest fit in the Vadim universe. As an actress (in films like 1965’s Cat Ballou and 1967’s Barefoot in the Park), she radiates wit and self-awareness. Vadim wrote in 1975 (in Memoirs of the Devil): “She did not enjoy shooting Barbarella at all. She accepted the part because I was very eager to make the film, but she disliked the central character for her lack of principles, her shameless exploitation of her charms and her irrelevancy to the political and social realities of the day…For her, Barbarella was the prototype of woman as an object. Today she still looks back on the part as a detestable symbol of woman’s status in a society of male oppressors.” Fonda saw the women’s lib side of the sexual revolution; Vadim, at his best, saw it as an acknowledgement that women had sexual desires just as men did, and his films embraced guilt-free consensual sex. Barbarella is not too different from those clumsy, major-studio, hippie-oriented cash-ins like I Love You, Alice B. Toklas (1968), but it benefits from having a female lead, and time and again reiterates that Barbarella’s newly-discovered physical sexuality (as opposed to the pill-popping kind she enjoyed on Earth) is her true superpower: with it, she can teach an angel how to fly again, and she can destroy the Excessive Machine with her orgasm. Perhaps Fonda was not as politically invested in the film’s ultimate message, which is that women can have orgasms too.

Barbarella uses her sexual energy to destroy the Excessive Machine of Durand Durand (Milo O'Shea).

As a story, it’s a sloppy affair, and the diffuse efforts of the multitude of screenwriters leave a script with lots of talking and very little coherency. Here, it helps that Fonda delivers her dialogue as though she’s doing Neil Simon again, but the words are a tangle of nonsense regarding a Positronic Ray and the Black Guards and “The Mathmos.” Essentially, the film is as camp as the 60’s Batman TV series, and this approach means it has much in common with the 1980 Flash Gordon, just as its softcore-comic elements link it to the 1974 Flesh Gordon. Camp is fine, but some stronger jokes would help. More deadly is the pacing: the film just keeps lumbering forward from one scene to the next with very little narrative momentum. But there’s a lot here that sticks, and makes the film worth seeing at least once. The bizarre Labyrinth that climbs up a mountain, with its residents wandering the passages like zombies, or partially-absorbed into it (freeze-frame the film to appreciate some very creative makeup work), resembles a surrealist painting. The interiors of the palace of the Black Queen are full of sexual decadence and abstract design. And placing angel wings on a bare-chested John Phillip Law proves to be both the simplest and the most effective special effect Barbarella achieves. Remakes have been attempted and abandoned over the years, most recently by Robert Rodriguez. It’s futile to try to recapture something so rooted in its time, but I admit that I’d love to see someone try.