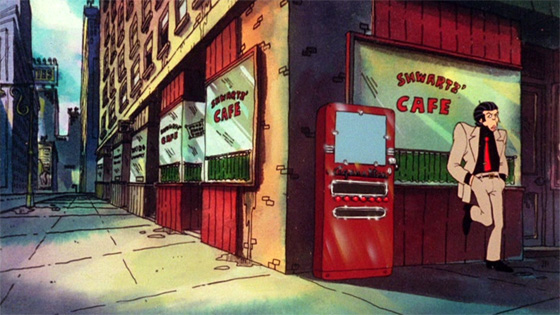

Finally available on DVD is one of Ralph Bakshi’s more obscure animated films, Hey Good Lookin’ (1982), his R-rated, semi-autobiographical reflection on street life in 1950’s Brooklyn. It’s a personal enough film to complete an informal trilogy begun with Heavy Traffic (1973) and Coonskin (1975), and though I still find both of those films to be superior, a revisit to Hey Good Lookin’ had me realizing this was a better film than I’d remembered, and a worthy capper to his earlier work. The plot is more of a hastily-scribbled sketch. Vinnie (Richard Romanus of Mean Streets and Heavy Metal) is an Italian-American greaser obsessed with his personal style and cool. His best friend is “Crazy” Shapiro (David Proval, also of Mean Streets, and later The Sopranos), a redheaded, Jewish, mouth-breathing personification of the Id. While Vinnie is reserved and smooth, Shapiro is loud, awkward, and ultimately delusional. Vinnie’s girlfriend is Rozzie (Tina Bowman, aka Tina Romanus), whom Bakshi’s animators relish drawing of such proportions that she threatens to explode her top, and her best friend is the plump and shy Eva (Jesse Welles, Wizards‘ fairy Elinore), whose passion for sandwiches rivals Wimpy’s for hamburgers. Over the course of a day and night, Shapiro’s antics lead Vinnie into deeper and deeper trouble, as he insists that Vinnie lead his gang the Stompers into a rumble with their black rivals, the Chaplains. The 50’s story is framed by the present, as a gravel-voiced stranger narrates to a middle-aged woman broken by some mysterious tragedy.

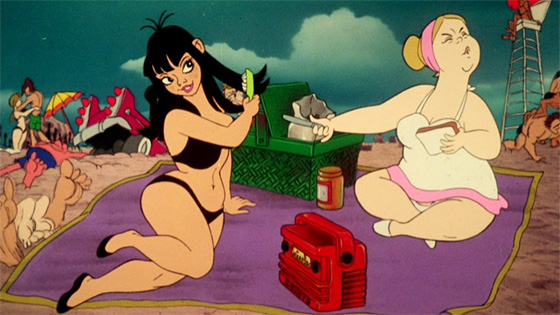

Rozzie and Eva at the beach, talking about boys.

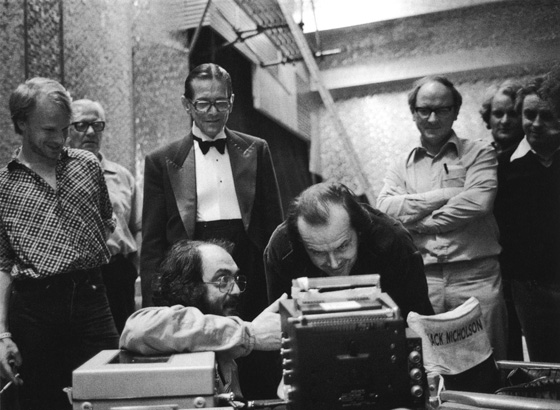

The film was released marginally and reluctantly by Warner Bros. in October of 1982, and it seems oddly placed in Bakshi’s filmography, squeezed between the epic statement of American Pop (1981) and the grim-faced sword & sorcery of Fire and Ice (1983), both of which built upon The Lord of the Rings‘ (1978) technique of filming as much as possible in live action before applying animation. If the (mostly) rotoscope-shunning Hey Good Lookin’ seems to belong more to his early 70’s output, there’s a good reason. He completed his first cut of the film in 1975, and reportedly it was a very different movie. Bakshi had been experimenting with mixing animation and live action since his first film, Fritz the Cat (1972), and took it to stylistic (and visually stunning) extremes with Heavy Traffic and Coonskin. Increasingly, live action took a larger role in his films, such that Coonskin featured live action framing scenes in homage to its inspiration (and satirical target), Song of the South. Hey Good Lookin’ was to be dominated by live action, with animated characters intruding into the real world, a proto-Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Stills from this unreleased film are included in the book Unfiltered: The Complete Ralph Bakshi by Jon M. Gibson & Chris McDonnell, which also reveals that one of the scenes featured a performance by the New York Dolls (!), and that the original soundtrack drew from Bakshi’s own vinyl collection.

A violent rumble climaxes the film.

But the film’s fate was affected by fallout from Coonskin – a picture that was passed from a balking Paramount to a smaller, less-reputable distributor when Al Sharpton and the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) protested the film’s content and questioned its intentions. With Hey Good Lookin’, Bakshi suddenly found himself with a completed film that no one wanted to release. True, the film had racial elements, but hardly of the powderkeg variety of his earlier picture. Hey Good Lookin’ features a black gang, and Vinnie makes a racist crack at one point – mainly to get a rise out of the gang’s leader – but, as with Heavy Traffic, the writer/director is aiming at gritty realism; pointedly, the film’s most shocking moment is the sudden and violent murder of two black men, and Vinnie becomes the audience surrogate when he feels sickened and outraged. Ultimately, Bakshi moved on to Wizards, and cult movie fans are forever grateful. But he wouldn’t let go of Hey Good Lookin’, and financed its completion, now as a fully-animated film (I presume that the film’s single, out-of-place rotoscoped sequence, involving the Chaplains striking poses in the street, is animated over some of the original cut’s live action). When the film was finally released, it suffered only slightly from the revision: the original songs, by Ric Sandler, have aged poorly, and one misses the stellar (and more expensive) soundtrack of American Pop.

The supporting cast are disproportionate caricatures, designed by the talented concept artist Louise Zingarelli, whose drawings were featured in the opening credits of "American Pop."

On the other hand, the hand-drawn animation has aged very well, particularly when viewed in the twenty-first century, when the craft is an endangered species. Bakshi weds memories of his Brooklyn youth to the beautiful grotesques of artist Louise Zingarelli, whose drawings were featured in the opening credits of American Pop. He embraces Zingarelli’s character designs, big-headed, oddly proportioned, saggy or scrawny, the weight of reality pressing upon them. Her style is most memorable with the image of the gangsters’ wives undressing on the beach, squeezing their flesh into their swimsuits, a celebration of the body at its most comically unlovely. At the other end of the spectrum, there’s Rozzie, whose enormous breasts are often placed prominently in the frame; “I’ll let you squeeze my tits,” she purrs at Vinnie, fully aware of her greatest currency among these teenagers. She’s the doe-eyed prize in tight jeans and tight tops to be delivered to the coolest and the toughest of all the greasers, but Bakshi’s just setting up the denouement, in which we see her in unglamorous middle-age. We may be hot stuff when we’re young, but we’ll all be Zingarelli drawings in the end.