Bram Stoker has achieved literary immortality, but his other supernatural novels are frequently forgotten or ignored. This is understandable, as none can touch the greatness of Dracula; yet I have a certain soft spot for The Jewel of Seven Stars, his 1903 novella of Egyptian mysticism, reincarnation, and murder, which was a precursor to Universal’s The Mummy (1932) and its series of spin-offs and rip-offs. The story is occasionally adapted for the screen by those who desire to toss Bram Stoker’s name into the advertising, but any link to the Count is misleading, at least on the basis of the somewhat staid source material. Mystery and Imagination, a British series adapting classic literary horror stories, took on the book in 1970 (they also adapted Dracula, and the series is available on DVD in the U.K.). It was inevitable that Hammer take a swing, but it’s surprising that it took the studio so long: it wasn’t until 1971 that they gave us Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb, begun by Seth Holt (The Nanny) and completed by Michael Carreras, offering a suitably dream-like version as well as the voluptuous Valerie Leon, in varying degrees of cleavage. In 1979 Universal revisited Dracula, ostensibly to adapt the hit stage revival with its star, Frank Langella; a big-budget production directed by John Badham, with Sir Laurence Olivier as Van Helsing, a score by John Williams, and some stylized sequences overseen by Maurice Binder of the Bond series, the film was hastily followed by a big studio Jewel of the Seven Stars adaptation that also involved Binder’s participation, plus Jack Cardiff (Black Narcissus) as cinematographer and a major star at the helm. That film was The Awakening (1980), but it was no monster mash.

"The Awakening": Egyptologists Matthew Corbeck (Charlton Heston) and Jane Turner (Susannah York) uncover the resting place of Queen Kara.

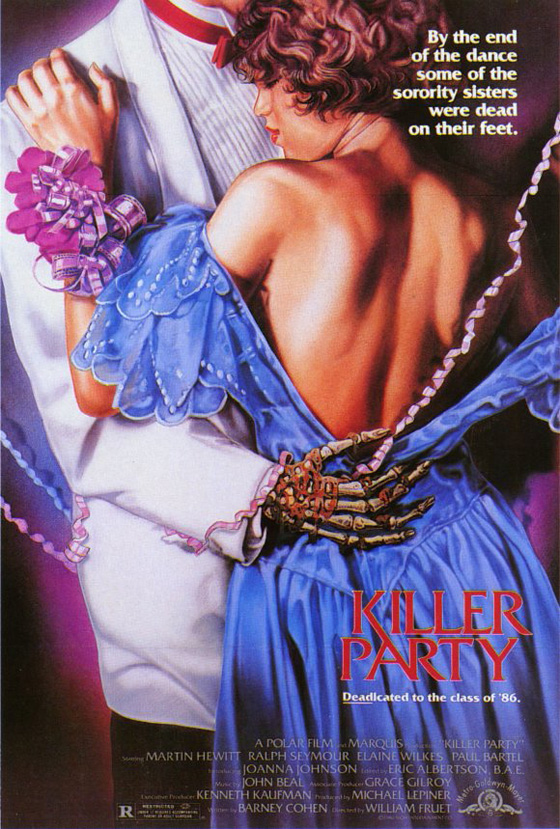

The poster for the film featured a wrapped-up mummy with glowing eyes and crossed arms below the tagline “They Thought They Had Buried Her Forever!” Anyone entering the theater expecting to see a female version of Christopher Lee’s stalking and strangling mummy would be disappointed. Instead, the film deploys its death scenes with stinginess – most occur in the last twenty minutes – and the traditional mummy icon makes barely a cameo. No, this is an adaptation of the Stoker story, reasonably faithful and what critics call “deliberately paced.” Director Mike Newell was graduating to the big screen after more than a decade in British television, with Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994), Donnie Brasco (1997), and Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2005) yet to come. He was given a major Hollywood star – albeit a waning one – with Charlton Heston in the role of Egyptologist Matthew Corbeck, obsessed with a dead queen named Kara, unaware that the woman’s spirit has occupied the body of his eighteen-year-old daughter Margaret (Stephanie Zimbalist, later of Remington Steele). The Awakening is heavy on omens and short on events; much of the film is simply Corbeck searching for the tomb, raiding it, and conniving to take as many of its artifacts as possible back to England. Stoker’s novel doesn’t follow the mummy-on-the-rampage plot dynamics of Universal or Hammer mummy sequels, and Newell doesn’t pander to those urges. When the deaths do commence, they are brutal but brief. It’s satisfying to see Margaret slowly overtaken by the spirit of the vengeful Queen Kara – a transformation the audience has been anticipating for a long while – but the ending is so abrupt that it’s likely to elicit nothing but frustration.

Heston prepares a ritual to resurrect Kara, while his possessed daughter Margaret (Stephanie Zimbalist) looks on.

Tellingly, two of the three credited screenwriters authored the Daphne Du Maurier adaptation Don’t Look Now (1973); it’s easy to imagine that Newell was going for a similar effect. Like that (superior) film, the focus is as much on the psychic turmoil of its central characters as it is the genre horror elements. The discovery of Kara’s tomb is told parallel to the dissolution of Corbeck’s marriage. The striking of the excavator’s pickaxe against the face of a cliff is cross-cut with the sharp birth pangs suffered by Corbeck’s wife; his entry into the hidden tomb occurs simultaneous to the birth of his daughter – which, significantly, he does not attend. It is made clear, visually and aurally, that the discovery of Kara’s sarcophagus draws her spirit out into the modern world, reanimating his stillborn daughter. When Margaret is grown, she exists such in Corbeck’s fearsome shadow that it seems natural she should transform into the object of his fixation, the dead queen. Though we know the history – that Kara was forced to marry her pharaoh father – it’s still unnerving to see Margaret plant an incestuous kiss on her old man’s lips. Incest and sins of the father become the main themes of The Awakening, though Stoker had other things on his mind. I enjoyed the atmosphere, Egyptian locations, and self-seriousness, but self-seriousness can only go so far. Stoker’s novel had a severed hand that killed, a sensationalistic detail that the 1980 version won’t touch. But sometimes a movie could use a severed murderous hand. For all the rigorous intellectualism on display in The Awakening (tomb = womb!), I’ll revisit the more shamelessly entertaining Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb more often.

The Lady Marsh (Amanda Donohoe) tempts Eve (Catherine Oxenberg) from a tree, in one of the many sly scenes in Ken Russell's "The Lair of the White Worm."

A completely different approach was taken for The Lair of the White Worm (1988), but one shouldn’t be surprised: Ken Russell was at the helm. Back in England after a brief attempt at working within the Hollywood machine (Altered States), he had lower budgets but as expansive an imagination as ever, as can be judged by this film and the same year’s delirious and wonderful Oscar Wilde tribute Salome’s Last Dance (1988). The Stoker source material was a 1911 novel in which the woman who moves in next door is revealed to be of an ancient race of giant shapeshifting snakes. In the book, a terrifically promising setup – an ensemble cast and a tactile sense of the eerie, a la Dracula – is undercut by an absurd and deflated ending. Russell seems to acknowledge the weaknesses. His Lair of the White Worm is a horror comedy that exists somewhere between Fright Night (1985) and Lisztomania (1975). He doesn’t try to convince the audience to believe in the reality of the supernatural elements, as Newell attempted; he wholeheartedly embraces the story’s ridiculousness with a very British wit.

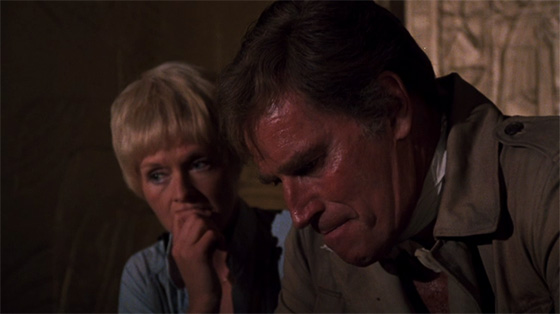

Lord D'Ampton (Hugh Grant) and Angus Flint (Peter Capaldi) discuss the matter of the local snake cult.

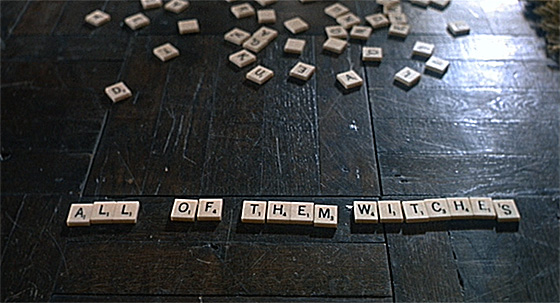

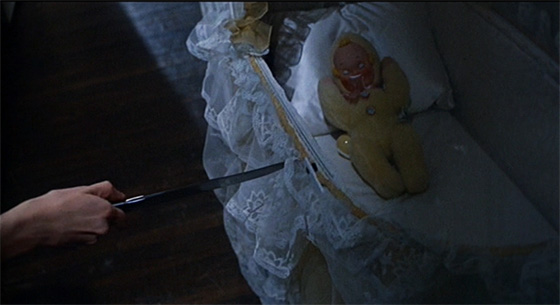

Amanda Donohoe (of Nicolas Roeg’s Castaway) is ideally cast as Lady Sylvia Marsh, a literal man-eater whose tight dresses accentuate her slinky wormishness. Investigating her suspicious behaviors are a group of young friends: Angus Flint (Peter Capaldi), Lord James D’Ampton (Hugh Grant), and Eve (Catherine Oxenberg) and Mary (Sammi Davis) Trent. The film opens with Angus’s discovery of a dragon-like skeleton in the ground – establishing the story’s connection between Russell’s blood-drinking villainess and the “worms” of old – and soon enough his cast are having blasphemous hallucinations using the kind of overheated Catholic/sexual symbolism Russell mined to such upsetting effect in The Devils (1971). Yet nothing is quite so serious here, as becomes evident by the time Marsh prepares to feast on a boy scout. While the boy is paralyzed by her venomous bite, trapped in her hot tub, she holds a dragon-skull above her head and launches into a speech about human sacrifice, only to be interrupted by a ringing doorbell and a muttered “Shit.” Snake references abound, from Donohoe’s stuffed mongoose to a scene in which she plays a game of Snakes and Ladders. While his friends go to investigate Marsh’s mansion, Grant blares snake charmer music from a record player to keep Donohoe mesmerized – which works, until the power goes out; a moment later Grant’s slicing of a vampire in two with his sword – meant to evoke his kinship with Sir George (and his dragon) – ends with him toppling over backward into a drumkit. Ultimately the film is a giddy romp – which is surprising, considering Russell’s pedigree of the defiantly unpalatable. Still, when he can’t resist costuming a topless Donohoe with a horn about her torso like a mock phallus during the climactic sacrifice sequence, it’s clear that he’s keeping obscene outrageousness within easy reach. This may not be Stoker, but as a midnight-movie cover of one of the author’s deeper cuts, it’s borderline brilliant.