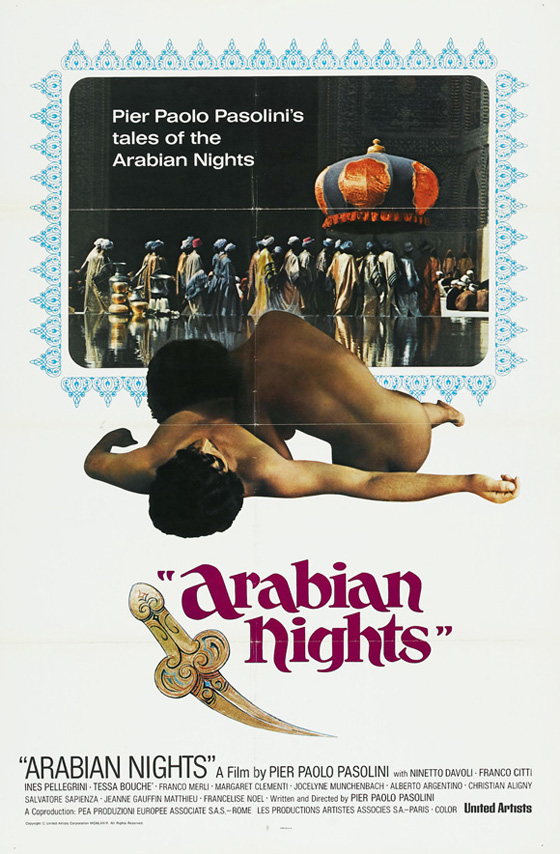

For me, these films were a gateway. I was living in Seattle, going to grad school, renting movies compulsively (it helped that I lived down the street from one of the best video stores in the country, Scarecrow Video). I saw Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Arabian Nights (1974) first; it was the last of a trilogy, though I didn’t know it at the time. I was merely interested in the Nights. When the film revealed itself to be a completely unconventional take on the book(s), I was taken by surprise: there is no Scheherazade to be found, no Aladdin or Ali Baba or Sindbad; instead, Pasolini tells lesser-known stories as they might have originally been told – from the point of view of commoners living in poverty – using a cast largely consisting of amateurs. What surprised me even more was Pasolini’s take on eroticism. His kind of Eros is earthy, matter-of-fact, and equal-opportunity with its nudity. It is not pornography, though all of his 70’s films were scandalous and tore down walls in their depiction of sexuality. What is transmitted through his “Trilogy of Life” is a rejoicing in humanity uncorrupted by the trappings of modern society. The most common recurring image in the three films is a close-up of a face smiling at or toward the camera. Pasolini was in love not just with the human body, but with people. (The director would ultimately submit to cynicism – but not yet.) Watching Pasolini’s trilogy renewed my interest in world cinema; I vowed that my tastes needed to be more adventurous, because there were many great works I might not otherwise encounter. When I had exhausted myself of Pasolini, I moved on to other directors; but rewatching these films for the first time in many, many years is not just nostalgia, but a revelation. The new Blu-Ray set of the films from Criterion is such a vast improvement over my old Image DVDs that it is truly like seeing them for the first time. (Note that some of the screenshots that follow are from the old DVDs, so don’t judge the visual quality from my images.)

"The Decameron": Caterina (Elisabetta Genovese) anticipates an evening with her new lover.

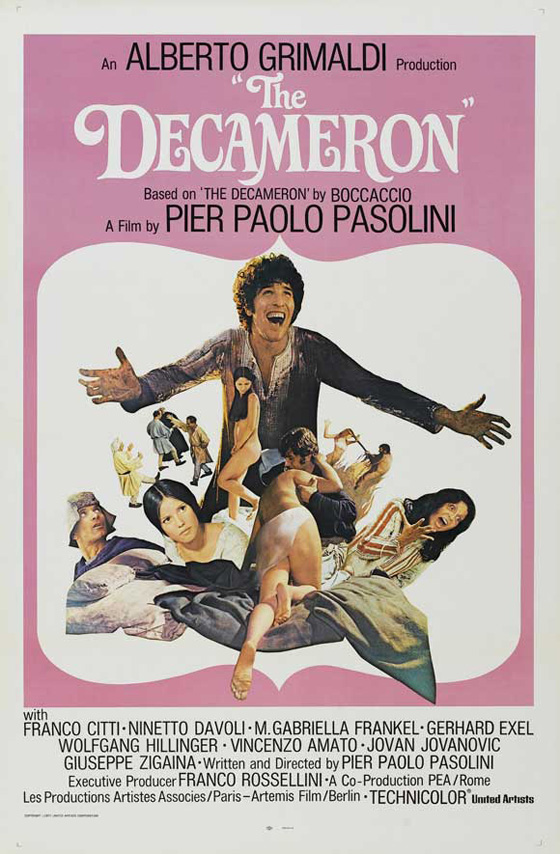

The highlight of the first film of the trilogy, The Decameron (1971) – adapted from the 14th century work by Giovanni Boccaccio – is a tale of young lovers (drawn from Day V, Book 4) that is the essence of simplicity. Riccardo wants to sleep with Caterina, though she is so closely watched by her father that they have never even spoken. One day, while she plays hide and seek with her friends, Riccardo steals a moment with her and confesses his love; she tells him that she will sleep on the roof that night, if he can climb to her. Then she begs her mother to let her sleep in the open air, for she is too warm indoors, and she wants to hear the nightingale sing. When her father rises early to see how she fared during the night, he finds her dozing naked next to Riccardo, her hand upon his penis. He hurries to wake his wife, crying, “Come see your daughter, who has caught the nightingale in her hand.” Their shock at the sight of the two sleeping lovers doesn’t last long; Riccardo comes from a wealthy family, so the scheming parents decide to exploit the situation by insisting Riccardo marry Caterina. The two are all too happy to marry, and the parents leave the couple alone, presumably to make love again. We are an hour into the film – we have grown accustomed to blunt nudity. To see, in a non-pornographic film, a young woman tenderly holding her lover’s genitals while she sleeps is no longer something that can raise eyebrows; instead, it’s easier to embrace the intent of the story. The moment is warm, joyous, and human.

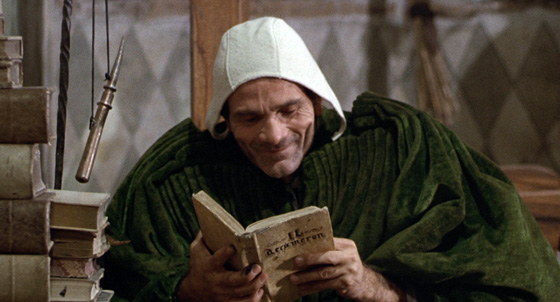

"The Decameron": Writer/director Pier Paolo Pasolini casts himself as a painter creating a fresco inspired by the townfolk of Naples. Here he studies the faces of the people in the same way that a director might craft his mise-en-scène.

Yet this approach was revolutionary, particularly coming from Pasolini. Pasolini was a poet, novelist, and essayist before he became a filmmaker, and his films of the 60’s are as aggressively, radically political as those of Godard. He was a Marxist, but was as likely to criticize the revolutionaries as he was the bourgeoisie. The Trilogy of Life does have antecedents in his filmography; he had already created adaptations of ancient works with one foot in Italian neorealism and historical accuracy, such as The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964) and Oedipus Rex (1967). Still, The Decameron marked a break from explicitly political films like Teorema (1968) and Porcile (1969); he was discarding his clothes and returning to nature. This new trilogy would adapt works that helped define the language of their respective cultures: Boccaccio, Chaucer, and the authorless tales of the Thousand and One Nights are all historical touchstones. Similarly, the films would allow Pasolini to recreate his own cinematic language. Fed up with the consumerist modern world, he wished to celebrate a simpler time when man’s chief concerns were love and death. By traveling into the slums and casting The Decameron with the faces he found there, he would place the peasant on a pedestal: a political statement, to be sure, but a clean and simple one. And if the text gave him ample opportunities to mock the Catholic church, all the better.

"The Decameron": Lustful nuns.

In The Decameron, one of the most outrageous sequences involves a peasant who pretends to be a deaf-mute to gain work inside a convent – and access to the women inside. He doesn’t need to bother with seduction; his manly presence is enough to give the nuns sinful ideas, along with the fact that he’s unable to confess those sins to anyone. When one of the nuns says, “But we promised our virginity to God!” the other responds, reasonably, “We’ve made lots of promises we don’t keep.” Subsequently the nuns are literally lining up to be deflowered, until, when the Mother Superior independently decides to seduce him, the overtaxed boy vocally complains. “It’s a miracle!” she says, quite aware that his newfound voice is no such thing. So he is venerated as a saint. This is about as efficient and funny (and cheerfully offensive) as one can render the familiar old “sinful nun” story. One thing that struck me on this viewing was just how explicit it was: at one point Pasolini pans down to the actor’s fully-erect penis, not a common sight in the movies. Thinking this was some new uncut version, I checked it against my old Image DVD. The shot was there, but it was so dark that you couldn’t tell what it was. So there’s an argument for high-definition for you.

"The Canterbury Tales": Chaucer's tales are given the Pasolini treatment.

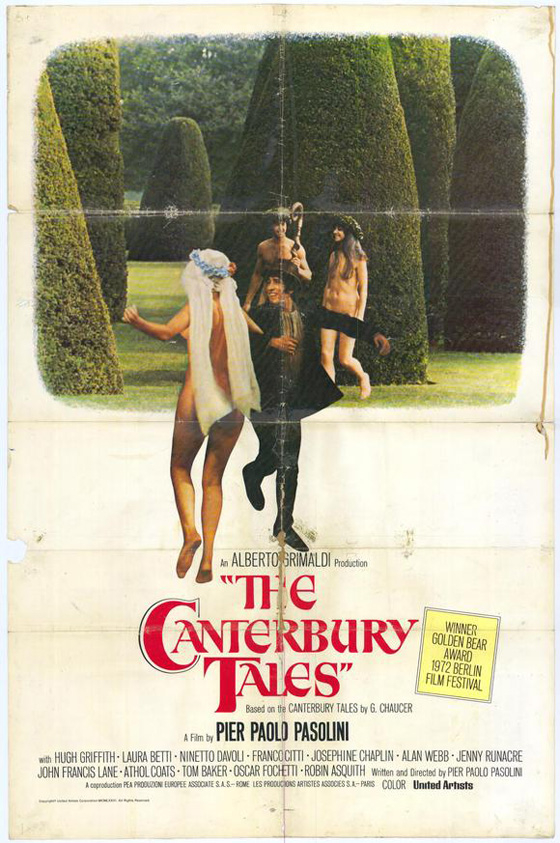

The Canterbury Tales is consciously a continuation of the trilogy, to the point that many of the same actors are used again, including Pasolini himself: in The Decameron he played “The Master,” a painter who was “Giotto’s best pupil”; in The Canterbury Tales he plays none other than Geoffrey Chaucer. In one scene, Chaucer is seen giggling over a copy of The Decameron in his study, a conceit that, one could argue, is historically possible, though unlikely. Could Chaucer read Italian? Well, in this version he can, because Pasolini transported his largely Italian cast to England to film amidst its castles and misty countrysides. Old English and Scottish folk songs are heard on the soundtrack (the score, as with all three films, is by Ennio Morricone), and some recognizable British actors are used, including one of the most popular incarnations of Doctor Who, Tom Baker, as a bookworm foil for the insatiably carnal Wife of Bath. (If you ever wanted to see a woman thrust her hand down the front of Doctor Who’s trousers, here’s the movie for you.) Hugh Griffith (Ben-Hur, Oliver!) plays Sir January, and fans of the Confessions series of films (Confessions of a Window Cleaner, etc.) will be treated to one particularly scatological scene featuring Timmy Lea himself, Robin Askwith.

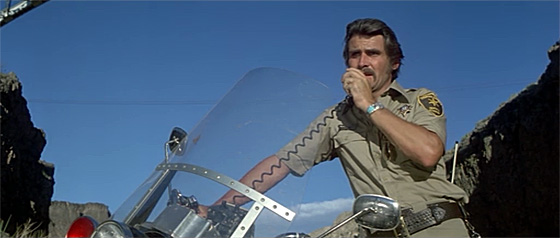

"The Canterbury Tales": Keystone Cops in 14th century England.

That scene, which involves a kind of baptism in urine, was one of the many reasons why Canterbury Tales turned me off when I first saw it; I was exhausted of crudity, and didn’t find the moments of beauty that I had seen in The Decameron and Arabian Nights. Revisiting it this time, particularly with Criterion’s presentation, my feelings were considerably more generous. A stylized slapstick sequence, in which Ninetto Davoli dons a Charlie Chaplin-like cane and bowler hat, is inventive, if not entirely effective. There are some amazing Dante Ferretti production design to enjoy, and colorful costumes straight out of medieval illustration. The final sequence – a blasphemous live-action fresco of Hell in which friars are ejected out of the ass of Satan – is at least memorable. Many of the crudest scenes, such as “The Miller’s Tale,” are in fact faithful adaptations of Chaucer’s bawdy original. Pasolini was now an anti-intellectual; he was in the business of making films for peasants, and on that level, the film succeeds as a valid interpretation of its source material.

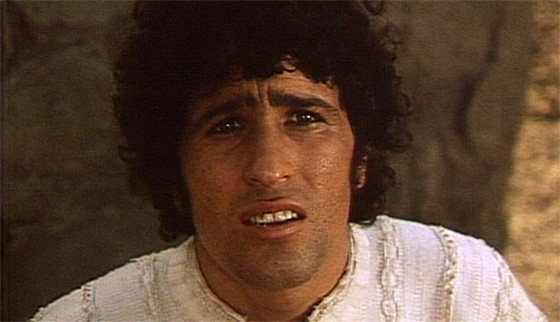

"Arabian Nights": Ninetto Davoli, the Fool of Pasolini's Trilogy of Life.

Davoli is the most prominent and recognizable face in the Trilogy of Life; he is its mascot, becoming a Tarot-like Fool in each of the films. After playing a reluctant, shit-stained graverobber in The Decameron, and performing a Chaplin impersonation in Canterbury Tales, it is in Arabian Nights that he receives his strongest showcase. He is Aziz, engaged to wed the humble Aziza, but who misses his wedding when he becomes fixated by a beauty he glimpses in a high window. Oblivious to the heartbreak he has caused, he seeks Aziza’s advice on courting this mysterious woman, who gives him strangely symbolic gestures from her high perch. Aziza interprets the gestures, and Aziz follows her advice and delivers the dialogue exactly as she has written it, though he doesn’t stop to consider the meaning: embodying the amateur actor of the type that Pasolini relished manipulating in his films. Only Aziz’s new lover understands when Aziza essentially writes her suicide letter through these verbal messages; but Aziz can still not properly decode this thing called emotion. It is only after he suffers at his lover’s hands – she has him held down and castrated – that he finally realizes how much Aziza loved him, and experiences true grief. Aziz, in this story, is not just a simpleton: he is a blank sheet of paper on which others inscribe their feelings. His tale can be a metaphor for many things, but above all else it is a primal folk tale, like so many in the Nights and those of Boccaccio and Chaucer as well; and the power in the story is in part because of how directly Pasolini tells it, with minimal adornment.

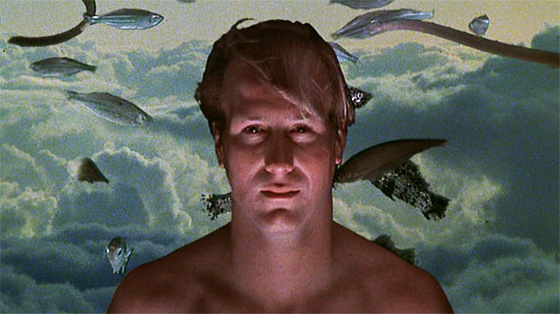

"Arabian Nights": Nur ed Din (Franco Merli) meets a lion in the desert.

Arabian Nights is the most visually spectacular of the three, as Pasolini filmed sequences in such diverse landscapes as Iran, Yemen, Ethiopia, and Nepal, like an anthropological research study of the stories’ origins. He wishes to strip the viewer of their presumptions about the text; this is not the storybook world that is seen in the two famous Thief of Bagdad films (1924, 1940) or The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958). He discards literature’s most famous framing story, instead telling the tale of a slave girl, Zumurrud (Ines Pellegrini), who is abducted and separated from her lover, Nur ed Din (Franco Merli), and eventually is mistaken for a king. While Nur ed Din searches for her, different travelers tell their histories (some of the “dervish” cycle of tales from the Nights are retold faithfully here), which weave together in unexpected ways. By this final film in the Trilogy of Life, Pasolini is so accustomed to this style of storytelling that he achieves a truly artful narrative fluidity. The viewer may occasionally be disoriented, but never for too long, and the charm of the original tales – along with Pasolini’s new ones – always shines through. He even, eventually, finds time for demons and magic, though he’s clearly uninterested in special effects. The fantastic is told as a kind of magical realism, similar to how angels, ghosts, and mythic beings casually intervened in the prior films. (In a metatextual in-joke, Franco Citti, who played a devil in The Canterbury Tales, plays another one here.)

"Arabian Nights": The palace where the slave-girl comes to rule, disguised as a king.

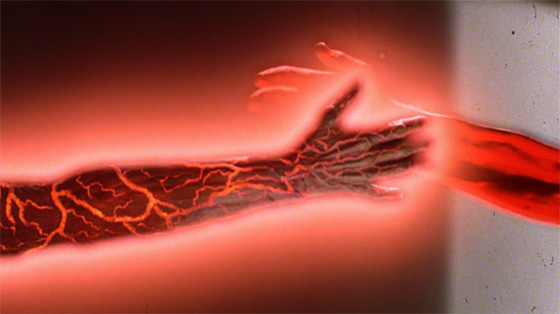

Watching the three films together and in order (or over the course of a couple of days, as I just did), one thing becomes clear: through the trilogy, Pasolini – who was gay – was becoming more daring with his depiction of the homoerotic. Though his camera’s loving gaze of uncircumcised penises is a recurring motif of the films, it is in The Canterbury Tales that he first directly addresses homosexuality: two gay men are exposed and accused, but only one is sentenced to death and burned alive – for he was too poor to afford a bribe to the Church-and-State. A brief scene in Arabian Nights in which an African man prepares to ravish three young naked fellows has no purpose other than to portray homosexuality as ordinary, and of equal weight to any expected Orientalist harem fantasy. So even this film is not entirely devoid of politics; the abundant male nudity, more prevalent here than before, is itself a reaction to the softcore and hardcore opuses that were in fashion in the early 70’s, most of them from a strictly heterosexual and male point-of-view (not to mention created with commercial, rather than artistic, intent). Today Pasolini’s use of nudity, both male and female, still feels radical; but then, cinema has in some ways become more sexually conservative since that burst of liberation in the 70’s.

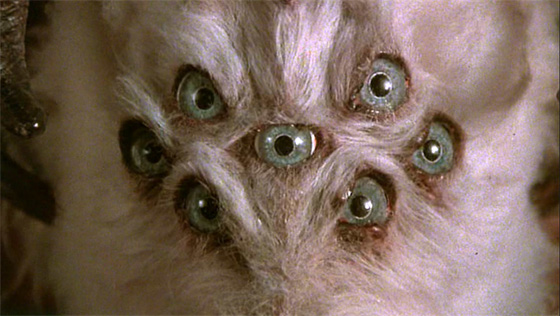

"Arabian Nights": A boy, transformed into a chimpanzee, demonstrates his writing skill.

Pasolini would subsequently “reject” the films with a famous essay that is thankfully reprinted in Criterion’s superb liner notes. Part of his reasoning was his loathing of contemporary Italian youth, which he now could not separate from the youth of the medieval past: “…if today they are human garbage, it means that they were potentially the same then,” he grouses. He no longer saw the human body as incorruptible, and would explicate with Saló, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), his final work before he was tragically murdered. In that still-shocking film, he condemns not just fascism (in the form of Mussolini’s government) but the bodies it exploits. No one, he decided, is blameless in their degradation of body and spirit. It was a grim final statement, but also something of a philosophical dead end, and one imagines that he would have gotten that out of his system, too, if he’d lived longer. Still, the Trilogy of Life is not diminished – not by Saló, not by the intervening decades following his death. The films remain a singular artistic statement, and for fans of Pasolini’s risk-taking cinema, the Blu-Ray set is invaluable.

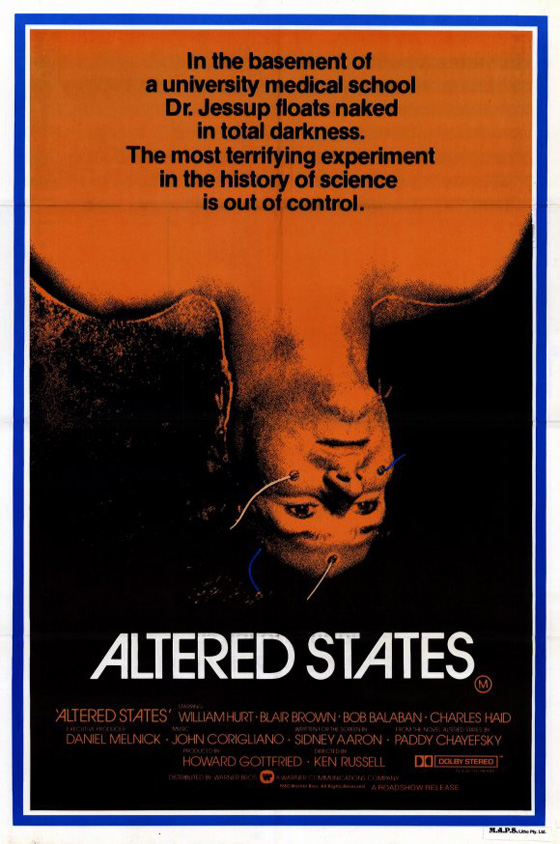

Arabian Nights