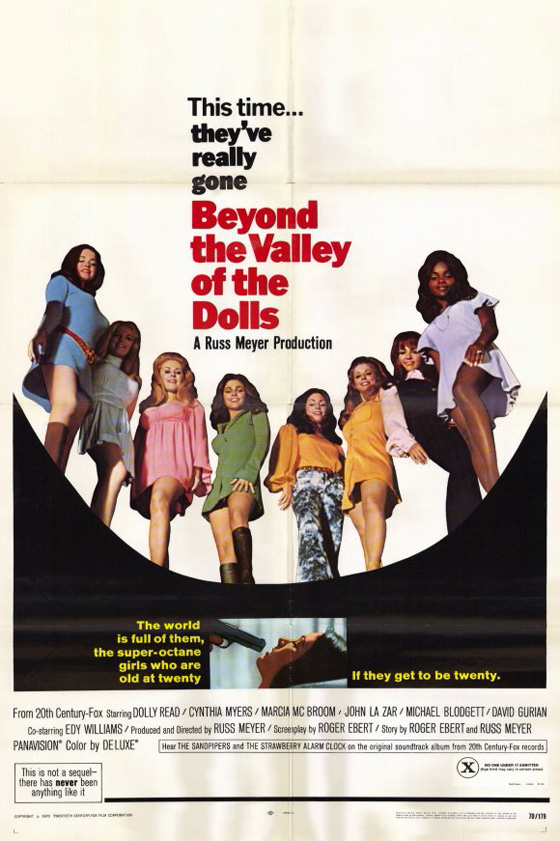

The late 60’s and early 70’s saw Hollywood studios flailing and gesticulating, desperate to catch the attention of an audience that was turning on to films like Easy Rider (1969) and Five Easy Pieces (1970), as well as the growing influence of world cinema, with its more risqué sex and challenging material. Old-fashioned, big-budget, all-star melodramas and musicals no longer clicked with audiences, and the studio system seemed to be in its death throes. As is well known – and mythologized – the decline of the studio system quickly paved the way for New Hollywood: Bonnie and Clyde (1967), The Graduate (1968), Francis Ford Coppola, Hal Ashby, Peter Bogdanovich, Martin Scorsese, and so on. But this era, particularly in its early years, also saw the release of confused, “I Have No Idea What You Kids Want” pictures like Skidoo (1968), with its pseudo-psychedelia and Groucho Marx playing a gangster called God, and Pretty Maids All in a Row (1971), which imported a French director (Roger Vadim) to present a sensationalistic exposé of high school promiscuity. (These films are being rapidly excavated as DVD distributors such as Warner Archive realize there’s an eager audience for them after all.) The well-endowed Queen of all these orphans is without a doubt Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970).

The (fake) Carrie Nations perform with the (real) Strawberry Alarm Clock.

Twentieth Century Fox had noticed that an independent softcore skin flick called Vixen (1968), one of the first films to be rated X, had grossed millions of dollars – possibly as much as 15 million, if Meyer is to be believed – on a very small budget of $72,000; as Jimmy McDonough writes in his excellent Meyer bio Big Bosoms and Square Jaws, the film ran for fifty-four weeks at an Elgin, Illinois drive-in called the Starlite, and forty-three weeks in Chicago, which would place Meyer firmly in Roger Ebert’s radar. The film was the Blair Witch Project of its day. Although Fox could have easily produced low-budget skin flicks of their own – nudity is a pretty cheap special effect – the studio honchos must have recognized something special in Meyer. Perhaps it was the way Vixen busted taboos (Lesbianism! Incest!) while maintaining a certain cheerful innocence. Perhaps it was his miserly way with his budgets. Perhaps it was his speed: while Vixen was still raking in the cash, his next film, the delirious, Charles Napier-starring acid trip Cherry, Harry & Raquel (1969), hit the grindhouses. Or perhaps they simply didn’t want to waste too much time and thought in deciphering what made Vixen so unique from all other sex films – it is, after all, a deeply odd little firecracker – and just wanted to co-opt the talent. The studio gates opened, and Meyer delivered the contraband. Ebert would write on the film’s tenth anniversary, “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls seems more and more like a movie that got made by accident when the lunatics took over the asylum.” Of course, he was one of those lunatics, and is quite proud of the fact.

Ashley St. Ives (Edy Williams, whom Russ Meyer would marry) seduces Harris Allsworth (David Gurian).

Meyer contacted Ebert after discovering that the critic was a fan; fast friends, the director asked him to write a screenplay to fulfill the first of his three-picture deal with Fox. The studio intended to create a sequel to the 1967 hit Valley of the Dolls, based on the Jacqueline Susann novel about love, showbiz, and barbiturates. After aborted attempts to make a straight-faced sequel, the studio was open to a more irreverent take by Meyer & Ebert. They paid little attention during the production process. The laissez-faire approach meant that the screenplay, “written in six weeks flat, laughing maniacally from time to time” (Ebert’s words), was put before the cameras without modification, all of its lunacy intact. If anything, Meyer only added to the crazy, applying his increasingly avant-garde editing approach, whose rhythms at times achieve a strobe effect, and musical selections that form an additional layer of satirical comment, from Stu Phillips’ soap opera strains during moments of melodrama, to, most notoriously, the use of the Twentieth Century Fox fanfare to underscore a graphic decapitation. Though this is his big-budget break, Meyer doesn’t skimp on the expected RM motifs. There’s the presence of a German (Henry Rowland) who is implied to be the Nazi Martin Bormann, this being a peculiar running gag in the work of the director, who served as a cameraman during WWII (as to Rowland, he returned to the role of Martin Bormann in Supervixens and Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens). There’s the cameo by the amusingly grotesque “Princess Livingston,” who also appeared in Meyer’s Wild Gals of the Naked West (1962) and Mudhoney (1965). Meyer veterans Charles Napier and Erica Gavin (Vixen herself!) have significant supporting roles. And, of course, there’s the fact that nearly every actress looks like a voluptuous 1960’s Playboy bunny – an aesthetic the pin-up photographer helped create in his years working for Hugh Hefner.

RM breaks from his usual technique of rapid cross-cutting by overlaying his key characters into the same frame during a Carrie Nations musical number.

The story itself is so happily convoluted that it’s barely worth summarizing. Suffice it to say that a Josie and the Pussycats-style girl group, the Carrie Nations (named after the violent anti-alcohol crusader of the turn of the century), journeys to Los Angeles and succumbs to all the temptations of showbiz, embodied by greedy, leering lawyer Porter Hall (Duncan McLeod) and the Phil Spector-like impresario Z-Man (John Lazar), whose too-florid dialogue trips clumsily over its Shakespeare. Lead singer Kelly MacNamara (Dolly Read) navigates both manipulators on her quest to rock ‘n’ roll superstardom, and dumps her boyfriend (David Gurian) for a worldly Adonis named Lance Rocke (Michael Blodgett); while her bandmates Petronella (Marcia McBroom) and Casey (Cynthia Myers) struggle through relationship problems of their own. It’s a nice touch that the girls are doing drugs at the very start of the film; Hollywood just brings wilder dangers, as delivered through the fevered imaginations of Ebert & Meyer. Soon enough someone ends up in a wheelchair, and a drug-fueled costume party, set to Paul Dukas’ “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” leads to a few surprising same-sex couplings as well as grisly murder.

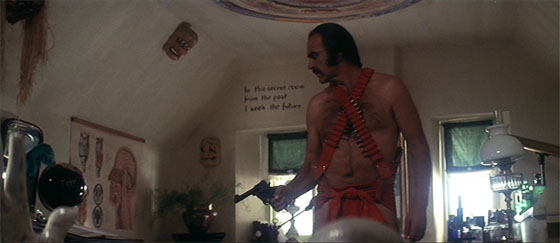

Z-Man (John Lazar) initiates a night of wild abandon.

Meyer was supposed to deliver an R-rated film, but was given an X instead (which he found frustrating, given how much X-rated material he’d forced himself to abandon to the cutting room floor). The movie was not a flop, though perhaps it was perceived as one, and most of the reviews were harsh, as critics saw tasteless trash instead of dead-on satire. One of the film’s harshest critics was none other than Gene Siskel. He panned the film upon its release, and when he gave it a second chance in 1993, lamented, “It’s even worse than I thought.” Meyer made only one more film of his three-picture deal with Fox, The Seven Minutes (1971) – an almost-forgotten movie on the (personal) subject of censorship – before embarking on the last phase of his career, returning to the life of an independent filmmaker, and turning up the sex and violence to even more cartoonish degrees. But Beyond the Valley of the Dolls was quick to discover a cult following, to the point that it is now one of the most popular of cult classics, and a frequent pick for revival screenings (including, naturally, at Ebertfest). It received a special edition DVD release from Fox as part of its “Cinema Classics Collection” (!), with supplements originally prepared for a Criterion release before Fox decided the film was good enough to call its own.

A "triple ceremony" gives the film an improbable happy ending.

It’s perhaps easier for more people to love the film now, with decades removed and the contemporary trappings providing an extra layer of amusement. For one, the songs (which Siskel hated) are actually a lot of fun, pastiches of psychedelic rock: vocalist Lynn Carey, whose voice Dolly Read lip-synchs, impressively channels her inner Grace Slick. (In one of the many head-spinning absurdities surrounding Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, a dispute with Carey’s managers resulted in a different vocalist appearing on the soundtrack LP. So the original LP is a singer not heard in a film which features a singer being dubbed by another singer. The CD, thankfully, has all the tracks you need.) The songs fit right alongside Strawberry Alarm Clock, who appear on-screen singing “Incense and Peppermints” and other songs, while Z-Man shouts the immortal “This is my happening, and it freaks me out!” – a moment to which Mike Myers paid homage in his first, and best, Austin Powers. There are many, many quotable lines here, which means the film requires multiple viewings so you can anticipate them with pleasure. And there’s so much crammed into this film that it impresses on each revisit: Meyer cuts so quickly, and Ebert’s plot moves so fast, that at 109 minutes Beyond the Valley of the Dolls features enough melodramatic incident to qualify it as a Gone with the Wind-style epic. Which it is, in a way – if only Scarlett O’Hara attended these types of parties.

The Carrie Nations perform while tragedy looms above.

But the reason I love Beyond the Valley of the Dolls is how it treats first-time viewers. It pulls the rug out from them slowly. It’s easy to laugh at the film as it begins, with the fake-hippie folk of “Come With the Gentle People” playing over the Carrie Nations’ fateful journey to L.A., and overcooked “youth” dialogue like “Hey, don’t bogart the joint.” But, if one’s not already attuned to it, it’s remarkable how the film gets nuttier and nuttier until the epiphany finally arrives that the filmmakers are in on the joke. They’re laughing (as Ebert said, “maniacally”) along with you. The climax has the John Waters aura of being quite contentedly beyond good taste, which means its spirit is aligned not with Jacqueline Susann but with the midnight movie, which it would ultimately become; and the denouement, with its triple wedding and villain Porter Hall glaring through the church window, could not make its comedy any plainer. I’m mystified when some classify this as a “bad movie.” To those standing in the church, it’s a rare and brilliant thing.