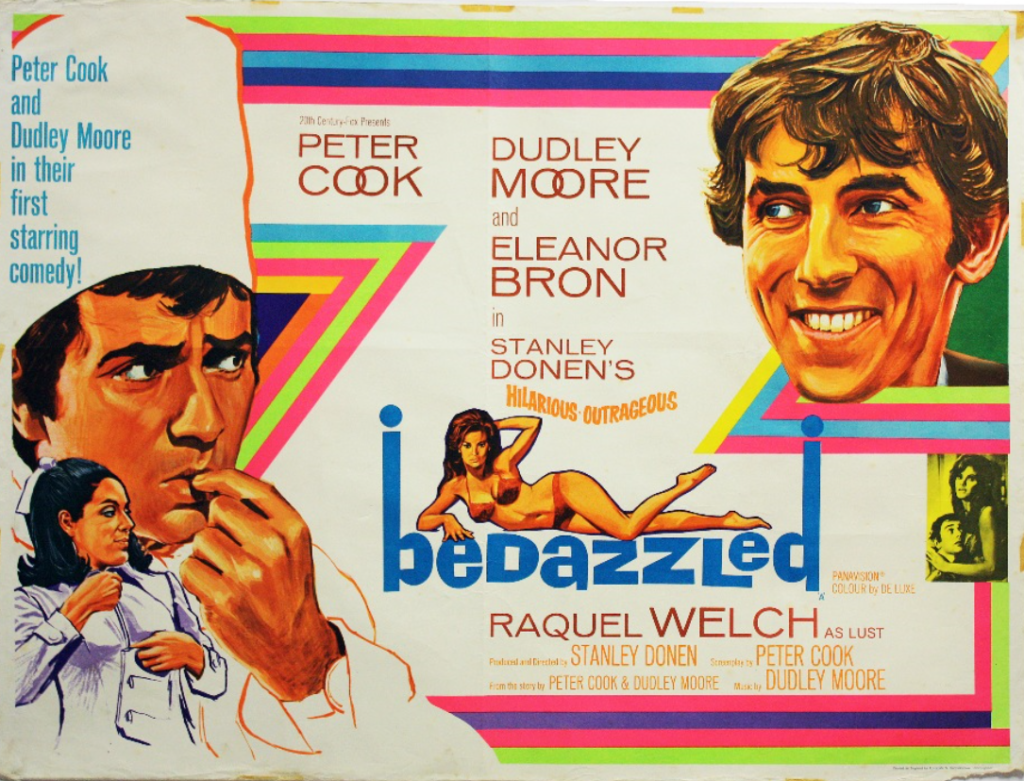

The exploding British comedy scene of the 60’s was fueled in large part by the breakthrough success of Beyond the Fringe, a theatrical revue with an emphasis on anti-establishment satire – both intellectual and unapologetically silly – featuring Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, Jonathan Miller, and Alan Bennett. All four young men achieved an instant celebrity, none more so than Cook and Moore, who starred in the series Not Only…But Also beginning in 1965, spotlighting their comedic – and, in the case of Moore, comedic and musical – talents. The two caught the attention of Stanley Donen, the legendary Singin’ in the Rain director who had moved to England in the early 60’s and recently completed two Hitchcock-inspired romantic thrillers, Charade (1963) and Arabesque (1966), as well as the experimental drama Two for the Road (1967), and he proposed a collaboration. The comedians subsequently conceived a modern variation on Faust, with Cook penning the screenplay and Moore composing the jazzy score, casting themselves as the leads (the Devil and his mark, respectively). It seems a small miracle that this film exists: a handsome 20th Century Fox production filmed in Swinging London and starring two stage-and-TV comedians who were unknown quantities as big-screen leading men. But the film played to the strengths of Donen, Cook, and Moore, with a significant comic assist by Eleanor Bron of Help! fame and a memorable supporting role – actually, hardly more than a cameo – from the film’s only true movie star, Raquel Welch. (Naturally, Welch was all over the advertising.) The late 60’s saw a number of oddball satires from major studios, but Bedazzled, with its clever dialogue and charming lead performances from three sketch comedy veterans, is easily one of the best.

Stanley Moon (Dudley Moore) attempts to seduce Margaret Spencer (Eleanor Bron) through a Satanically-assisted gift with words.

Dudley Moore gets a few letters swapped out to become Stanley Moon, a nebbish short-order cook who for six years (!) has been secretly, miserably in love with his co-worker Margaret Spencer (Bron). He can only bring himself to speak to her in his thoughts, and we eavesdrop on them as he opines: “Each time you speak it’s like a thousand violins playing in the halls of Heaven,” while waitress Margaret bleats deadeningly over the counter: “One cheeseburger, one shanty, one portion French fries.” In church, Stanley’s desperate prayer – apart from could he please get together with Margaret – is a request to God to give a little sign to prove his existence. (“I mean, I’m not saying that if you don’t give a sign I won’t believe in you; I’m not threatening you or anything like that…”) In answer he gets the Devil (Cook), currently using the pseudonym George Spiggott, who interrupts Stanley in the middle of a clumsy suicide attempt. He explains that he’s in competition with God to be the first to a hundred billion souls, and offers Stanley seven wishes in exchange for his. The first, a “trial wish,” he uses on a “Frobisher & Gleason raspberry-flavored ice lolly.” After taking a bus to the establishment, Spiggott hands him the ice lolly and asks, “Have you got a sixpence? I’ve only got a million-pound note.” Thus begins their exploitative friendship, with each of Stanley’s proper wishes coming with a monkey’s paw twist from Spiggott, who nonetheless washes his hands of all culpability.

Stanley Moon, pop star.

With one foot in sketch comedy, Bedazzled takes an episodic format based on each of Stanley’s wishes and the sexual frustration that ensues. He becomes a silver-tongued philosopher in my favorite of the segments, but Margaret’s erotically charged responses to his verbal gymnastics fails to translate into anything physical. Spiggott projects Stanley and Margaret into wealthy married life, but she’s blatantly unfaithful. And so on. These segments are kicked off with Spiggott’s reliable magic words “Julie Andrews” and end when Stanley blows a raspberry to communicate his desire to terminate (which seems to happen more quickly with each one). Donen gets to play with different modes for each outing, though the most notable stylistically is Stanley’s transformation into a pop idol, his in-studio performance filmed in black-and-white cinéma vérité and accompanied by dozens of screaming girls, offering not just a tribute to A Hard Day’s Night (1964) but verisimilitude with contemporary Top of the Pops-style programming. Stanley’s song, “Love Me,” needily pleas in thesaurus form, but he’s outgunned by Spiggott’s appearance as the placid-faced lead singer of Drimble Wedge and the Vegetation, whose song offers nothing to the audience but alternating loathing and indifference. “You fill me with inertia,” he tells his chorus of gyrating go-go dancers. While all this is happening, Margaret and an inspector with romantic intentions (Michael Bates) go searching for the missing, presumed-dead Stanley.

Raquel Welch as Lilian Lust.

The sketches are the film’s strength and its weakness; they tend to be one joke, escalated to conclusion – and you’ll get the joke pretty quickly. They also pad the film a bit unnecessarily; at 104 minutes, Bedazzled is pretty long for this simple a premise. But Cook’s screenplay finds plenty of hilarious moments between the sketches, filling in the details of Spiggott’s daily routine and illustrating how he’s become so jaded with it, eager to finish his game with God and win his way back into Heaven. He scratches records before sending them on their way (via a clothesline) to customers; he opens a box of Agatha Christie novels and tears out the last page of each. We also meet his retinue of the 7 Deadly Sins, including Welch as Lilian Lust – obviously Stanley’s personal favorite of the bunch – and Barry Humphries (Dame Edna) making a wonderful Envy. As the story progresses, and wish after wish crumbles, Stanley meekishly approaches a kind of low-key self actualization. Midway through the film he says that he likes Spiggott because he actually listens to him – which, naturally, is a double-edged sword. By the end of the film, he breaks free of Spiggott, and if this film is going to resonate with the viewer on a personal level, it’s the emotionally accurate depiction of an abusive relationship finally brought to an end. Stanley may never get with Margaret, but at least he’ll win or lose on his own small-scale terms. So Bedazzled is just as much therapy as it is devilish comedy, though the latter keeps giving and giving throughout the film. As when Stanley argues with Spiggott that Adam and Eve must have been happy in Eden, and Spiggott replies: “Of course they were. They were pig-ignorant.”