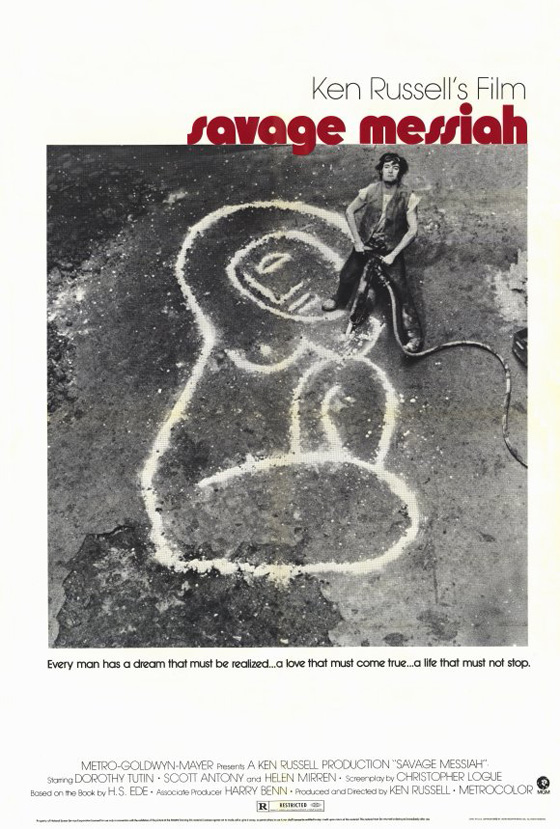

Savage Messiah (1972) charts the life of Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891-1915), a French sculptor and painter of the Vorticism movement whose promising career was cut short by tragedy. Most biopics have more decades of life from which to draw, which also flattens them, deadens their pace, encourages conventionality. Director Ken Russell must have been attracted to the life that burns twice as bright. In the early 1950’s Russell had read the biography Savage Messiah – written by an art gallery curator and collector of Gaudier’s work, H.S. Ede – and found inspiration in the tale of another struggling but recklessly passionate artist. After a string of notorious films which, if nothing else, put his name on the map and an Oscar nomination under his belt, Russell chose Ede’s book to adapt, largely self-financing this lower-budgeted project. He wanted to return to the scrappier methods of his BBC days. It was a wise move: Savage Messiah reminds critics that, when stripped of the distractions of opulence and sensationalism, Russell could still produce stunning works rich with emotion and energy. Once more, he perfectly channels the artistic spirit of his subject.

Henri Gaudier (Scott Antony) meets the older woman who will become the love of his life, Sophie Brzeska (Dorothy Tutin).

Ede’s work made special mention of Gaudier’s relationship with a woman twice his age, Sophie Brzeska, a Polish-born novelist. Though they never married, they were intensely devoted to one another: Gaudier took Sophie’s last name, and they lived together in Paris. Sexual relations were either minimal or non-existent, a fact that Russell runs with. “All Art is Sex!” screams the movie’s poster, in perhaps a desperate attempt to snare an audience, but it’s an honest assessment of what the film is about. Or what nearly all of Russell’s films are about. In The Music Lovers (1970) he depicts Tchaikovsky’s life through the filter of the composer’s repressed homosexuality, a tack which most critics did not appreciate. In Lisztomania (1975) he would portray Franz Liszt as a libidinous rock star. Savage Messiah deliberately refocuses the story of Henri Gaudier to a Harold and Maude story of love transcending a generation gap, as Gaudier and Brzeska connect over their shared passion for art, disdain for conventional society, and possible co-dependent mental illness. (Though the film ends its story in 1915, only ten years later Sophie Brzeska would die in a mental hospital.) We see Gaudier obsess over Sophie, but unable to possess her sexually, driven to prostitutes with her tormented approval. Note how Russell shows us these illicit encounters: we see nothing more than the prostitute disrobe and pose for Gaudier’s art. To be a life model, and to make it onto his canvas or into his sculptures, is akin to sexual consummation. When, late in the film, Sophie discovers that Gaudier has a new model, a sexy young suffragette (Helen Mirren, boldly delivering on the requisite Ken Russell nudity), she becomes distraught.

Gaudier in artistic ecstasy: "Enough stone for at least a fortnight!"

The film has its share of tour de force moments. Gaudier’s courtship of Brzeska in the opening scenes moves breathlessly, culminating in a confrontation in the Louvre staged like a castle battle, with Gaudier sitting upon a giant Easter Island head, tossing pages of his art at the spectators, while museum security approaches on what might as well be a medieval siege machine. “Now that, sir, is stone, and very valuable stone if I may say so,” says the museum attendant (played by Peter Vaughan of Brazil), “and if we let one visitor touch it, then everyone will be wanting to touch it.” “Art is alive!” rants Gaudier. “Enjoy it, laugh at it, love it or hate it, but don’t worship it – we’re not in church!” When, in Paris, Gaudier at last infiltrates a society of self-absorbed artists, he insists on challenging himself to produce a marble torso overnight to show to one of their wealthy exhibitors, Lionel Shaw (John Justin, The Thief of Bagdad). Gaudier steals marble from a cemetery. Then, in one long and mesmerizing sequence, he sets to work chipping at the stone throughout the night, sweaty, engaged, delivering a frenzied monologue while Sophie and their friend and champion, Angus Corky (actor, dancer, and mime, Lindsay Kemp), gradually drift off to sleep. By the morning, the torso is complete, but Shaw defers viewing it – so Gaudier tosses it through his gallery’s window. Art is All. When he discovers a beach with blocks of stone piled high, he climbs to the top in a fit of ecstasy – home at last, the possibilities for creation endless, liberating; while Sophie, isolated in her own frame, dances a solitary jig.

Gaudier finds a new model in Gosh Boyle (Helen Mirren), the free-spirited daughter of a wealthy army major.

Still, there are signs of restraint from Russell, who is more than content to let his actors take center stage this time around – or, more accurately, run from one side of the screen to the next, and leap before the camera and scream into it. (As my wife commented, there’s so much activity in the frame that you feel in constant danger of being run over.) This is a film which inherits certain attributes of the stage, with its literate screenplay by Christopher Logue; the wordy dialogue is conquered by the actors who simply charge straight through it as fast as they can, particularly the remarkable Dorothy Tutin (The Importance of Being Earnest) as Sophie, who flavors her monologues with a borderline schizophrenia. But she is a novelist, after all, and more comfortable turning inward than reaching outward. Scott Antony (Dead Cert) fails to hide his Britishness as Gaudier, but playing the young artist like an Oxford drop-out only suits the role. It’s unfortunate that he never made many films, given the talent on display here. Both came from the theater, and pitch their performances to the balconies, but this is precisely what Russell wants and knows how to use. By contrasting their performance style with those surrounding them – restrained, polite society – he demonstrates that these two live inside the madness of their artistry, disastrously so. Then again, you often see these types of performances in film musicals, a genre Russell so often embraced; Savage Messiah really plays like a musical without the songs (apart from an improvised one by Tutin). The eye-popping sets are by filmmaker Derek Jarman, who also worked on The Devils. This criminally overlooked film is one of Ken Russell’s best, and it’s available on DVD from the Warner Archive.