Monty Python’s Flying Circus ended its run in 1974 with something of a whimper: John Cleese had left the show by its final season, the title had been shortened to just Monty Python, and despite some moments of inspiration, the Flying Circus seemed to have met with a rough landing. Nonetheless, the release of Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) was on the horizon, and the individual Pythons were already moving on to some of their best solo work, notably Cleese’s Fawlty Towers. Eric Idle was one of the first out of the gate with Rutland Weekend Television, a Pythonesque sketch comedy series which can now be seen as a forerunner to SCTV. The program, which ran for two seasons and a Christmas special through 1975-76, has never been released on DVD, but spawned one of Idle’s best-loved creations, The Rutles. The fictional band, a send-up of the Beatles, were the invention of Idle and series co-star Neil Innes. Innes was a member of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, who had appeared in Magical Mystery Tour. He was also a longtime friend of Idle’s, the Bonzos having been the house band for the proto-Python series Do Not Adjust Your Set in 1968 with Idle as well as Terry Jones, Michael Palin, and Terry Gilliam; eventually he began appearing on Monty Python and touring with the group (he can be heard on the live albums, and seen performing in the concert film Monty Python Live at the Hollywood Bowl). Most famously, he played the doomed minstrel in Holy Grail. The Rutles were at first little more than a short film parodying A Hard Day’s Night; they were included in the tie-in The Rutland Dirty Weekend Book, and the song from the short film, “I Must Be in Love,” was included on the LP The Rutland Weekend Songbook. When Idle was asked to guest host Saturday Night Live – seen by many as the heir apparent to Monty Python – he brought along the Rutles film to help fill out the program. He told Kim Howard Johnson in Life Before and After Monty Python, “I had the idea to do it as a show for TV in England, and Lorne Michaels said ‘Hang on, I’ve got a larger budget at NBC – why don’t you do it for NBC, and you’ll get more money to spend?’ It seemed like a wise idea at the time…”

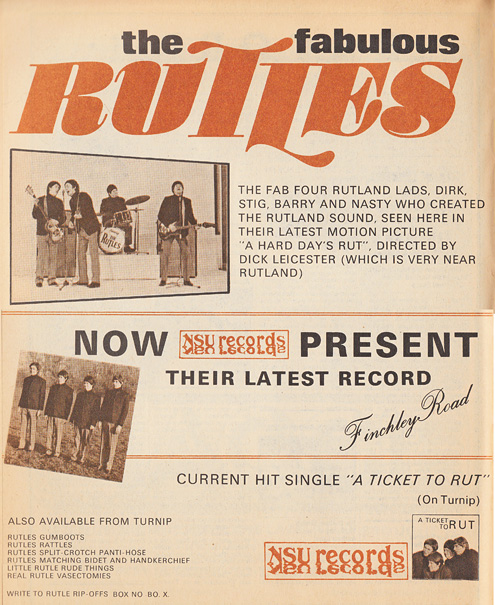

Fake advertisement for The Rutles from "The Rutland Dirty Weekend Book" (1976).

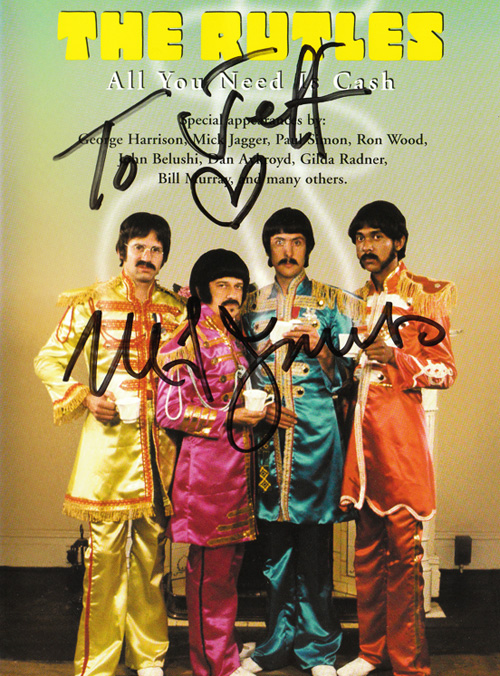

It was indeed a wise idea, for The Rutles: All You Need is Cash (1978) is now widely regarded as the best of the Beatles parodies, and the fake band has garnered a cult following of its own, to rival that of Spinal Tap. This television special (feature length: 73 minutes without commercials) takes as its scope the entirety of the Beatles’ career, each phase parodied with a geeky specificity. Although it’s not necessary to know anything about the Fab Four to appreciate the irreverent humor – Idle is also sending up pretentious documentaries – it probably doesn’t seem like a very remarkable film unless you’re up on your Beatles lore. That’s the thing: there are enough Beatlemaniacs in the world to justify pushing the gags into the obscure, like a reenactment of Cynthia Lennon being left at the train station while the Beatles headed off to Bangor for a Transcendental Meditation conference, or recreating the photos of Astrid Kirchherr while narrator Idle talks of the forgotten fifth Rutle, “Leppo.” Part of this exactness was the result of Idle and Innes having watched a rough cut of The Long and Winding Road, what was supposed to be the “official” Beatles documentary, but was never actually completed and released. (The project would eventually become The Beatles Anthology.) But of course there had already been countless books and articles published about the band, and the minutiae of their history was canonical to pop culture. The Rutles took that as a given, and included in its running time parodies of Beatles album covers, films, public scandals (including John’s “bigger than Jesus” remark, and Paul’s admission of taking LSD), and, of course, the songs themselves.

"Piggy in the Middle," part of the Rutles film "Tragical History Tour": "They say revolution's in the air/I'm dancing in my underwear/and I don't care."

Twenty original songs were composed for the film by Innes and performed with Ollie Halsall, Rikki Fataar, John Halsey, Andy Brown, and John Altman, covering the scope of Beatles styles from the early Hamburg years to their Let it Be rooftop performance. The soundtrack – released as an LP, and later an expanded CD – is so solid a rock album that Innes recorded a follow-up, Archaeology, in 1996. Innes’ vocals are uncannily like Lennon’s, to the extent that the Rutles song “Cheese and Onions” was once included on a Beatles bootleg in error. He plays the Lennon role of Ron Nasty in the film, mimicking his subject – irreverent, aloof – almost clinically. Idle is Dirk McQuickly; during a Royal Command Performance he captures Paul’s mooney-eyed gaze while singing the love ballad “With a Girl Like You” and locking eyes with a bored Queen. Musicians Halsey and Fataar play Barry Wom (Ringo) and Stig O’Hara (George), respectively, and Harrison was probably pleased to see he was being played by an Indian. Harrison – a Python fan who had appeared on Rutland Weekend Television, and would produce Life of Brian (1979) – cameos in the film as an interviewer questioning a Derek Taylor-like Michael Palin about the finances of Rutle Corps. It’s suggested that a company which gives away money for free might not be a good idea; while Palin carefully words his answers, looters run riot in the background.

George Harrison's cameo, with Michael Palin, outside the offices of "Rutle Corps."

Also here: Paul Simon, Ronnie Wood, Bianca Jagger (as Dirk’s wife Martini, “a French actress who spoke no English and precious little French”), and an impish Mick Jagger, who seems to relish taking shots at the Beatles through the thin veil of the Rutles: “About twenty minutes and that was it, off, helicopter, back to the Warwick Hotel, two birds each.” With Lorne Michaels producing and Gary Weis co-directing with Idle (Weis had made short films for SNL), a large segment of the SNL cast contributes to the film, including John Belushi, Dan Aykroyd, Gilda Radner, Al Franken, Tom Davis, and Bill Murray as “Bill Murray the ‘K.'” This SNL/Monty Python blend proves irresistible, the Pythonesque conceptual gags (Idle’s host is constantly vexed by the camera, which creeps away from him, transports him to the wrong locations, and even runs him over) mixing well with some 70’s late-night-TV edginess (Idle to Aykroyd: “What’s it like to be such an asshole?”). And it has to be said that Idle fearlessly approaches some awkward subject matter, such as Brian Epstein’s closeted sexuality and accidental death. But the latter, however dark, inspires one of the film’s funniest sequences: an interview with Stig and Nasty in which they react with shock to their manager’s sudden acceptance of a teaching post in Australia. Idle and Innes slowly process the advice of their new spiritual mentor, the Surrey Mystic: “We shouldn’t be covered with grief at thoughts of Australia.” “He did say we could still keep in touch with him by tapping the table.” “And postcards.”

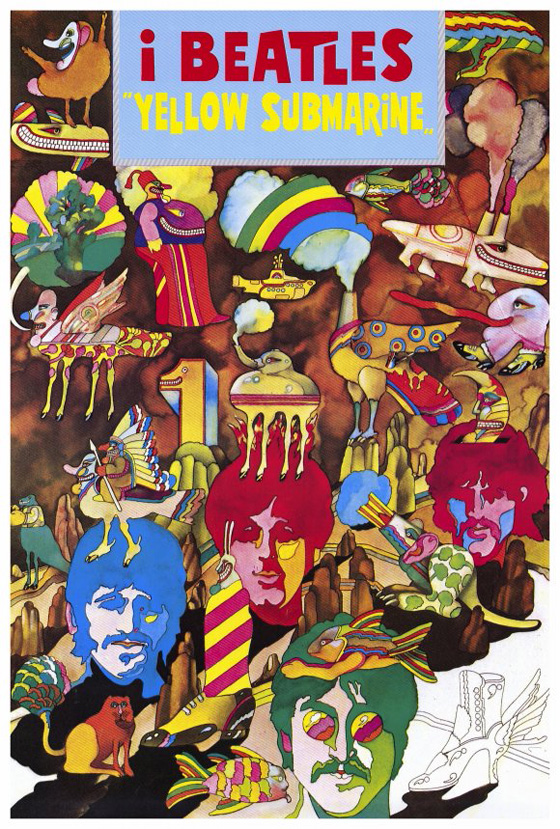

The "Cheese and Onions" sequence from "Yellow Submarine Sandwich."

Animators from Yellow Submarine (1968) actually worked on a short segment in The Rutles parodying the movie, which helps explain why the animation seems to move past the point of homage – it could almost be a deleted scene from the Beatles film. (Don’t miss that the song which plays over the animation, “Cheese and Onions,” has a droll musical send-up of “A Day in the Life” at the very end.) But it was the Rutles music that was accused of being too close to the source: ATV Music, then owners of the Beatles catalogue, sued Innes for 50% of the songs’ copyright – rather absurd if placed in light of the entire career of “Weird” Al Yankovic. Still, the Rutles legend endures through the two Innes-led albums and a sequel created by Idle, The Rutles 2: Can’t Buy Me Lunch (2005, compiled using outtakes from the original); but most of all through the enduring popularity of All You Need is Cash. Now, just as Python was often considered to continue the spirit of the Beatles, the Rutles seem to co-exist with the Beatles like the flip side of a coin. As Harrison wrote in his autobiography, I Me Mine, “The Rutles told the story so much better than the usual boring documentary. Try and see that film. That is a recommendation rather like saying: ‘Don’t bother me – see my lawyer. He will explain everything.'”