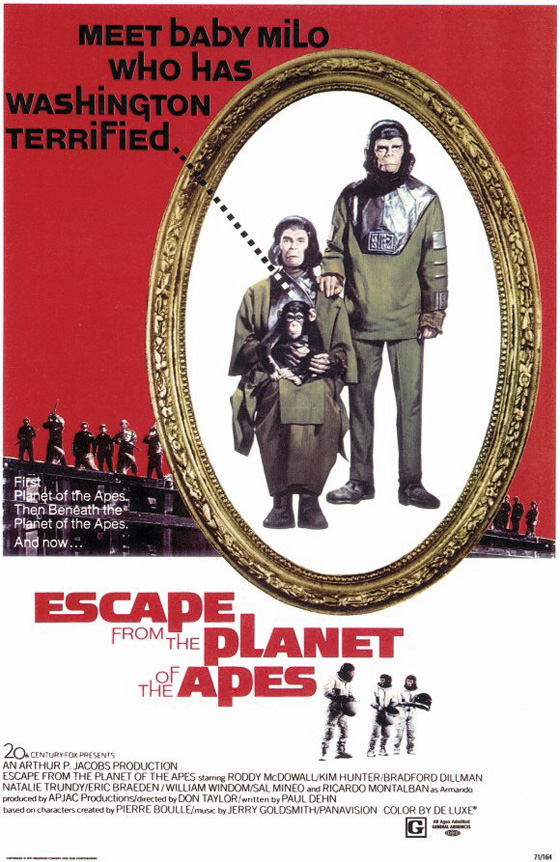

The third installment of the now-unstoppable Planet of the Apes franchise was something of a miracle baby, and it benefited from the unusual birth. When last we left the saga, in Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970), Charlton Heston’s Taylor had detonated a nuclear bomb which destroyed the entire Earth (and, the pressganged actor hoped, the series as well). But the series’ producer, Arthur P. Jacobs, couldn’t let something so financially lucrative burn to a cinder with the rest of the planet. He handed Beneath‘s screenwriter Paul Dehn the impossible task of writing another sequel, and Dehn found his answer by returning to the time-travel concept of the original film. Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971) would be both a sequel and a prequel, with three apes piloting Taylor’s salvaged spacecraft through a wormhole in time/space, a journey which takes them from the year “Thirty-Nine Fifty-something” back to the Earth of the 1970’s (1973, to be exact – this film took place two years in the future). The opening scene provides the film’s most clever moment: beginning with the camera gazing at high cliffs overlooking a chilly coastline, the audience presumes we’re once more revisiting the final scenes of Planet of the Apes (1968). But a helicopter cuts overhead – technology the apes didn’t possess. We see the familiar triangular spaceship floating in the water, and then a military convoy pulling up on the beach. Soldiers pull three astronauts from the ship. When the helmets are removed, the human onlookers are shocked to see three ape-men: Cornelius (Roddy McDowall), Zira (Kim Hunter), and a new character, Dr. Milo (Rebel Without a Cause‘s Sal Mineo). We’re back in the world of POTA, but as seen through the looking-glass.

The third installment of the now-unstoppable Planet of the Apes franchise was something of a miracle baby, and it benefited from the unusual birth. When last we left the saga, in Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970), Charlton Heston’s Taylor had detonated a nuclear bomb which destroyed the entire Earth (and, the pressganged actor hoped, the series as well). But the series’ producer, Arthur P. Jacobs, couldn’t let something so financially lucrative burn to a cinder with the rest of the planet. He handed Beneath‘s screenwriter Paul Dehn the impossible task of writing another sequel, and Dehn found his answer by returning to the time-travel concept of the original film. Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971) would be both a sequel and a prequel, with three apes piloting Taylor’s salvaged spacecraft through a wormhole in time/space, a journey which takes them from the year “Thirty-Nine Fifty-something” back to the Earth of the 1970’s (1973, to be exact – this film took place two years in the future). The opening scene provides the film’s most clever moment: beginning with the camera gazing at high cliffs overlooking a chilly coastline, the audience presumes we’re once more revisiting the final scenes of Planet of the Apes (1968). But a helicopter cuts overhead – technology the apes didn’t possess. We see the familiar triangular spaceship floating in the water, and then a military convoy pulling up on the beach. Soldiers pull three astronauts from the ship. When the helmets are removed, the human onlookers are shocked to see three ape-men: Cornelius (Roddy McDowall), Zira (Kim Hunter), and a new character, Dr. Milo (Rebel Without a Cause‘s Sal Mineo). We’re back in the world of POTA, but as seen through the looking-glass.

Zira (Kim Hunter) and Cornelius (Roddy McDowall) are interrogated by government agents.

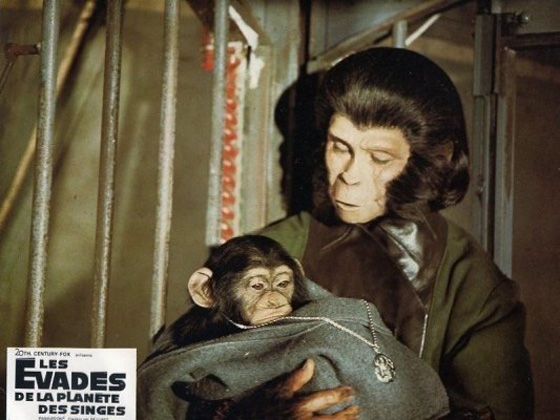

Dr. Milo doesn’t last long; when the “apeonauts” are taken to the Los Angeles Zoo for examination, Milo is strangled by a (jealous?) gorilla in the next cage over. Exit Sal Mineo – who was grateful, for he was uncomfortable with the makeup; the actor, who had been struggling to win big-screen roles, would never appear in a film again. The rest of the film is devoted to the interactions between humankind and the apes, now represented by McDowall and Hunter. Cornelius and Zira receive the greatest sympathy from Dr. Lewis Dixon (Bradford Dillman, The Mephisto Waltz) and Dr. Stephanie “Stevie” Branton (Natalie Trundy, “Albina” in Beneath the Planet of the Apes), but they’re regarded with suspicion by Dr. Otto Hasslein (Eric Braeden, now best known for his long-running role as Victor on the soap The Young and the Restless). Hasslein, who has the ear of the President (William Windom, Brewster McCloud), is one of the most intriguing characters of the film: brilliant but emotionally detached, he accepts the apes’ story but also penetrates its implications, namely the future subjugation of the human race by the ape-men. When it’s discovered that Zira is pregnant, he suggests the baby be aborted and the apes sterilized. Cornelius accidentally kills an orderly while escaping with Zira from the hospital; this leads Hasslein to the conclusion that they must be killed. Eventually he’s prepared to coldly gun down Zira’s squealing newborn, and yet you can never quite call him evil. He thinks he’s saving all humanity.

Lobby card: Zira cradles her newborn, played by a real (and probably really confused) chimpanzee.

Happily, this third installment returns to the fractured but philosophical tone of the original film: it’s alternately a satire, a thriller, a science fiction think-piece, a comedy of manners, and a downbeat message-picture. We’re stranded with the apes in a familiar landscape, but we see it through their eyes: absurd, overwhelming, but the civility just barely disguising a ruthlessness not too different from the world of the apes. Here, Cornelius and Zira enact the role of Taylor, and Dixon and Branton become their protectors, along with a late-arriving Ricardo Montalban as Armando, the ringmaster of a circus who shelters the apes so Zira can give birth in safety. (His over-the-top dialogue seems custom-written: “If it is destiny for Man to be dominated, oh please God let him be dominated by one such as you!” he tells Zira, as though she’s about to board a plane out of Fantasy Island.) Mirror-images of the original film are cast throughout Escape‘s running time, from a hearing in which the apes are asked to prove their intelligence, to a moment in a museum in which Zira nearly faints at the sight of a stuffed gorilla (the same moment we learn she’s pregnant). Some light satire is scattered through a montage of the two apes adjusting to the fast-paced Los Angeles scene, trying out the latest fashions, holding parties, indulging in a bubble bath for the first time, and being introduced to “grape juice plus” (wine). The change of venue does wonders for reinvigorating the franchise – this would turn out to be the middle picture in a quintet – but the modern setting inevitably renders the film more dated; even Jerry Goldsmith, returning as composer, provides a more run-of-the-mill score. But it’s hard to ignore how boldly dark the film becomes in its last fifteen minutes, as the apocalyptic themes of the series are enacted on a human level rather than a global one. Behind all the makeup and broad satirical strokes, the Apes series was never afraid to be confrontational with its politics. Dehn deliberately left room for a sequel this time, but also cleared out some space for even darker themes for the franchise to explore.