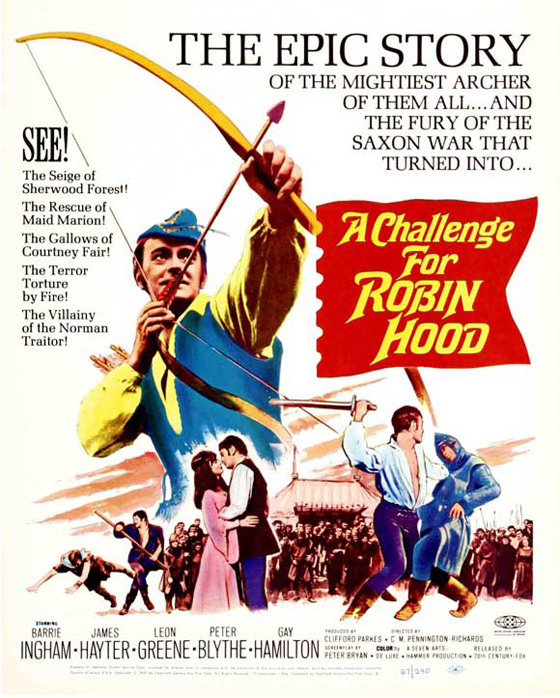

Hammer’s third go at the Robin Hood legend is something of a latecomer, there being a seven-year gap between this film, A Challenge for Robin Hood (1967), and their previous Sword of Sherwood Forest (1960). It’s what we would now call a reboot. The Terence Fisher film left Robin Hood betrothed to Maid Marian, and the villains, including the Sheriff of Nottingham, slain. Director C.M. Pennington-Richards (Black Tide) and screenwriter Peter Bryan (The Hound of the Baskervilles), ignoring the previous films, decide to retell the legend from the very beginning, and end the story without tying up all the loose threads. In other words, this must have been intended as the start of a new franchise, one that never quite got off the ground as Hammer ran into some late-60’s troubles finding American partners to co-finance and distribute their films. Challenge is a deliberate throwback to the matinee adventure movies of decades past, and probably not the kind of film the studio should have been making by 1967, but one thing is for certain: everyone’s in their comfort zone, and the film works more or less as it’s intended. Fisher had something of a revisionist take on the Hood legend, with style and a bit of grimness at the edges, but Pennington-Richards reaches all the way back to Errol Flynn, if not Douglas Fairbanks. (On a Hammer budget, of course.)

Barrie Ingham as Robin de Courtenay, soon to be Robin Hood.

There’s some nice misdirection in the opening scene. A royal deer is shot by a hunter, and in retribution the hunter is slain by a Norman lord. The grieving son fires an arrow which plants itself in the tree next to the murderous nobleman – so you’d be forgiven if you assume the boy grows up to be Robin Hood. He’s actually Stephen Fitzwarren (John Gugolka), the young brother of Lady Marian Fitzwarren (Gay Hamilton), who’s en route to stay at the castle of the de Courtenays, led by the ailing Sir John de Courtenay (William Squire). The castle is a stew of treachery fit for a Shakespearean tragedy. When de Courtenay dies, the evil Roger de Courtenay (Peter Blythe, Frankenstein Created Woman) burns the will before the astonished eyes of his family and servants, declaring himself the rightful ruler. Later that night he frames his chief rival, Robin de Courtenay (Barrie Ingham, Dr. Who and the Daleks), for the murder of another cousin. Amidst this bloody power grab, Robin flees with a friar named Tuck (James Hayter, Oliver!), and the two become wanted men. The only thing left for Robin to do is join up with the resistance – some men who are merry – and become an outlaw named Hood. First on the agenda: rescue his friend Will Scarlett (Douglas Mitchell) from hanging, and nab some green-colored garments at the market.

Gay Hamilton as Maid Marian.

Hamilton is this installment’s Maid Marian – the handmaid, for she’s disguised herself while allowing another girl to play her role as a noblewoman; she’s lovely, and gets a nice moment where she slaps the Sheriff of Nottingham (John Arnatt) twice in the face after he leers at her. Ingham at first doesn’t seem a natural fit for Robin Hood – but he grows on you as the film progresses (largely thanks to his enthusiasm), and the remaining cast members, though less impressive at a glance than that of the previous Hammer foray into Sherwood Forest, soon inhabit their roles appropriately. The key reason A Challenge for Robin Hood works is not Pennington-Richards – though he stages the action scenes with suitable excitement – but the screenplay by Bryan, which demonstrates the eternal advantage of strong storytelling. I was taken out of the familiar Hammer frame and back to the rich world of author and illustrator Howard Pyle (who authored one of the most influential interpretations of the character). Twentieth Century Fox distributed Challenge, but soon Hammer would have to tighten their belts – and the smaller budgets would reflect on the product. This, their last adventure with Robin Hood, can be linked to Terence Fisher’s The Devil Rides Out (1968) as a last hurrah for the studio at its classiest.