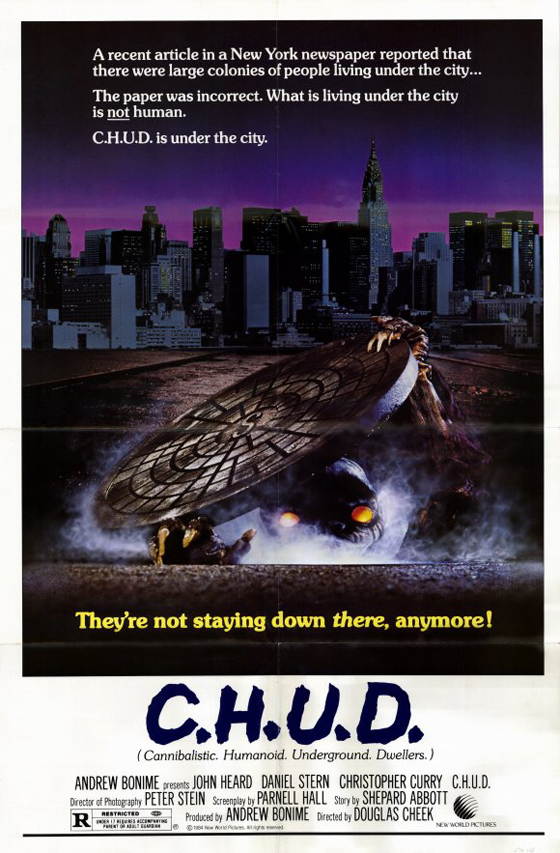

In 1984, I had never seen an R-rated movie, but I could have told you what C.H.U.D. stood for. Everyone on the playground could. I had never actually sat down to watch the film; never caught it on cable growing up; never saw a minute of footage, but was familiar with the 80’s-iconic poster of a mutant peering out of a sewer, and had probably seen television commercials for it back in ’84. So recently I asked my friend, “You know C.H.U.D.?” “Doesn’t John Goodman have a cameo in that?” “Yeah, have you seen it?” “No.” I wasn’t all that surprised. Why do you need to actually see C.H.U.D. when its chief purpose is simply to exist? I can’t imagine my video-store childhood without a copy on the shelves. Now, you know what C.H.U.D. stands for (Cannibalistic Humanoid Underground Dwellers, a phrase one uses on such a frequent basis that a handy acronym had to be established). But did you know that the twist in the film – yes, a twist! – is that it actually stands for “Contamination Hazard Urban Disposal”? When this jaw-dropping fact is revealed late in the film, I really wanted a couple of extra lines to underline the melodrama, something like, “You mean it doesn’t mean Cannibalistic Humanoid Underground Dwellers?” “No, I assure you, it means Contamination Hazard Urban Disposal.” My point is that the film runs a little short.

Fashion photographer George Cooper (John Heard) and homeless-rights advocate "The Reverend" (Daniel Stern) use a Geiger counter to track the C.H.U.D.

Actually watching the film – actually spending 96 minutes with the thing – is an entirely different, and slightly disappointing, experience after so many years of expectations. I anticipated something a bit more over-the-top, more crazed, more Humanoids from the Deep (1980). In fact, if you’re at all curious about C.H.U.D., I’d recommend Humanoids instead. The films share one thing in common: they’re both about environmental contamination creating murderous mutants. One of these films is good, lowbrow fun, and the other is C.H.U.D. At least the latter has an interesting cast, including that random Goodman cameo: John Heard plays George Cooper, a fashion photographer who, for no particular reason, is really, really pissy pretty much all the time. His girlfriend, and favorite subject, is a model named Lauren and played by Kim Greist, Sam Lowry’s crush in Brazil (1985). When homeless people (and one unfortunate Westie) start disappearing, Heard investigates with the help of a homeless rights advocate named A.J. “The Reverend” Shepherd, played by City Slicker Daniel Stern. Stern, here, is grunged-up and covered in a thick layer of grime throughout the film, to the point where you can practically smell him. In what is clearly meant to be a performance akin to Richard Dreyfuss in Jaws, he cracks wise and rants passionately against the city officials who refuse to admit the existence of monsters. In this case, they’re monsters those officials created, since a covert toxic dump in New York City’s sewers is creating the cannibalistic dwellers; the vagabonds who live in and near the sewers are therefore the first victims, and the only ones who truly know what’s going on – but society won’t pay attention to the homeless. If you sense a message here, then I can confirm you’re not in a coma.

John Heard and Kim Greist in "C.H.U.D."'s "explosive" climax.

I credit director Douglas Cheek for attempting an urban thriller with social themes. C.H.U.D. has a bit in common with Larry Cohen’s God Told Me To (1976) and Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), as well as Wolfen (1981) and the London Underground thriller Raw Meat (1973), all horror films which embraced the gritty urban landscape and focused more on characters to help ground the fantastic elements. But any movie about cannibalistic humanoid underground – I apologize, I keep forgetting there’s an acronym I can use for this – really ought to deliver on murderous mutant mayhem at some point. Instead, Cheek focuses on the slowburn approach until finally the audience is liable to forget this is even a horror film. (Some directors – Ti West, for example – can pull that off. But C.H.U.D.‘s “character development” scenes are deadly dull, with little reward.) Finally there’s a moment when Kim Greist confronts a mutant in her apartment, and a nice creature effect shows the monster’s neck lengthening, its head, with those two glowing eyes, wobbling on the stalk. Greist chops (with a sword!), the neck spurting green blood, and the severed head, fallen to the ground, turns over and bites her on the ankle. A few more scenes like these scattered throughout the film would have been useful, but for the most part, the C.H.U.D. are barely present in their own movie. I’d suggest this is a good candidate for a remake, if it weren’t for the fact that all the films I’ve compared it to already exist. You may not have gotten around to watching C.H.U.D. yet, but – really – you already have.