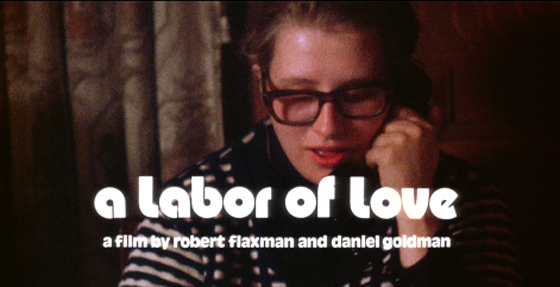

The Last Affair was intended to be a sensitive arthouse film about a young woman, Mary (Debbie Dan), whose desire for a child is thwarted by her lover’s infertility, driving her into the beds of other men. Thoughts of Truffaut and Fellini danced in the head of Iranian-born director Henri Charbakshi, but then his financiers dropped a bomb: they would only offer up the needed cash if the film contained hardcore sex scenes, to cash in on the trend of “porno chic,” even though that trend was already beginning to wane. They demanded that most of the film be nothing but X-rated sex. Charbakshi bargained his way down to 20%, because, he tells us, anything more and it might seem like porn. He was shooting during a bleak, cold winter in Chicago, and it was difficult enough to get something started in the Windy City, notoriously unfriendly to film productions in the decade following Haskell Wexler’s controversial Medium Cool (1969). His actors put on their game faces. Anything for Art. When word reached filmmakers Robert Flaxman and Daniel Goldman, they were intrigued, and asked to hang out on the set with their cameras to capture the tribulations of artistic compromise first-hand. The resulting documentary, A Labor of Love (1976), actually made it to theaters first, and received some glowing reviews. Charbakshi, who had struggled to fulfill the commitment to his financiers – problems recounted in the making-of documentary – was finally informed that he wouldn’t need to use sex scenes after all. When no one would show The Last Affair, he purchased his own Chicago theater to screen it. As Roger Ebert commented in his scathing review, “If they want wide distribution, they’ll have to buy a chain.”

I can’t comment on the qualities of The Last Affair, which toppled quickly into obscurity, though Ebert’s one-and-a-half-star review from October 13, 1976 is online. But A Labor of Love has resurfaced in the past few years, thanks to some archivists at the University of Chicago who had uncovered the second reel from the film, and enjoyed it so much that they contacted Flaxman to find a complete print. The restored, seventy-minute slice of vintage 70’s cinéma-vérité has since screened at a few film festivals, including this past weekend’s Wisconsin Film Festival, with Flaxman and associate producer John Iltis in attendance. It certainly deserves the resurrection and the raves. In this era of reality-TV oversaturation and the comedic response in mockumentary films and sitcoms (Christopher Guest’s work, The Office, etc.), A Labor of Love becomes a refreshingly unironic depiction of the inherent comedy of the human ego: specifically, that of the young amateurs and professionals who learn that making an adult film isn’t quite as easy they thought it would be. The film opens with a bearded stud – one of Charbakshi’s actors – boasting to the camera of his swinging credentials: “I love sex very much. It’s a very integral part of my existence. Very heavy sex, kinky sex, you know.” He goes on a getting-to-know-you date with his co-star, Debbie Dan, to break the ice before their sex scene. He finds her to be a stuck-up bitch. She sees him as a substance abuser afraid to reveal his true self. Debbie worries that her period is coinciding with the shooting; a female crew member heads out for a midnight feminine hygiene run. When it becomes time for the couple to do the deed under the hot lights and the cameras, Debbie complains there are too many men in the room. Flaxman’s crew leaves. Hours pass, and the actor can’t produce an erection. (I won’t spoil the solution, but it provides perhaps the biggest laugh in the film.) Debbie complains that the process is “emasculating for the man and defeminizing for the woman,” but she gamely attempts the second sex scene with another actor. They seem to have some chemistry. This just might work. It doesn’t.

Associate producer John Iltis and co-director Robert Flaxman discuss “A Labor of Love” at the 2012 Wisconsin Film Festival.

Brief explanations of The Last Affair‘s plot only add to the mounting absurdity; a significant portion of the film will take place in a brothel of male prostitutes, because it’s “every woman’s fantasy” to choose her own man. An incest fantasy sequence involving a young actress and a much older man only gets creepier when we learn that the actor wrote his own dialogue; midway through filming their oral sex scene, Charbakshi shouts in exhaustion, “Stop talking!” But there are no heroes and villains in the piece. (Okay, there’s one hero, who actually saves the day.) Debbie Dan is both sympathetic and humorously self-important. The male actors speak to Flaxman and Goldman with a mix of masculine pride and what each of them considers to be great sensitivity; but they’re hardly able to mask their anxiety at “performing” on-camera, at which point all their talk will be rendered meaningless. Charbakshi himself is the most fascinating character, both pretentious and endearing, struggling to maintain a professional atmosphere amidst the production’s human speed bumps; as he starts to unravel, he confesses that he regrets agreeing to film the sex scenes and never wants to make a hardcore film again. He continued his professional career with varied exploitation films from the women-in-prison genre (Under Lock and Key, Caged Hearts) to kiddie movies (Little Heroes, Little Heroes 2, Little Heroes 3). It seems he still needs to follow the money to get anything made at all – and the superb Labor of Love makes the chaotic role commerce plays in film production perfectly clear, even if The Last Affair was never destined to be any good in the first place.

When I was in high school, I was tasked with creating a video for U.S. History class. My friend and I treated it as though we had been commissioned to make a short film for the Oscar telecast. We collaborated upon a script which must have run to thirty or forty pages, a time travel story roughly parodying Quantum Leap, and stringing together various comedy sketches set in different points in American history. But my friend kept inserting large swaths of dialogue from his favorite movie, The Princess Bride. Our final climactic scene was nothing but the Wallace Shawn poison scene from said film. I wanted our script to be more original, but in the interests of friendship and collaboration, kept my opinion to myself. During the shooting of that scene – I should mention that every setpiece, including the Civil War battle, took place in his basement since it rained that day – I couldn’t help but notice that my friend, on-camera, started to mouth the Wallace Shawn dialogue being spoken by his fellow actor. He couldn’t help it; his lips just started moving, with a big grin on his face. That was difficult to try to edit out of the final cut; I had to settle for layering a giant black vertical bar over the portion of the screen he occupied on each occasion that he started moving his lips. I needn’t have been too concerned, because when we showed our video to the class, that scene was the most popular. Everyone recognized it, so everyone liked it. All my classmates just really, really liked The Princess Bride, and my friend’s tribute – and the reaction it received – was nothing but an unfiltered adolescent expression of that love. Such is the case of Raiders of the Lost Ark: The Adaptation (1989), only its young filmmakers took their movie love to an entirely different level.

When I was in high school, I was tasked with creating a video for U.S. History class. My friend and I treated it as though we had been commissioned to make a short film for the Oscar telecast. We collaborated upon a script which must have run to thirty or forty pages, a time travel story roughly parodying Quantum Leap, and stringing together various comedy sketches set in different points in American history. But my friend kept inserting large swaths of dialogue from his favorite movie, The Princess Bride. Our final climactic scene was nothing but the Wallace Shawn poison scene from said film. I wanted our script to be more original, but in the interests of friendship and collaboration, kept my opinion to myself. During the shooting of that scene – I should mention that every setpiece, including the Civil War battle, took place in his basement since it rained that day – I couldn’t help but notice that my friend, on-camera, started to mouth the Wallace Shawn dialogue being spoken by his fellow actor. He couldn’t help it; his lips just started moving, with a big grin on his face. That was difficult to try to edit out of the final cut; I had to settle for layering a giant black vertical bar over the portion of the screen he occupied on each occasion that he started moving his lips. I needn’t have been too concerned, because when we showed our video to the class, that scene was the most popular. Everyone recognized it, so everyone liked it. All my classmates just really, really liked The Princess Bride, and my friend’s tribute – and the reaction it received – was nothing but an unfiltered adolescent expression of that love. Such is the case of Raiders of the Lost Ark: The Adaptation (1989), only its young filmmakers took their movie love to an entirely different level.