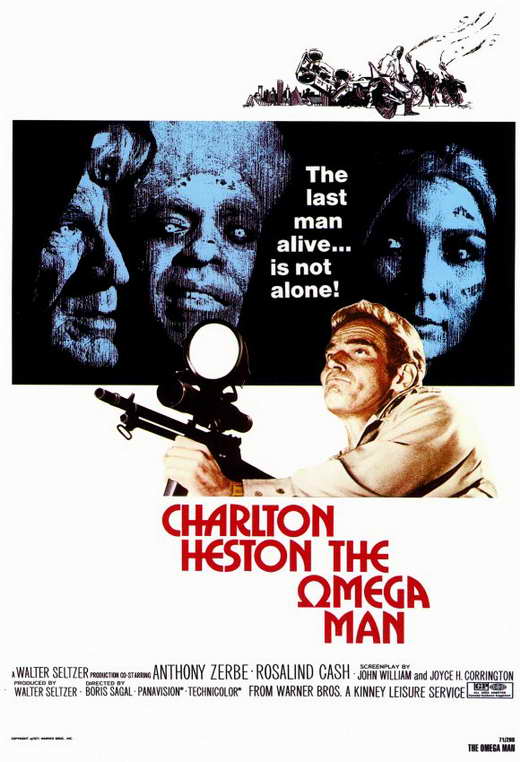

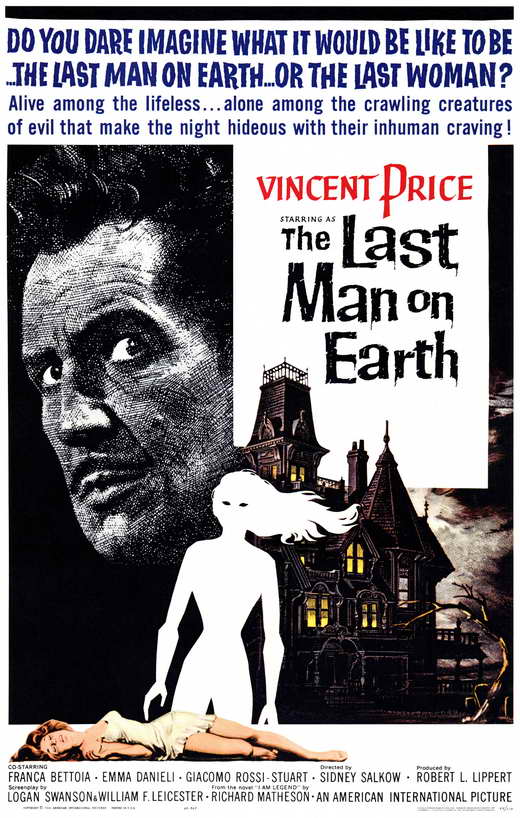

In looking at the first film adaptation of Richard Matheson’s novel I Am Legend, The Last Man on Earth (1964), I noted that the casting of Vincent Price was too much for Matheson, who had asked to be credited with a pseudonym on the screenplay. The next adaptation to come through the pipeline was a mere seven years later, and it similarly featured a left-field choice for the protagonist: Charlton Heston – the man who was Moses, El Cid, and Ben Hur. But Price, as I mentioned, rose to the material and invested himself completely in the role of a man made cynical by tragedy, struggling to survive in a world now populated by vampires out to feast on him. Heston, on the other hand, bends the film to his monumental image. The big studio (Warner Bros. in this case) production The Omega Man (1971) is very much a Chuck Heston vehicle. In the opening minutes, we see Heston speeding down empty Los Angeles streets, cruising along with a grin on his face until he notices a movement in a window. He quickly veers to the side of the road, pulls out an automatic rifle and opens fire on the fleeting shape. It’s hard to envision Vincent Price pulling that off. The Omega Man seems to belong so firmly as a piece of the actor’s filmography that the novel becomes an afterthought; indeed, the miniscule credit for Richard Matheson is preceded by “based on the novel by” without even noting its proper name. This feels like the middle chapter in a “Heston’s Choose Your Own Apocalypse” trilogy that began with Planet of the Apes (1968) and would end with Soylent Green (1973), and if it doesn’t loom quite so large as those two films in the pop culture arena – this film isn’t as quotable – it is certainly big enough that you’ve probably seen it (or at least bits of it on television). It’s one of the most influential films in the post-apocalypse genre. If The Last Man on Earth was the film that opened the door for Romero’s zombies, The Omega Man paved the way for Mad Max (1979) in how it treats a depopulated world as an action movie sandbox.

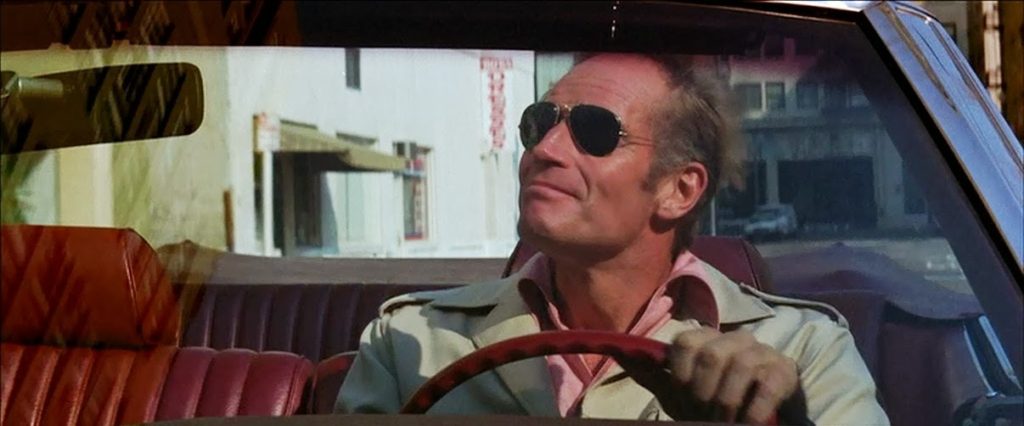

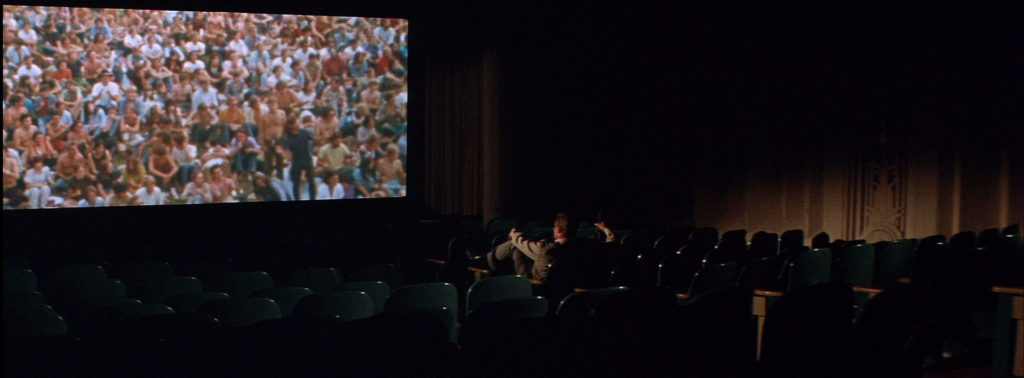

Watching “Woodstock,” held over for its third year straight.

It’s also served as a favorite of kids because it indulges in the fantasy of having the world (mostly) to yourself. Heston’s Robert Neville is a scientist who was carrying a critical vaccine when the Earth succumbed to a plague born out of germ warfare with the Soviet Union. Despite his circumstances as the last uninfected man, fighting against a cult-like group of albino mutants, he seems to be enjoying himself. When he crashes his car at the start of the film, he walks into a dealership and picks out a new one. He goes to the theater and watches Woodstock, another Warner Bros. picture, over and over again, despite the fact that one cannot imagine future NRA President Charlton Heston really enjoying Country Joe and the Fish (“Marijuana!”) and Arlo Guthrie and committing to memory, as Neville does, the documentary’s rambling interviews with young hippies. (For ironic reasons, the Woodstock scene is one of this film’s most famous.) Later, when he meets up with Lisa (Rosalind Cash), an infected human who isn’t showing symptoms, they become a couple and she enjoys outings to the department stores for a shopping spree (“Can I borrow your credit cards?”). Night of the Comet (1984), which is pretty much a satirical remake of The Omega Man, substitutes a pair of high school girls for Heston, and they brave a world of infected killers for a romp at the shopping mall; films like this give the audience space to imagine what they’d do with all the free time they want and full run of the city. Neville, however, lives modesty in his old residence: perched at the top of an L.A. apartment building, which is now in close proximity to the mutants who nightly try to murder him or burn his building down. He’s not terribly concerned, and if things seem to be getting too out of hand he simply walks out to the balcony and opens fire down at the street, annoyed at being interrupted while playing chess with a statue he calls Caesar.

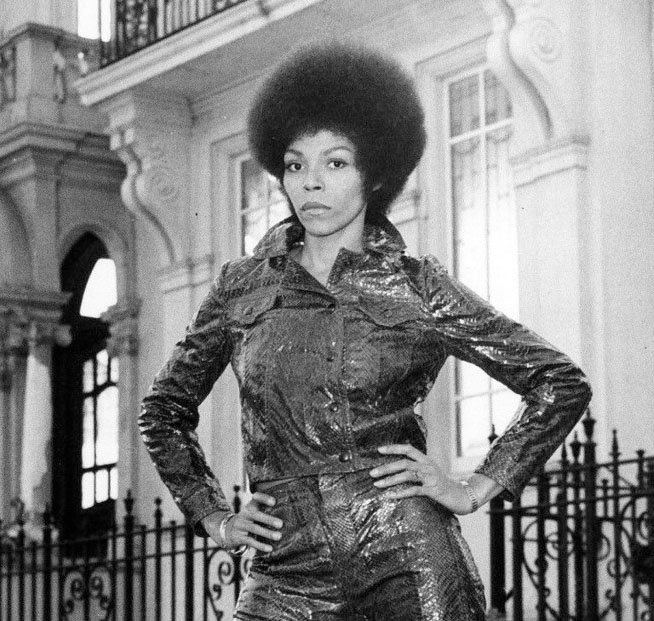

Rosalind Cash as Lisa

None of this has much to do with Matheson’s story; indeed, the film’s plot seems to be inspired solely by the book’s last couple of chapters without adapting much of anything directly. But The Omega Man has different concerns in mind. The albinos have joined together to form a group called “The Family,” an unsubtle reference to Charles Manson’s Family, led by Anthony Zerbe (Licence to Kill) as Matthias. Somewhat like those second-stage vampires that appear only at the end of Matheson’s book, this group is articulate, can use weapons, and want to kill Neville because he represents the last of an obsolete species. They also wear black hooded cloaks like devil-worshipers from a 70’s occult horror movie, though the only apparent reason for the sinister-looking clothing is to keep them out of the light. So with the Manson Family on one side, on the other we have a group of mostly asymptomatic survivors that symbolize both Youth (including a group of children and the hippie-like optimist Dutch, played by Paul Koslo) and the Black Power movement (Cash’s Lisa, looking fabulous in her early-70’s leathers). In this context, the Woodstock clip makes a bit more sense. This is a movie about generational conflict and revolution, with the unlikely figure of Charlton Heston in the middle. Indeed, it’s understandable why Neville would fall for Lisa, less so that she would fall for the middle-aged alpha male Heston, though the film tries to sell the relationship by showing Neville revealing his tender and caring side, giving a blood transfusion to restore a boy named Richie (Eric Laneuville). Regardless, the interracial romance is a welcome touch, even more so because no one makes a big deal about it. Given that director Boris Segal (Girl Happy) leans so heavily on allegory, it should be no surprise that the final image just straight-up turns Heston into Christ on the cross, with his vaccinated blood becoming the hope of future generations. (I’m surprised no one outright says, “His blood is the life.”) But look. If you’re going to make a silly, heavy-handed, symbolism-swollen genre film, you’ll have plenty of company in the early 70’s, and The Omega Man has fun with it. All its evocation of big social themes never leads to anything deep or truly revolutionary, but you do have Heston hopping around his apartment beating back albinos wearing white contact lenses, accompanied by a bombastic score by Ron Grainer, the man who wrote the theme music to Doctor Who and The Prisoner. It’s easy to criticize The Omega Man. It’s hard not to like it.