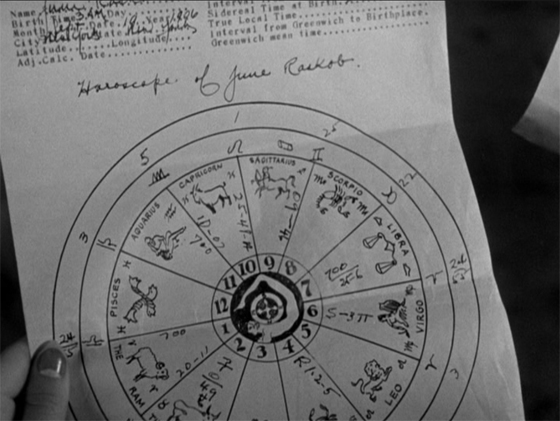

Twelve women – friends who were formerly sorority sisters – write to that great fortune-teller, the Swami Yogadachi (C. Henry Gordon), asking that he read their horoscopes. Each receives a doom-laden response. “It is ordained that someone close to you will meet death through an act of yours,” the Swami writes to June Raskob, one half of the popular circus act The Raskob Sisters. She goes to perform her acrobatic act nonetheless – and misses catching her sister, letting her plummet to her death before the eyes of the audience. June checks herself into an asylum. Then Hazel Cousins receives her horoscope from the Swami: “I see bloodshed…I see prison for you.” Shortly thereafter, she’s arrested for the murder of her husband. The Swami is distraught at the tragedies, but his beautiful, severe secretary, Ursula Georgi (Myrna Loy), is unmoved. And she seems to have dreadful powers of her own: when he looks into her eyes and predicts a terrible calamity involving a train, she gazes back and tells him he’ll suffer the same fate. Soon she’s mesmerizing him at the train station, and, in such a state, he falls backward into the tracks, right before the onrushing engine. We learn that the horoscopes of the twelve women who wrote to the Swami were actually answered by Ursula’s pen – and now she’s tracking down the remaining women to guarantee that they meet the awful ends she predicted for them, all part of an elaborate revenge scheme for a personal slight at the sorority, years ago. But she foresees trouble with the thirteenth member of the sisterhood, Laura Stanhope (Irene Dunne), who’s a rigid skeptic. “I hate her cool poise, her rigid mind!” Ursula fumes.

June Raskob receives her horoscope, which predicts her sister's tragic death.

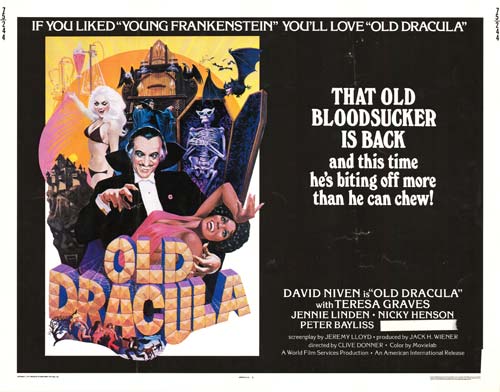

Thirteen Women (1932) is a deliriously eccentric pre-Code programmer from RKO, executive produced by David O. Selznick and helmed by RKO contract director George Archainbaud. It was adapted from a 1930 supernatural-themed bestseller by Tiffany Thayer, co-founder of the Fortean Society and a deeply eccentric fellow himself (in his later years, he claimed the atomic bomb was nothing but a hoax). The opening minutes of the film contain enough murder and mayhem for a bevy of early 30’s horrorshows, all accompanied by a stylistic visual motif – a star hurtling toward the viewer in dazzling light like the Angel of Death. These lovely young sorority sisters in their designer gowns can do nothing to stop the destructive powers of astrology. Helen Frye (Kay Johnson) claims, defiantly, “No stars are going to twinkle-twinkle me into committing suicide!” – but a few scenes later and the hypnotized girl is pointing a revolver into her own chest; Ursula, standing outside the train compartment, dons a satisfied expression when she hears the bang. Of course, this is all firmly rooted in science fact. The opening titles contain a quote from Applied Psychology: “Suggestion is a very common occurrence in the life of every normal individual…waves of certain types of crime, waves of suicide are to be explained by powers of suggestion upon certain types of mind.” And what is more suggestible than the feminine mind? (More seriously, Thirteen Women fits in neatly with a number of thrillers that elevate feminine intuition to the psychic level, such as the Shirley Jackson-derived The Haunting and, of course, Carrie.)

Laura (Irene Dunne) finds herself trapped in a runaway car when the chauffeur - Ursula's accomplice - abruptly dives out the door.

But the secret of Thirteen Women comes entirely out of left field. Ursula is of mixed race; or, as Police Sergeant Clive (Ricardo Cortez) puts it, she’s a “half-breed type: half Indian, half Japanese, I don’t know!” The real reason Ursula wants the thirteen women dead: they wouldn’t let her into their sorority because she wasn’t white. When she finally confronts Laura in the climax, she rages, “Do you know what it’s like to be a half-breed, a half-caste in a world ruled by whites? If you’re a male, you’re a ‘coolie.’ If you’re female, you’re…well… The white half of me cried for the courtesy and protection that women like you get. The only way I could free myself was by becoming white…I spent six years slaving to get money enough to put me through finishing school, to make the world accept me as white, but you – and the others – wouldn’t let me cross the color line.” One can understand her frustration: when a police bulletin is issued, it urges all officers to keep an eye out for a “half-caste Hindoo.” Myrna Loy – Nora Charles herself – is greatly miscast for such a role, but in a memorably seductive and fiery performance, she still manages to sell the idea of a woman driven to manipulation and murder when society refuses to accept her. It’s not the most sensitive treatment of the topic, to be sure, but this is a pulpy, 60-minute thriller from 1932, not an Oscar-baiting melodrama. When Ursula tries to dispatch Laura’s young son with a rubber ball stuffed with dynamite, director Archainbaud actually manages a sequence worthy of early Hitchcock: urged to not open his presents before his birthday arrives, young Bobby can’t resist the temptation, and sneaks out of bed and over to his closet, reaching up for those presents just out of reach – the box with the explosive ball teetering on the brink, just above his head. Then he manages to spill nearly all the presents but the deadly one. Flushed with guilt, he rushes back to bed – and therefore escapes death. (This is his second close call; earlier, Ursula delivered him poisoned candy.) A few more scenes like this one, and Thirteen Women would not be so obscure. As it is, it’s a sensationalistic pre-Code romp, and the new Warner Archives DVD comes highly recommended.