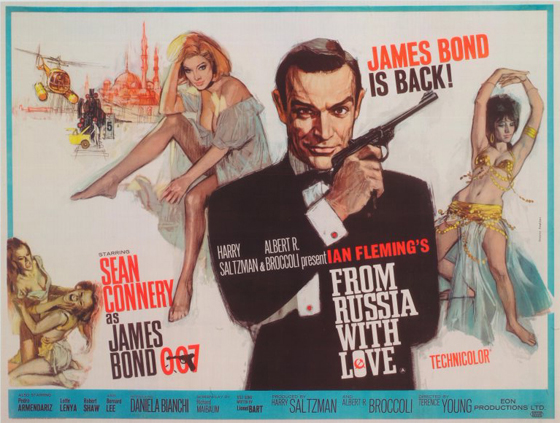

2012 marks the 50th anniversary of James Bond on film. Skyfall, the 23rd film in the “official” series initiated by Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman back in 1962 – and the third of the films to star Daniel Craig as 007 – will open later this year, around the same time that the first 22 films will be released in a 50th anniversary box set on Blu-Ray. There’s no question that James Bond has become a permanent fixture; even if the film series goes defunct entirely (a threat which seems to arise every decade or so), the character will continue to inspire video games, novels, copycats, and parodies. Ian Fleming’s agent on Her Majesty’s secret service has risen to the realm of Sherlock Holmes and Dracula: immortality through pop culture. But his beginnings were modest. Fleming, a former Reuters reporter and personal assistant to the British Director of Naval Intelligence, was insecure about his prose skills, which were admittedly awkward, particularly in the early Bond novels. He wrote Casino Royale as a lark, but when it was published in 1953 it became an overnight success, outselling its original, limited printing quickly, due in no small part to his knack for storytelling. He knew how to structure a spy yarn for maximum suspense. By the time he wrote From Russia with Love, the fifth of the books, he was confident enough that he could actually leave James Bond out of the novel entirely for nearly half its length. Famously, John F. Kennedy would later name it one of his favorite reads.

Tatiana Romanova (Daniela Bianchi) seduces 007 on the orders of SPECTRE.

Although Casino Royale had been adapted into an episode of the Climax! TV series in the 1950’s (starring Barry Nelson as “Jimmy Bond”), it wasn’t until Broccoli and Saltzman bought the rights to Doctor No, the sixth of the Bond novels, and filmed it as a big-budget action film with Sean Connery and Ursula Andress, that the character became a truly international sensation. It was a strange novel to choose to launch the series – at one point in the book, 007 wrestles with a giant squid, and he kills the villain by burying him under a pile of guano – but the producers, to great success, concentrated on the books’ most alluring attributes: sex, violence, exotic locations, and over-the-top spectacle. The Bond brand of cinema came into being fully-formed almost from the start, though it would be the second picture, From Russia with Love (1963), which solidified the formula and proved that the series would have staying-power with audiences. These pictures were blockbusters. Men enjoyed the action and the scantily-clad “Bond girls,” while the wives who accompanied them adored Connery’s Scottish brogue and laid-back masculinity. Those critics who didn’t turn up their noses at the films’ sensationalistic elements were impressed by their witty scripts and almost elegant direction – a British touch of class. It was tough to deny: whatever your complaints, they were obviously well-made movies. And From Russia with Love is one of the best of the entire series, possibly the best.

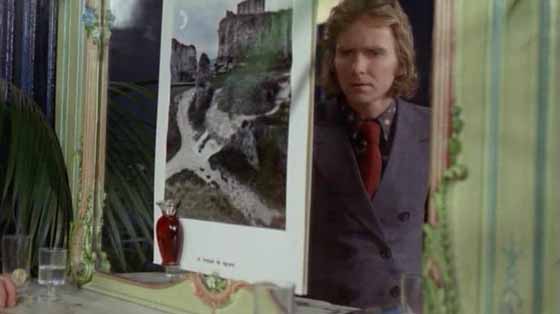

Red Grant (Robert Shaw) reveals his intentions to James Bond aboard the Orient Express.

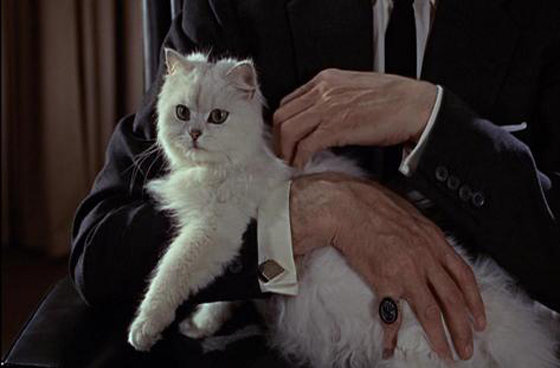

Terence Young, Dr. No‘s director, was brought back, as was Connery as 007, Bernard Lee as M, Lois Maxwell as Miss Moneypenny, and Eunice Gayson as Sylvia Trench, Bond’s main squeeze in his off-hours (though it would be her last appearance in the series). The earliest James Bond films were largely faithful to the source material, and From Russia with Love, with a script by Richard Maibaum and Johanna Harwood, only offers two key departures from Fleming. The first is understandable: our hero is not defeated by Rosa Klebb in the climactic hotel room duel (the book ends with Bond’s apparent death by Klebb’s poisoned shoe-blade, a cliffhanger ending which Fleming resolved in the opening chapters of the next installment in the series). The second, however, significantly alters the plot’s purpose. Fleming’s villains were agents of SMERSH, the real-life Russian counterintelligence agency. To make the film more apolitical, Maibaum and Harwood make the true villain the independent terrorist group SPECTRE. Although the pretty young government clerk Tatiana Romanova (Daniela Bianchi) believes she is being recruited by SMERSH to seduce a British agent and steal secrets for mother Russia, in fact she’s another pawn in SPECTRE’s game, as explicitly symbolized by the scene which follows the opening credits, a chess match won by the cerebral and sinister SPECTRE agent Kronsteen (Vladek Sheybal). SPECTRE boss Ernst Stavro Blofeld, first glimpsed in this film as two hands stroking a white cat, asks Kronsteen, ex-SMERSH director Klebb (Lotte Lenya, cabaret star and widow of composer Kurt Weill), and the cold-blooded assassin Donald “Red” Grant (Robert Shaw), to execute a plan whose ultimate goal is to steal a Russian Enigma-style encryption device and kill the British Secret Service’s top agent, James Bond. With SPECTRE, not the Soviet Union, the true puppeteers of the scheme, the plot can follow the same paces of the novel with a wrinkle that makes the narrative just a little more complex and, ultimately, more satisfying. In the novel, the encryption device is a bomb which SMERSH is attempting to smuggle into the offices of the British intelligence service; here, it’s a Hitchcock-style MacGuffin which all parties pursue, in an efficient tightening of the structure.

Anthony Dawson provides the hands, and Eric Pohlmann the voice, of Ernst Stavro Blofeld. His face (as Donald Pleasence) would not be revealed until 1967's "You Only Live Twice."

The film’s strengths are manifold. Young’s direction, abhorring close-ups (apart from a swooning shot of Tatiana’s red, parted lips), emphasizes instead the physical presence of the characters in the sets and locations, squaring off against one another: I think instantly of Bond’s introduction to Tatiana, as she lounges nude under the sheet of his bed, and he stands with a silencer-equipped pistol aimed directly at her; or Bond’s contact in Istanbul, Kerim Bey (Pedro Armendáriz), acting as gondolier as he guides 007 through the city’s subterranean canal like the Phantom of the Opera; or – the film’s most lauded scene – Red Grant confronting Bond with a gun in the cramped car of the Orient Express, Bond’s hands forced deep into his pockets, while the audience waits anxiously for the tension to be released in sudden violence. The remarkably gifted editor Peter Hunt tightened the screws further, and was even responsible for restructuring the story and reshooting certain scenes (he would later graduate to the role of Bond film director). The performances set a standard for the series, but were never again matched. Connery portrays a sardonic, emotionally reserved Bond, who only reluctantly lets Tatiana past his defenses (and even then, not by much; watch how quickly he turns on her with fierce accusations after Bey is found murdered). As in all the Connery films, much suspense is gained by watching his cool exterior crumble into something more nervous and sweat-drenched when the villain seizes an irreversible advantage. Here, it’s when Grant has a pistol pointed at his face; in the next film, it will be Goldfinger drawing a laser beam inexorably toward Bond’s genitals. Shaw makes for a terrifying villain, exuding the psychopathic qualities which were more explicitly stated in Fleming’s book. And it is impossible to imagine any other actors in the roles of Rosa Klebb and Kerim Bey than Lotte Lenya and Pedro Armendáriz, respectively.

Pedro Armendáriz as Bond's ally in Turkey, Kerim Bey.

Tragically, Armendáriz was diagnosed with terminal cancer during the film. He was eager to complete his commitments and earn the money for his family, so the shooting schedule was rearranged to accommodate all of the Kerim Bey scenes; shortly thereafter he was hospitalized, and committed suicide before the cancer could win the battle. It was a cursed production. Like something out of the script, Connery rescued his co-star Bianchi following a horrible car accident on the way to set. Director Young found himself diving underwater to rescue the pilot of a crashed helicopter during the filming of a stunt sequence gone wrong. None of this strain shows in the finished film, a classic piece of Bond cinema. There are a number of firsts for the series: the first pre-credits sequence; the first sung title theme (though Matt Munro’s vocals can’t be heard until the ending credits); the first appearance of Desmond Llewelyn as gadget-master Q; the first glimpse of Blofeld and his white cat. From Russia with Love also pushed the envelope with a brief glimpse of nudity (a dimly-lit body double for Bianchi slipping naked into bed) and many daring scenes of sexuality, including a moment when Klebb makes a lesbian pass at Tatiana. The film is rife with suggestive one-liners, but a few of them were just a little too explicit for censors, one line being very awkwardly cut from the final print: inspecting the reel of film which SPECTRE agents filmed of Bond and Tatiana in bed, Bond says, “He was right, you know – what a performance!” No matter. Fleming loved the script and was pleased with what he saw when he joined the crew at Istanbul. He died the year the film was released, but surely saw that the franchise was in good hands.