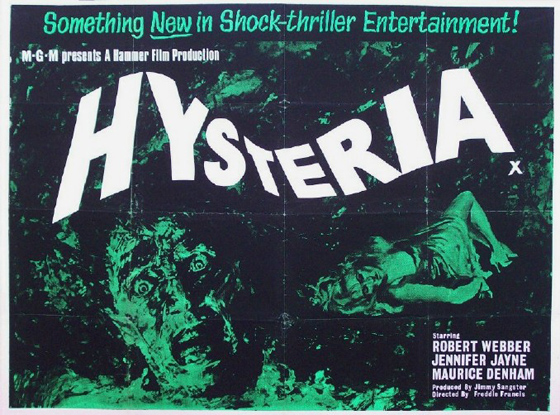

Throughout the 60’s, Hammer Films produced bucketfuls of suspense thrillers which had nothing to do with Dracula, Frankenstein, or The Mummy. The typical example would be black-and-white, overstuffed with twists, and written by Jimmy Sangster. More often than not, someone would be trying to drive someone else insane, until the victim turns the tables. Their sameness is largely due to Sangster’s love of the Henri-Georges Clouzot classic Les Diaboliques (1955), and if you saw one or two of them, you saw them all. Still, though only a few of these thrillers were truly distinguished (Scream of Fear, aka Taste of Fear, is a personal favorite), all were blessed with the horror studio’s classiness. They were perfect examples of Hammer’s ability to create a quality product on a shoestring budget. Just by glancing at the title, one would assume that Hysteria (1965) could be grouped will all those others: Maniac (1963), Paranoiac (1963), Nightmare (1964), etc. But this particular Sangster-scripted thriller is a little different, and it makes a world of difference in separating it from the pack. Clearly, the influence is less Les Diaboliques than the American film noirs of the 40’s.

X, the unknown: "Chris Smith" (Robert Webber) searches for his identity in a vacant apartment in "Hysteria."

The plot bears a certain resemblance to the great Joseph L. Mankiewicz noir Somewhere in the Night (1946); both use amnesia as the central plot device. Robert Webber (12 Angry Men) plays the man without a past, the victim of an auto accident who now calls himself “Chris Smith.” An American abroad, he stumbles through England trying to find clues to his identity, taking guidance from the doctor who treated him (Anthony Newlands), his attractive nurse (Jennifer Jayne), and an anonymous benefactor who lends him a luxury apartment in London and some spending money. Smith hires a shady private detective (Maurice Denham), and searches out the mysterious woman in a photograph he was carrying with him in the accident, the only clue to his past. The photographer informs him the woman was brutally murdered, but then Smith catches a glimpse of her in the street. His nights in the apartment become restless. He overhears a couple arguing next door, and possibly a killing; when he explores the empty rooms, he finds a running shower and a bloody knife lying on the floor, but nobody in sight. Each night he hears the same voices from the empty apartment, the same heated conversation, and begins to wonder if he’s losing his mind – a possibility raised by the private detective, who abruptly drops the case. Then the woman in the photograph (Lelia Goldoni) shows up at his door, offering to help him.

Dr. Keller (Anthony Newlands) treats the tortured Smith.

Even this late in the game, when Hammer had established a reputation of its own, it still occasionally looked to American stars to headline its films, helping secure distribution in the States. Thus the casting of Robert Webber – though this is the rare case in which this cynical strategy works in favor of the film. Unlike Brian Donlevy in the first two Quatermass films, or Macdonald Carey in These Are the Damned (1963), Webber is a perfect fit for Hysteria, and enjoyable to watch throughout. Essentially he’s a film noir archetype: the wisecracking, emotionally-guarded lone wolf that Dana Andrews and Humphrey Bogart were so good at playing in the 40’s and 50’s. (There’s a nice moment between Webber and Jayne as they study the glamor photograph: “I may have been married to her,” Webber says, deliberately cuddling in close to Jayne. “Something tells me you’re not the marrying kind,” she carefully responds.) If Chris Smith’s journey took him on a journey through London’s seamy underbelly, we might have a late-noir classic here, but Sangster does, eventually, move back to the more familiar, comfortable territory of red herrings and absurdly elaborate conspiracies that were his trademark contributions to Hammer’s suspense thrillers. Still, sharp dialogue is maintained to the very end, with appealing performances from the supporting cast, particularly Denham’s private detective, who proves to be tougher than he looks. Don Banks provides a jazzy score, and Freddie Francis directs, with his gift for drawing out every ounce of the eerie with eye-popping black-and-white photography. The film is available on DVD from the Warner Archives.