Based on Philip Loraine’s little-remembered suspense novel Day of the Arrow, J. Lee Thompson’s British thriller Eye of the Devil (1966) creeps up on its occult themes slowly, building over its hour-and-a-half toward revelations of a secret society and black magic. The cast is top-tier, headlining Deborah Kerr and David Niven, with prominent roles for Donald Pleasence, Sharon Tate (The Fearless Vampire Killers), and David Hemmings (Blow-Up). Thompson, who had directed The Guns of Navarone (1961), establishes an experimental mood in the opening scenes, offering fractured images of an arrow about to be fired into the air from a bow, a train moving through a tunnel, its somber, bearded passenger, a dove pierced by the missile and hitting the ground, a misty forest, candles, hooded figures with hidden faces, Tate’s beautiful face before a burning hearth, a fancy and well-attended dinner party, an amulet with an arcane symbol. All of these carefully chosen black-and-white images come at you rapid-fire, overwhelmingly, as if John Cassavetes had decided to boot Roman Polanski off the set and direct Rosemary’s Baby (1968) himself, in the style of Shadows (1959). Tate, of course, would soon meet and marry Polanski, and Eye of the Devil‘s plot would have been an ideal pick for the director, who loved placing the dark and mysterious in the context of the drab everyday; the story also shares elements with The Tenant (1976) and The Ninth Gate (1999). But the notion of something sinister and brutal – and often pagan – lurking just below the veneer of polite society was a natural and recurring theme for British horror: Hammer Films mined similar territory with The Witches (1966), the Dennis Wheatley adaptation of The Devil Rides Out (1968), and, most recently, Wake Wood (2011); the Warner Archives DVD of Eye of the Devil appropriately namechecks The Wicker Man (1973) in its summary.

Father Dominic (Donald Pleasence) welcomes the Marquis de Montfaucon (David Niven) back to his ancestral estate.

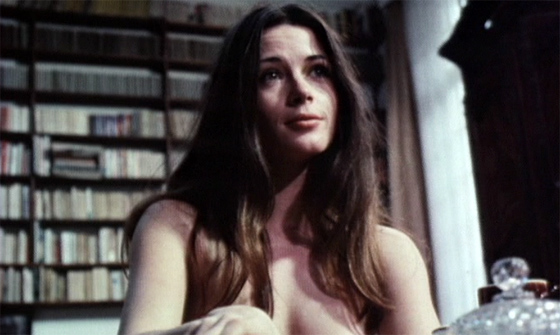

As with Rosemary’s Baby and The Witches, the film is told largely from a female point-of-view, in this case Catherine de Montfaucon (Kerr), a lady of society, whose husband Philippe (Niven), the Marquis de Montfaucon, harbors a dark secret. After Philippe receives a visitor (that somber man we glimpsed on the train), he tells his wife that he must return immediately to his ancient family’s estate; “the vineyards are failing,” he offers, as though his mere presence could restore them to health. Against his wishes, Kerr follows him, bringing with her their two children, Jacques and Antoinette. Shortly after arriving, she begins to realize she’s made a serious mistake. Philippe’s demeanor transitions from haunted to hostile and defensive. The beautiful de Caray twins who live on the estate, Odile (Tate) and Christian (Hemmings), prove to be heartless and sadistic; Christian aims an arrow directly at Catherine after she scolds him for slaying a dove right before her children. She finds more warning than sympathy from the matronly Countess Estell (Flora Robson, Black Narcissus). And as she pokes about the castle and its grounds, she glimpses mysterious rites and lurking silent figures in dark, hooded robes. Even the villagers seem to be in on the secret, casting her wicked stares. Then Odile almost gets Antoinette killed, and subsequently hypnotizes Catherine into walking to the brink of a high parapet. With this conflict now in the open, Catherine becomes hellbent on uncovering the secret of Philippe’s family, and deciphering the meaning of a painting that depicts the hooded figures circling a man in a field. Her only ally is her friend Jean-Claude (Edward Mulhare), as her husband becomes committed to the estate’s secret plot, and even her own children seem to be drawn into its influence.

Catherine (Deborah Kerr) discovers the ultimate purpose of the secret society.

Eye of the Devil looks fantastic, the black-and-white cinematography evoking an atmosphere of dread, and placing it in line with other B&W chillers of the 60’s, like The Haunting (1963), The Nanny (1965), and, of course, The Innocents (1961), which also starred Kerr. If it’s not as effective as those films, it might be because the mystery is a bit too easy to solve, and there’s not enough incident along the way to make that journey quite so memorable. Still – the sort of person who would want to seek out Eye of the Devil will find much to savor, namely in the novelty of seeing so many iconic actors assembled in a 60’s occult thriller. The de Caray twins are especially impressive, Hemmings with his bow, and Tate dressed in form-fitting black, issuing a cold smile while she asks the children to play just a bit closer to the precipice. The film seems perched between two eras of cinema, Kerr and Niven representing one, Hemmings and Tate the other – as though the battle enacted is a generational one. It also anticipates the more overtly Satanic horrors of 70’s genre cinema while maintaining the class and poise of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Ultimately it’s a curiosity, but it’s a satisfyingly well-executed one.