Here’s what they are: first frothing green spit in a petri dish, then quivering mounds of Jell-O, then pulsating green rocks, and finally, rocketing through any intermediate evolutionary stages, wobbling five-foot-tall cyclopes with waving tentacles for arms that terminate in red crab-claws lit up in Fourth of July sparklers. They eat electricity and, should those sparkler-claws touch you, you’ll be reduced to a scorched mass of human flesh. Luckily – and even though this is the first-ever human contact with an alien lifeform – the crew of the space station Gamma-3 are all outfitted with military helmets and laser guns, as if the eventuality of an alien invasion, or at least a Commie invasion, was at the forefront of the minds at NASA (this is what Newt Gingrich’s moon colony might look like). The guns seem to do precisely nothing, but that doesn’t stop the crew from firing them endlessly at the shambling Green Slimes, eventually leading to a showdown in outer space, as the men soar about in rocket packs shooting their beams at the creatures which are now fumbling about to no apparent purpose on the outer hull of the station.

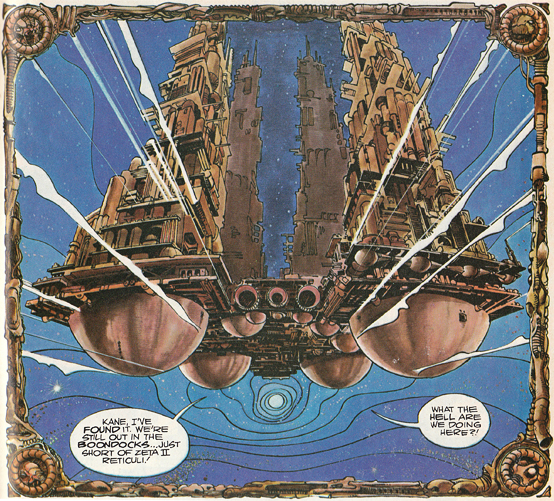

American actors trade screen time with colorful (and always unconvincing) miniatures, typical of Japanese science fiction films of the era.

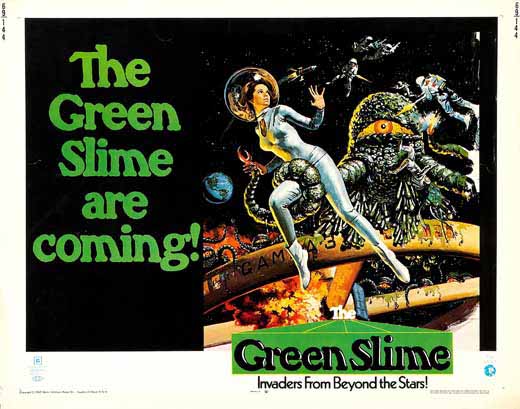

This collaboration between the U.S. and Japan was one of the more promising ventures of the Cold War; here it’s quite evident that the two former enemies could agree on one mutual love: silly monster movies. More so than the American cut/hack-job of Godzilla (1954), there’s something heartening about the pop-culture handshake between the two countries with The Green Slime (1968): it’s such a naïve, hopelessly outdated, woefully unhip piece of filmmaking that the fact that it exists at all should be reassuring. Iran might rattle their sabers at us today, but perhaps a few years from now we’ll be making The Green Slime 2 together; surely even Ahmadinejad would love to see a big-budget, CGI-led sequel. (Of course, this is only one of many American/Japanese cinematic collaborations in the decades following Hiroshima; plenty of oddities sprang forth postwar, including Sam Fuller’s very strange and kinda-great House of Bamboo.) But The Green Slime has a very unique pedigree all around. The screenplay is by journeyman writers: Tom Rowe (The Aristocats) and Charles Sinclair and William Finger (Track of the Moon Beast), working from an idea by Ivan Reiner, who was behind the equally nutty B-movies Wild, Wild Planet (1965), The War of the Planets (1966), and The Snow Devils (1967). The cast includes TV actor Robert Horton (A Man Called Shenandoah), Richard Jaeckel (The Dirty Dozen), and the sultry Italian actress Luciana Paluzzi (Thunderball‘s femme fatale). The film was shot in Japan at Toei Studios, with a Japanese director, Kinji Fukasaku, who had been making films since 1961, and in the decades following made his mark in a variety of genres, though the late director is now best known for his last film, the cult classic Battle Royale (2000). The special effects were by Akira Watanabe (Destroy All Monsters). The film begins with a pseudo-psych rock theme song by composer Charles Fox (Love, American Style). The lyrics are as follows:

Open the door you’ll find the secret

To find the answer is to keep it

You’ll believe it when you find

Something screaming ‘cross your mind

Green sliiiiiime!

What can it be, what is the reason?

Is this the end to all that breathes, and

Is it just something in your head?

Will you believe it when you’re dead?

Green sliiiiiime! Green sliiiiiime! Green sliiiiiiiiiime!

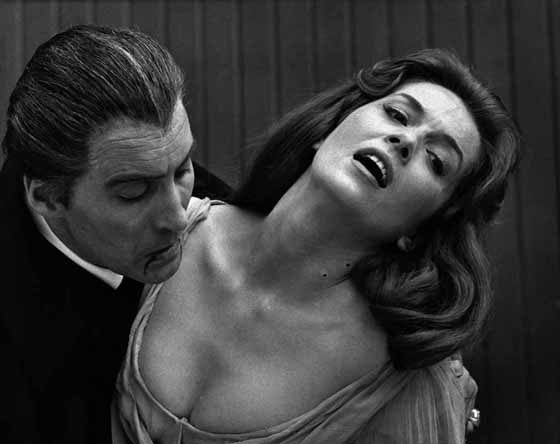

A love triangle, trimmed from the Japanese version, centers around space station commander Jack Rankin (Robert Horton), Vince Elliott (Richard Jaeckel), and Dr. Lisa Benson (Luciana Paluzzi).

The theme song abruptly ends after about forty-five seconds; the film move quickly on, as if expressing post-coital guilt. A futuristic Earth (i.e., a world covered in brightly-colored miniatures that never look like anything except little plastic toys) confronts a giant, threatening asteroid Armageddon-style: by sending out a unit to land on it and blow it to smithereens. Commander Jack Rankin (Horton) rockets out to meet space station Gamma-3, bringing with him some emotional baggage, since his ex-lover is the head of the station’s medical staff, Dr. Lisa Jansen (Paluzzi, who, despite her character’s surname, retains her thick Italian accent); but Jansen is now engaged to Vince Elliott (Jaeckel), commander of Gamma-3. The two men lock horns almost immediately, though given that they’re both the kind of bland, middle-aged louts that frequently starred in these kinds of movies from the 50’s through the 70’s, it’s a mystery what she sees in either of them. The asteroid is detonated rather efficiently, but not before a sequence in which Rankin’s team explores its orange, rocky surface, wading through shallow, ruddy pools infested with globs of a green substance. When the science officer, Halvorsen (Ted Gunther), demonstrates his find – that the substance appears to be alive, and therefore the first alien life ever discovered by mankind – Rankin angrily smashes the jar containing the entity and screams, as though the curious scientist were a five-year-old, “YOU CAN’T TAKE IT WITH YOU!”

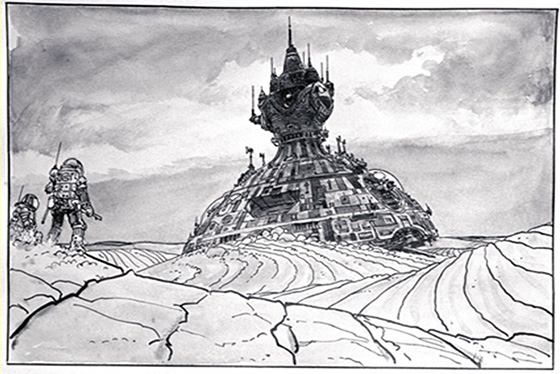

A crew from the Gamma-3 explores the asteroid that's hurtling toward Earth.

But they do take a little bit with them, for some of the substance has adhered to an explorer’s spacesuit. After the asteroid has been detonated in an explosion that can only be described as adorable, the crew settles in for some R&R on the Gamma-3. This involves some futuristic space dancing. See if you can watch this brief dialogue scene without openly gaping at the middle-aged men clumsily dancing with beautiful young fashion models in the background:

Meanwhile, the little bit of slime begins growing and multiplying. Soon enough it forms an ambulatory creature, which kills a crew member before Rankin, Elliott, and Halvorsen discover it feeding off electricity in the “main power room,” and writhing about on the ground in some kind of xenomorphic pleasure that, frankly, made me a little uncomfortable. Rankin points his giant rifle at the creature, but Halvorson pleads once more; could we at least attempt to capture a living specimen of this major scientific discovery, Commander Kill-Everything? Elliott, being leader of the Gamma-3, overrides Rankin’s orders, and some crew members run off to get “a gas gun and a net.” Although that sounds like a foolproof plan, it unfolds badly.

What follows is a solid hour of shooting lasers at the multiplying, one-eyed Green Slimes, each of them flailing their tentacles, eloctrocuting crew members randomly, and making a shrieking noise that somewhat approximates the voice of the Chicken Lady from Kids in the Hall. As it becomes increasingly clear that control of the space station is slipping inexorably into the hands (or, rather, sparklers) of the alien menace, and it’s a plague that can’t be allowed to reach the Earth, Rankin decides he’ll need to detonate the Gamma-3 and escape with the survivors in a rocket. But first, some chaos involving more laser battles and the noble self-sacrifice of Commander Elliott, over whom Dr. Jensen sheds a brief tear before inevitably surrendering herself to the elusive charms of Rankin. The Green Slime is such a strange product of its time that it’s utterly endearing. The stale script seems to have been drafted several years too late – with leftover clichés from 50’s B-movies. Apart from Paluzzi, who is always enjoyable to watch, the casting is uninspired. The juxtaposition of a (mostly) American cast with vintage 60’s Japanese effects work, including those perpetually distracting miniatures, is both jarring and delightful. (At one point, half of the space station spontaneously explodes, which is represented by showing the Gamma-3 – clearly a model hanging on a string – set on fire. Fire is difficult to film convincingly at this scale, and the resulting image is ludicrous.) The crew members wear uniforms that resemble the Lego Spacemen that I used to play with as a child, which is appropriate, since some of the miniatures look like they were constructed out of Legos. Pair it with Moon Zero Two (1969) for a double feature of deliriously out-of-touch late 60’s SF. Both are available on DVD from the Warner Archive; I can attest that The Green Slime looks spectacular, every bit the colorful kitsch that it always was.