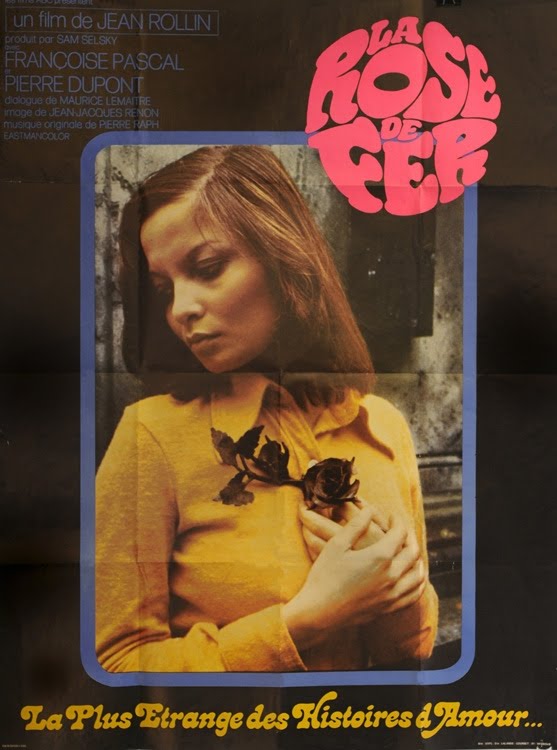

In an interview published in the Fall 1973 Cinefantastique, Jean Rollin couldn’t contain his excitement for his latest project: “It won’t be expensive; there will be none of the usual fright effects, no corpses, no blood, just one set, two actors and the night. If it works, it will be explosive.” That film would be La Rose De Fer (The Iron Rose, 1973), and it would be the purest expression yet of the Rollin universe. Two young lovers have a first date in a cemetery, crawling into a crypt to make love. When they emerge, it’s nightfall, and the cemetery has been closed. No matter how far they travel, they can’t find the gates. The graveyard becomes a labyrinth with no exit. In that same interview Rollin was still expressing satisfaction with Requiem for a Vampire (1972), in particular how he’d trimmed the dialogue to such an extent that it was a silent film for long stretches; how he had come to rely more upon images to tell his story; how the requisite sexploitation elements – so necessary to find financing – had been isolated to only a few scenes. The Iron Rose, however, was really the film that Requiem had been leading toward. Unfortunately, it also proved to be something of a dead end, commercially-speaking. His films were never welcomed by the art house crowd; they were ghettoized to the grindhouse market, playing theaters that specialized in sex films. In that respect, something as unique as The Iron Rose had nowhere to go.

Hugues Quester opens the crypt.

It is an erotic film, but not an exploitation film (a distinction many viewers and critics still have trouble making when reviewing anything with a trace of the erotic or sensual). The beautiful Françoise Pascal (Burke & Hare) plays a young woman in a very short schoolgirl’s skirt and a brightly-colored blouse that becomes half-buttoned and increasingly shredded over the course of the film – as though she were perilously traversing a “Barbarella” comic strip. In fantasy sequences, she visits the familiar Rollin beach (so prominently featured in his previous vampire cycle – it has become the world of his subconscious), standing among the sharp black rocks and gray sky, completely nude, striding through the chilly tide and obsessing over the small iron-carved rose of the title. But by Rollin standards, this is a very chaste film that would bring no satisfaction to the raincoat crowd. It was a personal project: an allegory, a fable. It’s a film about death, which lurks always at the edge of our thoughts, no matter how hard we try to push it away; Ernest Becker, author of The Denial of Death, would have embraced it. Pascal, in a mesmerizing performance, begins as an innocent, frightened of the cemetery, certainly wary of crawling into a crypt to satisfy the lusts of her impetuous new boyfriend. By the end of the film she is transformed, unwilling to leave even when the exit finally appears with the dawn. This landscape of the dead has possessed her. She’s given herself over to the allure of morbidity – the meaning behind the poem which her lover (Hugues Quester, credited as Pierre Dupont) recites at a wedding reception in the film’s opening (he recites the poem with solemnity, then gives a frivolous laugh; as my wife put it, he’s a poser).

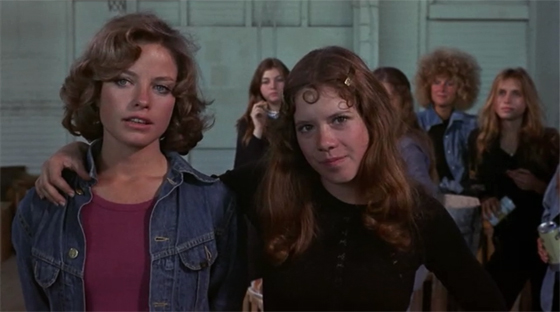

Quester and Françoise Pascal amongst the dead.

One could argue whether the film is meant to be taken as a genre horror film – she is literally possessed by the spirits of the dead – or whether this is a film about madness, as Pascal gives every sign of losing her marbles. But for Rollin, who concocted the story, I believe the real subject – and the main character – is the cemetery itself. His films recycled the same settings, just as they repeated the same themes, and sometimes the same characters; he was an obsessive fetishist. The Iron Rose gave him the opportunity to explore the world of ornate tombstones and mausoleums that was so prominent in his filmography. It allowed him to explore why this decrepit Gothic landscape should hold such fascination, but even in later films (such as, of course, Fascination) his characters remained preoccupied with death. And there was nothing he loved more than fixing his camera in close-up on a beautiful young woman’s eerily haunted stare.

Pascal possessed.

How wonderful to actually have The Iron Rose available in high definition. The new Blu-Ray release is part of a five-film launch of “The Cinema of Jean Rollin,” a reintroduction of the cult filmmaker to a wider audience (thanks to Redemption’s partnership with Kino International). To class up the films even further, they’re granted Criterion-style spine numbers…which is good, I think, because it encourages viewers to watch more than just one. I don’t think you can really appreciate Rollin until you’ve seen his style both evolve and repeat over multiple films; it becomes clearer what a unique auteur he was, whatever your ultimate opinion of his work. The Iron Rose, inevitably a visually dark film (since it takes place over the course of one night), nonetheless looks stunning, capturing the cracks on every tombstone and each pebble on the cold beach, not to mention the incongruously bright colors of the young lovers’ wardrobe. Restored from an original French-language print, it also looks very film-like, with an appropriate level of grain and some imperfections inherent in the print used – all of this appealing to anyone who’s going to sit down and watch a Jean Rollin film from the early 70’s. In other words, it’s a vast improvement over the previous DVD release; many of Redemption’s old Rollin discs were non-anamorphic, so such an upgrade is a godsend. Extras include interviews with members of the cast, the English dub track, and a strange introduction by the late Rollin. A booklet by Video Watchdog‘s esteemed Tim Lucas accompanies all the releases in the series, which include The Nude Vampire, Shiver of the Vampires, Lips of Blood, and Fascination.