There are really only two books that I keep returning to in my life: The Lord of the Rings and Dracula; while I’m content to read most books just once, these I can revisit every few years. And the movies just can’t put Dracula down, either. From F.W. Murnau’s unauthorized adaptation Nosferatu (1922) to the recent announcement by NBC that they’re developing a 19th-century-set Dracula TV series, this story has been retold so many times that it borders on unhealthy obsession. I don’t mind at all. I love the Hammer series, which brought the vampire back from the grave with each installment like a proto-Jason Voorhees, and Marvel’s Tomb of Dracula comic book, which set the Count against a team of vampire hunters descended from those who stalked him in the original novel. I love the Classics Illustrated version I read as a child, and the Bela Lugosi film, which I can happily watch with or without the Philip Glass & Kronos Quartet score. I even enjoy Guy Maddin’s fever dream filming of a Dracula ballet in Dracula: Pages from a Virgin’s Diary (2002). I think it goes back to a visit to Universal Studios when I was six years old. They had some kind of Universal Monsters show which I did not attend, because the Monster Mash pictures in the brochure intimidated me. These were monsters, after all, and there were a lot of them; and it was Dracula who seemed to be their ringmaster. He was the one Universal monster who seemed to have intelligence and cunning. To me, that was much scarier than the Frankenstein monster or the Mummy, both of whom I figured I could outwit. Still, I watched the Dracula movies because the initial fear led to a fascination; and anyway, I wasn’t allowed to watch R-rated films, so the easiest gateway into horror was the Universal canon. Lugosi, Lon Chaney, Boris Karloff, Peter Lorre, and Lon Chaney Jr. were the icons of my childhood. Abbott and Costello were the comic relief.

Lucy Seward (Kate Nelligan) and Abraham Van Helsing (Sir Laurence Olivier) in John Badham's "Dracula."

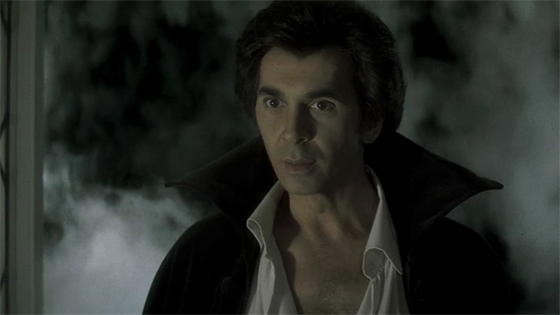

In those years of being a “monster kid” I would have watched John Badham’s 1979 adaptation of Dracula – if it weren’t rated R. (The film would probably warrant a PG-13 today.) But since I couldn’t, it eventually fell off my radar. It had settled into my consciousness as the “sexy Frank Langella version,” which I just happened to have never seen. Meanwhile I had absorbed many of the more outré variations, including Harry Nilsson playing Dracula’s son. For me, this viewing came unusually late, given that it was such a high-profile, “prestige” treatment of the material. Consider that from the late 50’s to the mid-70’s, Dracula was primarily presented through Christopher Lee’s interpretation; though he never usurped the iconic status of Lugosi’s Count, he became the fictional character’s primary ambassador. He narrated a Dracula LP (for Hammer). He starred in Jess Franco’s Count Dracula (1970) on the hopes that it would be closer to Bram Stoker’s novel; he was a vocal fan of the material and insisted that there should be a film which took the text seriously. Ironically, when that happened in 1979, he wasn’t considered for the part. The impetus for the new Universal Studios production of Dracula was a hit stage revival starring Frank Langella, so that was whom the film would showcase. (Released the same year was Love at First Bite, starring George Hamilton, a more comic but equally romantic take on the Count. Something was in the water.) Reportedly, Donald Pleasence was originally offered the role of Van Helsing, but turned it down because it was too similar to the role he’d just played in Halloween (1978); so Sir Laurence Olivier took the part, and Pleasence took on Dr. Seward. John Williams, fresh off Superman (1978), was hired as composer. Director Badham’s most recent film was a massive hit: Saturday Night Fever (1977). Clearly, this would be no Hammer movie.

The shipwreck at Whitby: an example of the film's stunning production design.

And it’s an impressive production to watch. The stormy cliffs of Whitby – where most of the action takes place – resemble those of the real-life English coastal village, with some license taken, notably the presence of Dracula’s residence, Carfax Abbey, a model designed to resemble a castle in Transylvania (in this adaptation, we never leave England). After the ship delivering the Count wrecks against the shore in the opening scenes, and the tide recedes the next day, we see it perched upon a jutting promontory, in a beautifully stylized bit of production design. Dr. Seward’s sanitarium is M.C. Escher meets Marat/Sade: a chaotic representation of the interior of a lunatic’s mind, with the occupants running free up and down stairs in all directions. Even more stylized is the interior of the abbey, which looks like a most Satanic church – or perhaps one designed by H.R. Giger. A giant carving of a bat is set into one wall, while opposite is an equally mammoth face and its gaping mouth; as with the Tod Browning version, cobwebs and critters abound. When, in that filthy, decrepit space, the handsome, cleanly-shaven Frank Langella appears, his white shirt exposing much of his chest like John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever, the incongruity is only somewhat appropriate. Maurice Binder, who created the opening credits sequences of the James Bond films from the 60’s through the 80’s, served as a visual consultant for Dracula; his touch is unmistakable when Dracula seduces Lucy Seward (Kate Nelligan). Like something out of the Moonraker (1979) credits, their love scene is depicted as an exercise in weightlessness, as their bodies are suspended, bathed in light from a foggy, blood-red tunnel. A bat flaps through. Their silhouettes are elongated, their hands becoming Nosferatu-style claws.

Maurice Binder was a visual consultant, and his touch is evident in the stylized seduction of Lucy by Dracula.

This scene is all the more striking because most of the film is deliberately shot in washed-out colors, bordering on black-and-white. (Carfax Abbey is entirely lacking in color.) The effect is that when Dracula exchanges blood with Lucy, the red-hued sequence represents an explosion of passion, like something out of a Hitchcock. The technique is used a second time in a slightly different way in the film’s climax. Badham treats the jarring arrival of daylight with a pristine blue sky, the first we’ve seen in this grimly overcast film. Color has suddenly arrived; and it’s as much color as sunlight which destroys Dracula. This visual motif echoes the underlying theme of Badham’s interpretation of the source material, one which was becoming increasingly popular: that Dracula represents a sexual threat to the Victorian repression of the residents of Whitby. Langella pays homage to Lugosi by refusing to wear fangs, but his Count also builds upon Lee’s: he’s a seducer of women. The hopelessly conservative Jonathan Harker (Trevor Eve) courts Lucy, but awkwardly; he can’t hold a candle to the devastating sexuality of this Eastern European immigrant. When Dracula is exterminated and Lucy becomes human once more, there’s a deliberate element of romantic tragedy, which has since become the de rigueur take on the vampire myth, to the extent that recent iterations, like the Twilight series, take that premise as a starting point, with all narrative and thematic contortions launched from there.

Mina Van Helsing (Jan Francis) attacks her father beneath the cemetery.

Badham’s Dracula is not a flawless film. I would suggest that it was a foolish mistake to base the script on the 1920’s stage play (by Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston) rather than returning to Stoker’s original novel. The play has been revived numerous times over the decades, and there’s an obvious marketing appeal to doing so (Lugosi was Dracula in the play first; and the 1931 film was based directly on the stage production). But a film is not the same as a play, and doesn’t need to abide by the same restrictions. Though there’s some useful expedience gained in the compression of Stoker’s large cast of characters, Deane and Balderston also make seemingly arbitrary decisions, such as reversing the parts of Mina and Lucy. (In the original novel, Mina is Jonathan’s fiancée, not Lucy.) It also seems somehow wrong to say “Mina Van Helsing.” Worse still, the decision to set exactly none of the action in Transylvania focuses the events of the film, but also removes my favorite parts of the book. There’s a dryness, too, in reducing the story to drawing-rooms and the stone halls of an asylum; the decision to drain almost all the color out of the film contributes to that dry, flavorless quality. As good as all the performances are, I would have liked to have seen Lucy and Mina more clearly as two individuals before Mina is written out. Francis Ford Coppola’s version, released over a decade later, addresses almost all these complaints – indeed, it seems primarily aimed at improving upon this particular film by ditching the play entirely and returning to, as the title says, Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Of course, Coppola and his screenwriter couldn’t help but add their own embellishments, and a new set of flaws arrived (Keanu Reeves, for example); but with the hindsight of time it’s easy to see why more viewers remember Coppola’s version than Badham’s. It’s just more fun to watch.

Dracula, touching a cross brandished by Jonathan Harker, watches it explode into flame.

But this is a respectable, occasionally striking treatment of the material, one that succeeds in its primary goal: reintroducing an iconic monster to a mainstream audience (specifically, Universal Studios reintroducing one of its Universal Monsters). Honestly, I no longer get hung up on which Dracula adaptation is more faithful. Lugosi’s is often criticized for being too stagey, but Tod Browning’s direction is unequivocally eerie. Hammer managed to squeeze in most of the elements from the novel across its series, but of course no one entry hewed all that closely to the book. Recently, the comic book adaptation The Complete Dracula boasted in advance press that it would be the first graphic novel to faithfully adapt all of Stoker’s book, which is selective amnesia, since Roy Thomas and Dick Giordano had, only a few years earlier, completed their own decades-in-the-making, text-accurate adaptation. And, dammit, that Comics Illustrated version I read as a kid was pretty faithful too. In the age of slavish literary adaptations (see: anything adapting Stieg Larsson or J.K. Rowling), I have no doubt we’ll see another version of Dracula soon that attempts to fix the errors of both John Badham and Francis Ford Coppola. But Bram Stoker’s book still exists, and it’s readily available. Our obsession is really with the Count; and we still need him, for we’d miss him as much as we would our own Id.