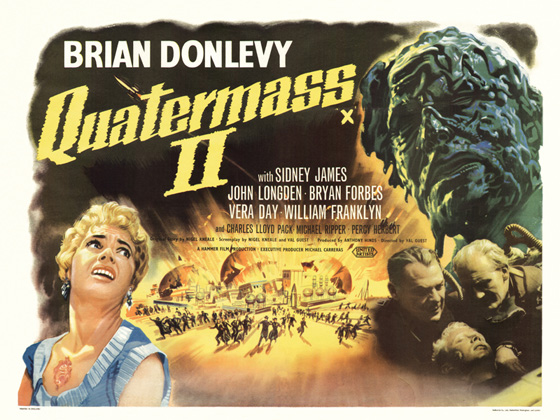

Hammer Films quickly followed up on their breakthrough success of The Quatermass Xperiment (1955; US title, The Creeping Unknown) with two films: the gory SF quickie X the Unknown (1956) – with no relation to Professor Quatermass, but just as prominent an “X” on the poster – and a proper sequel, Quatermass 2 (1957; US title, Enemy from Space), adapted from Nigel Kneale’s six-part television serial. A greater budget, thanks to co-financing from United Artists, allowed for a more ambitious science fiction thriller. While The Quatermass Xperiment was a modest but exciting variation on the Frankenstein story (with an outer space twist), Quatermass 2 – surely one of the first movie sequels to use a number to denote its place in the series – is a first-class alien invasion film. It’s just as unpredictable and intriguing as you’d expect from a script by Nigel Kneale, creator of Quatermass and author of Hammer’s superb The Abominable Snowman (1957). Despite his bitterness over the casting of American actor Brian Donlevy in the title role of the first Quatermass film (Donlevy played the character less as a scientist and more as a belligerent drill sergeant), Kneale returned to the franchise and adapted his own teleplay. Then they cast Donlevy again, to Kneale’s great frustration.

Publicity still: Professor Quatermass (Brian Donlevy) leans over the body of Broadhead (Tom Chatto), killed by an alien toxin.

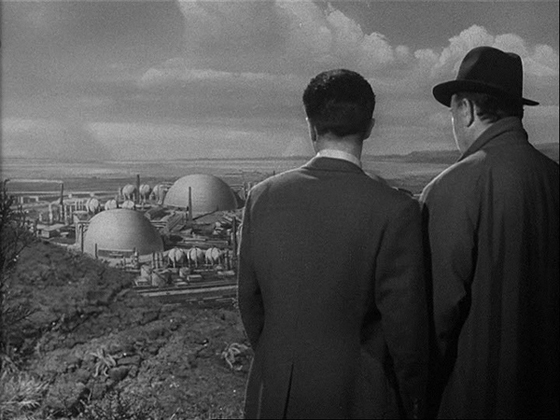

Kneale would be more pleased a decade later with Hammer’s belated Quatermass and the Pit (1967, with British actor Andrew Keir taking over the lead), but visiting Quatermass 2 for the first time on DVD, I have to say the film is an achievement, as significant to Hammer’s rising status as The Curse of Frankenstein would be the same year, though the latter film would have the greater cultural impact. Director Val Guest keeps Donlevy’s bullying approach largely in check – amusingly, the opening scene features Quatermass yelling at his research team for no good reason, then swiftly apologizing to them – with the tactic of keeping him constantly on the run from zombie-like minions and machine-gun fire. Donlevy’s emotional range is limited, clearly. But there’s so much going on here that it’s difficult to complain. The plot begins with an innocuous tediousness: Quatermass is overseeing another rocket to be launched into space, essentially picking up where the last film left off (a subtle but effective matte shot places a mammoth Atom Age rocketship just outside the professor’s window). But his radar crew keep detecting mysterious objects falling out of the sky and landing in the same general area not far from his base. He drives out into the country with one of his men and discovers a top secret military base surrounding giant domes. Happening upon one of the apparent meteorites just outside the base, the professor’s assistant immediately becomes infected upon contact, sprouting a mark like a massive boil upon his face. Then armed men in gas masks appear, seizing the infected man, and pursuing Quatermass with jeeps and gunfire. A visit to a nearby, newly-constructed town named Winnerden Flats only uncovers a small population of villagers who have been commanded to ask no questions about the military installation, and refuse to assist Quatermass in any way.

Publicity still: a village girl becomes infected by an alien intelligence spread by a meteorite.

Now, this distance into a 1950’s B-movie, we’d expect to have the whole plot mapped out (as in, what kind of animal has been affected by atomic radiation, and how big is it going to get?). But a common trait of Kneale’s Quatermass series is to keep the audience guessing; his plots are science-fiction mysteries which shapeshift from one subgenre to the next. Just as you suspect that the British government is up to something nefarious, it becomes apparent that we’re actually in the territory of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) and It Came from Outer Space (1953). A liaison for the military base – who has the mysterious boil on his wrist – claims that it’s a top-secret project for manufacturing synthetic foods, and offers to conduct a tour for Quatermass and Vincent Broadhead (Tom Chatto), an MP sympathetic to the professor’s concerns. But when the two break free of the guided tour, Broadhead falls into a vat of the “synthetic food,” an oil-like substance which burns his skin and eventually kills him; once more, Quatermass is breaking free by dodging bullets. He becomes convinced that an alien menace is infesting the Earth, and Winnerden Flats is ground zero for the invasion, traveling by meteorite from a mysterious orbiting asteroid, spreading through the populace like a virus, and commanding the construction of this base – but what’s inside those towering domes? Quatermass returns with a mob of villagers to find out.

Quatermass, infiltrating one of the domes, gazes upon the hideous thing inside.

In addition to the aforementioned matte shot of Quatermass’s rocket, there’s some superb matte work for the military base. Location shooting was performed in an oil refinery, but wide shots reveal the ominous domes, resembling a futuristic moonbase. In an eerie sequence, one of the villagers agrees to be led by the gas-masked soldiers into the dome, so he can prove its function to be harmless; as Quatermass watches through a window in the neighboring building, we see the man being led into the shadow of the great black structure, and a minute later his screams can be heard echoing through the connecting pipes. The special effects finally show their seams in the climactic sequence. I wish I could go back and carefully trim a few of the shots, because there’s a fine line between mile-high monsters of slime and two men stumbling about with blankets over their heads. Still, for late 50’s science fiction horror, this is top-drawer stuff; once the story gets going, it never lets up (surely that’s the benefit of cramming a six-part serial into 90 minutes). Hammer would quickly turn its attention to horror, and make an international name for itself; but Quatermass 2 sets the stage for a rich tradition of thoughtful British science fiction, notably those adventures of a nameless Doctor and his cosmic police box.