Ken Russell died on November 27th of this year at the age of 84. In the 60’s and the 70’s, Russell specialized in opulent, decadent spectacles; the musical biopic, in particular, was a favorite subgenre for the director, where he could rely almost solely upon visuals and music to tell his stories. And those stories were astonishing: beautiful, horrific, outlandish, both classical and cutting-edge. But by the 80’s his budgets began to shrink, and in the ensuing decades so did the opportunities. He still managed to work consistently, albeit in the realm of television and independent film. Speaking to the BBC, Glenda Jackson, who had starred in many of Russell’s films as his transgressive muse, spoke with outrage when reflecting on how the British film industry overlooked one of their greatest talents: “It was almost as if he never existed – I find it utterly scandalous for someone who was so innovative and a film director of international stature.” It does seem scandalous, when you’re watching The Music Lovers (1970). Here is someone picking up where Michael Powell left off and guiding British film into the 1970’s: it’s sophisticated filmmaking that takes risks; it rockets forward with the same “vulgar” passionate overtures of its subject, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. And like Tchaikovsky, Russell was considered just a bit too vulgar by many of his peers.

Peter Tchaikovsky (Richard Chamberlain) receives support from his sister Sasha (Sabina Maydelle).

The extraordinary opening sequence, which recalls David Lean (and, of course, Doctor Zhivago), sees Peter Tchaikovsky (Richard Chamberlain) at the height of his happiness, ecstatically charging up an icy sled run with his lover, Count Anton Chiluvsky (Christopher Gable of Russell’s Women in Love), while children in their sleds fall toward them, and eventually they both tumble happily to the bottom. On the other side of the town square, Russian soldiers parade through a crowd, and a young woman watching from a landing high above – Antonina Milyukova (Glenda Jackson) – becomes instantly infatuated with the mounted lieutenant leading their march. She races to keep up with them, sliding her hand across the railing and scattering the snow, until she finally lobs a snowball at the head of the retreating lieutenant. He turns and smiles. All this, of course, is set to the thunderous music of Tchaikovsky, which will animate the entire film. About ten minutes in, Russell indulges in a tour de force: Tchaikovsky performs “Piano Concerto 1” and Russell uses the sprawling piece to introduce all the players in our melodrama: the wealthy widow Madame von Meck (Izabella Telezynska), who, watching the composer perform, falls in love with him, and decides to sponsor his music; his sister Sasha (Sabina Maydelle), who has a sublimated incestuous longing for her brother; the Count, jealous and possessive of Peter; and Antonina, who daydreams about her whirlwind romance with that lieutenant, now her husband – and awakens to the disappointment that the chair beside her is empty. And in the center of the hall, Tchaikovsky pounds at his piano (rare for a film of this sort, the actor is clearly playing the music) – the object of all those unrequited lusts and dreams circling him. When he finishes, he receives rapturous applause…and then Nicholas Rubinstein (Max Adrian) arrives to mock his pupil’s overwrought compositions in front of those spectators who remain, instantly humiliating him. No hyperbole: this entire sequence stands as one of the strongest pieces of filmmaking of the 1970’s.

Tchaikovsky performs the First Piano Concerto.

This is still a biopic: an intensely problematic genre which has nonetheless proven irresistible to auteur directors. The best of these, as far as I’m concerned, are those which choose not to tell the entire story of someone’s life, but just one passage which can be firmly structured as good storytelling: Capote (2005), for example, which only focused on how its subject wrote In Cold Blood. Russell nearly has it both ways. The Music Lovers depicts a key moment from Tchaikovsky’s childhood, but only as a flashback, one suffered by the composer as he fails to separate the past from the present, and momentarily confuses a stranger in a bathtub with his mother being plunged into scalding water as a fatally misguided cholera treatment. The film also portrays Tchaikovsky’s death, but only as an epilogue. The story is built instead upon the composer’s struggle with his sexuality, and in particular his failed marriage to Antonina (his “Nina”). Russell shows Nina – emerging from a deeply troubled past – to be a hairsbreadth away from insanity. Peter, who responds to her rapturous love letter (in which she threatens to kill herself) with a hasty wedding, might rescue her from the brink, but his quickly withdrawn affection pushes her over it. He’s in love with the idea of being in love, much as how Nina and Madame von Meck are in the love with the idea of Tchaikovsky. His heightened, romantic feelings can’t overcome the barrier of his homosexuality. His ex-lover, the Count, constantly haunts the film, following Peter with a knowing look. His friend can’t pretend forever.

Spectators - including Peter and Nina (Glenda Jackson) - spy on two lovers with a camera obscura.

A weakness of the film is that much of this is stated outright rather than implied. Well, it was 1970. Gay cinema was still largely in the underground. When Count Anton first warns Peter against denying his past, he does so by suggestively stroking a phallic bottleneck. In one dizzying and chaotic scene, Peter and Nina get drunk during a bumpy train ride, and her attempt to seduce him is accompanied – from Peter’s point-of-view – with shots swooping through the rings in the hoop of her skirt, like falling down the rabbit-hole, albeit one that’s a bit too overburdened by Freudian meaning. Ken Russell wants us to know that Tchaikovsky is really intimidated by vaginas. When Nina undresses, she sprawls out, completely nude, on the floor of their cramped compartment, writhing like some monstrous worm – or at least this is how Peter sees her. Never has heterosexual sex been so frightening. But as much as I criticize this scene for being so obvious, I also sort of love it. It’s all so very Ken Russell. He scorned subtlety and embraced delirium. He was cinema’s Lord Byron (unsurprisingly, a character featured in one of his other films).

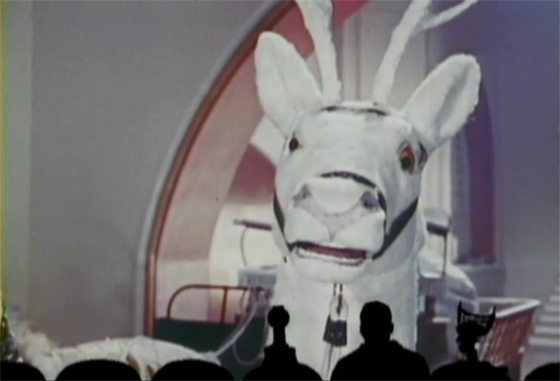

Sasha and Peter's assistant man the cannons during a scene from Ken Russell's hallucinatory treatment of the "1812 Overture."

One of the film’s most famous scenes is its climactic use of the “1812 Overture,” which is how Russell compresses the latter half of Tchaikovsky’s life. Another director might have depicted those years over the course of another hour of film – the marathon aspect of your usual biopic. Russell takes an impressionistic approach: a fantasy sequence in which Peter flees from his family and friends, to be overtaken by a mob of admirers directed by his brother Modeste (Kenneth Colley); multi-colored streamers spontaneously fall from the sky and he’s borne through a parade and draped in flowers, eventually transforming into a bronze statue. Those participants of his past that he’s so desperate to escape have their heads blown off, one by one, by firing cannons – all but Nina, who only grins madly (neglected by her husband, she’s drifted into promiscuity, and is eventually committed to a sanitorium, which Russell later depicts as a horrifying hell). We don’t need dry melodramatic scenes guiding us through every checkpoint in Tchaikovsky’s later history; we understand Russell’s telling, which is that the composer detaches himself from his sexuality, pushes past his romances and his failures, and pursues fame and glory with Modeste’s guiding hand. This is what cinema is supposed to be: visual, passionate, breathtaking. It’s shining proof that with the right subject matter, Russell was a force to be reckoned with.