In the archives of the ludicrous, a special room should be reserved for Look What’s Happened to Rosemary’s Baby (1976); a nursery, perhaps. This made-for-TV movie features exactly one returning cast member from Rosemary’s Baby (1968), Ruth Gordon as Minnie Castevet (she won an Oscar for playing the character the first time), and manages to make every wrong decision that novelist Ira Levin and filmmaker Roman Polanski had so carefully avoided almost a decade earlier. Which is to say that while it fails utterly as psychological horror, it succeeds as fabulously entertaining camp. Polanski took two hours to reveal that, yes indeed, the father of Rosemary Woodhouse’s baby is Satan. But in a trim ninety minutes (without the commercial breaks), writer/producer Anthony Wilson and director Sam O’Steen (co-editor of the 1968 film) pile in glowing demonic eyes, black magic-driven buses, electrocution, young boys getting their necks snapped, stunt car flips, mime makeup, and rock ‘n’ roll…the devil’s music.

Young Adrian/Andrew is burned by Rosemary's cross, vampire-style.

Look What’s Happened picks up right where Rosemary’s Baby left off, even playing the final dialogue from that film on the soundtrack, this time spoken by a new cast of actors (except, of course, for Gordon). Rosemary (now Patty Duke, credited as Patty Duke Astin) is raising her son with the coven from the first film, led by Roman (the great Ray Milland of The Lost Weekend and Dial “M” for Murder) and Minnie Castevet. Life in this spooky house seems to consist of wandering about in a black robe while holding a candle and chanting in Latin with the periodic refrain “Hail Satan.” The coven has named her son Adrian, but she calls him Andrew, and is secretly trying to guide him toward a life of goodness; nevertheless, his room is decorated with Satanic puppets, Nazi paraphernalia, and a giant world map just ripe for drawing big fat arrows. Her estranged husband Guy (George Maharis) – who, in the previous film, had promised their son to the coven in exchange for stardom as an actor – is now living in Hollywood, reaping the rewards of his decision. Rosemary runs away with Adrian/Andrew in tow, and takes shelter in a synagogue while Roman, Minnie, and the other witches chant their spells and shake the rafters of her shelter. She protects her son with a cross, but it burns his flesh as though he were Christopher Lee. Later, on the road and desperate, she phones up Guy and asks him to send large quantities of cash to certain locations across the United States, not telling him which she’s going to retrieve. Her distrust is well-placed, since her husband still regularly receives calls from Roman, which turn him into a nervous toady. While travelling cross-country, she has her hands full with Andrew, who at one point gets bullied by some kids and – with his eyes flashing a bright light – breaks their necks. As the first chapter of the film (“The Book of Rosemary”) concludes, she’s tricked by a deceptively friendly prostitute into boarding a bus before her child; the doors abruptly close behind her, and Andrew is once more in the hands of evil. Rosemary pounds her fists on the window and screams, but to no avail, since the bus contains neither passengers nor a driver. It barrels off toward the horizon on a highway to Hell.

Patty Duke as Rosemary Woodhouse

Chapter Two, “The Book of Adrian,” reintroduces Adrian (Stephen McHattie) in his twenties, back to his Satanic name and wearing black. But he’s not aware that he’s been raised by Satanists, and lives a relatively happy life as a singer/songwriter at the Castle Casino, run by a woman named Marjean (Tina Louise of Gilligan’s Island). His best friend, who has the very New Testament-y name of Peter Simon (David Huffman), “flunked out of divinity school” but is still prone to wearing white and keeping Adrian from picking up women at the casino. As his birthday approaches, Adrian’s “godparents,” Roman and Minnie, plot to use the occasion to test whether he’s worthy of being the Antichrist. (Guy is invited, which means he has no choice.) Adrian is to shed blood, because apparently snapping necks isn’t bloody enough; should he fail, and continue to be disappointingly not-that-evil, they will use his body as a vessel toward Satanic purposes which are left deliberately murky. “Do you know that you were conceived at midnight?” Roman casually says to Adrian over drinks at the bar. Then Roman and Minnie show their godson where the birthday party is to be held, and Adrian shows only minor concern at the eccentric touches, such as a giant sacrificial knife and a goblet of some potent elixir from which he’s urged to drink:

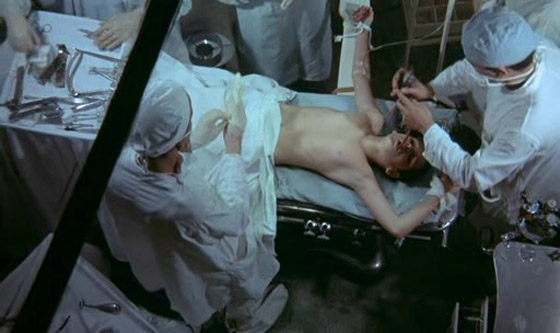

Once sufficiently drugged, Adrian is painted with white mime makeup, thus confirming the link to mimes and Satanism that you long suspected. Just as Roman, Minnie, and Guy seem to conclude that the experiment in creating an Antichrist has been a failure, and Adrian must be killed, the drugged boy stumbles out of the room and back into the club, where a band is performing a generic, lyric-free psychedelic jam while young men and women shake their sweaty bodies on the floor. Mime-Adrian stumbles about, then takes the stage to gape in awe at the audience and strike dramatic poses, giving himself over to the mediocre rock music. This, according to the theology of Look What’s Happened to Rosemary’s Baby, is the ultimate in evil. His Christian friend Peter Simon is appalled, but can only get through to Adrian when he dies (by Guy’s hand) in the most Christ-like manner short of a crown of thorns and a handful of nails. Adrian is shaken out of his stupor, but also falls into a coma, is convicted of Peter’s murder, and committed to a mental institution (while still comatose) – all during the commercial break.

Luckily, Adrian is escaping from the mental hospital within a few minutes, since he’s been able to convince the nurse, Ellen (Donna Mills, Play Misty for Me), that he’s been falsely accused of murder through a conspiracy hatched by witches. They set out to find what happened to Guy and Rosemary. Guy, meanwhile, is being informed by Roman that he needs to seek out and kill Adrian. Allow me to spoil the twist ending: Ellen is actually working for the coven; she drugs Adrian (who will drink anything) and has sex with him so that she can carry his child, who will be the true Mime Antichrist. Then Guy arrives, attempting to run over Adrian with his car, but striking Ellen instead. Adrian is taken away by the police for some reason, and, in another twist ending, Ellen survived the car crash and is now pregnant. We see the baby delivered over the ending credits. (It looks like a pretty normal baby girl. None of this “what’s wrong with his eyes?” nonsense.) So anyway, now we know what happened to Rosemary’s Baby (before Ira Levin got around to telling us his version of events, in the official sequel novel of 1997). Look What’s Happened to Rosemary’s Son’s Baby was, fortunately, never filmed.

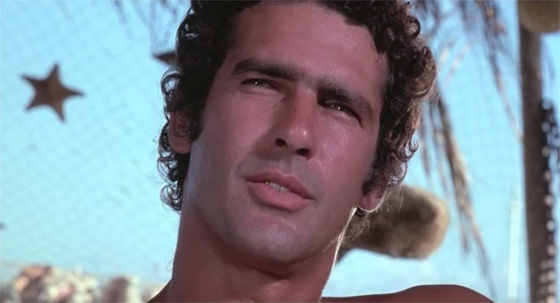

“Tin-to-re-ra. The Americans like you say, ‘tiger shark,'” helpfully explains the blond Mexican shark-hunter at the start of the film, who is leering at two girls in tight tops and bikini bottoms. But what’s actually important in this moment is the leering. Tintorera (aka Tintorera: Killer Shark, 1977) is a Mexican Jaws cash-in which almost forgets to have a killer shark in it: this is a problem. Instead, the film’s point-of-view is best expressed by our hero, Steven (Hugo Stiglitz of

“Tin-to-re-ra. The Americans like you say, ‘tiger shark,'” helpfully explains the blond Mexican shark-hunter at the start of the film, who is leering at two girls in tight tops and bikini bottoms. But what’s actually important in this moment is the leering. Tintorera (aka Tintorera: Killer Shark, 1977) is a Mexican Jaws cash-in which almost forgets to have a killer shark in it: this is a problem. Instead, the film’s point-of-view is best expressed by our hero, Steven (Hugo Stiglitz of