Before Joe Dante established a Hollywood career as the director of Piranha (1978), The Howling (1981), Gremlins (1984), Explorers (1985), and Innerspace (1987), among many others, he was a cinephile collecting 16mm footage along with his friend Jon Davison. They collaborated upon a massive montage of clips from B-movies, television shows, commercials, trailers, instructional health films, cartoons, and U.S. savings bonds propaganda; calling it The Movie Orgy (onscreen title: “Movie Orgy,” with a semi-nude woman reclining beneath the words and a cut-out head of Woody Allen popping up lewdly behind her), they took it on a Schlitz Beer-sponsored tour of colleges throughout the United States. From 1968 until sometime in the mid-70’s, Dante and Davison continued to add to the compilation’s bulk, splicing in new segments by hand, until, reportedly, The Movie Orgy expanded to about seven-and-a-half hours, a length which may actually qualify the film as a cinematic WMD. After the 70’s, the film disappeared and became the stuff of cult-film legend: just “that weird thing Joe Dante did before Hollywood Boulevard.” But in 2008 Dante revisited the project, cut it down to a slightly-more-digestible running time of close to five hours, and screened it at the New Beverly Cinema in Los Angeles (Quentin Tarantino and Edgar Wright were spotted in the crowd). More recently the Cinefamily in Los Angeles approached Dante to show the film at the found-footage “Everything Is Festival” in July of this year, and this has prompted a mini-tour, which brought the film to New York and, just this past weekend, Madison, Wisconsin. (Dante also brought the original workprint of Gremlins, and is curating the “Joe Dante Selects” series, screening some of his favorite films through November 20.) I have survived the Madison orgy and am here to tell the tale.

Joe Dante introduces "The Movie Orgy" at the Nov. 5 screening at the University of Wisconsin Cinematheque.

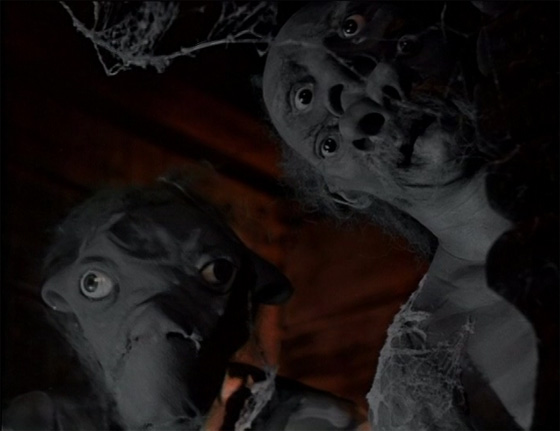

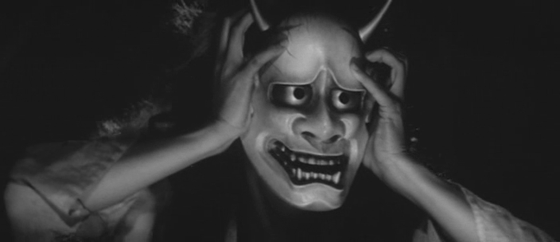

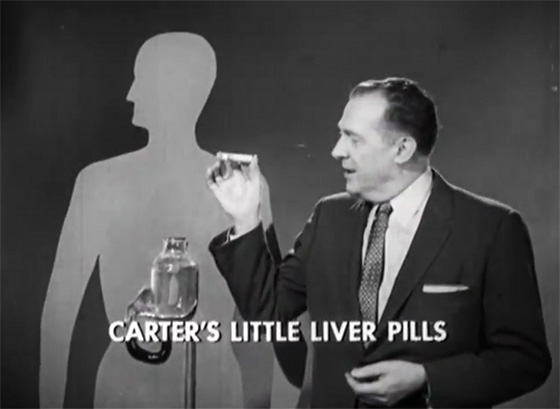

Dante introduced the film apologetically. “This is crude in every sense of the word,” he insisted, also encouraging everyone to leave and come back as they saw fit: “I won’t be offended.” When you get bored, go have a few beers and come back with a buzz, he instructed; it helps. Certainly the film was never meant to be seen in the atmosphere the UW Cinematheque provides every weekend: a colony of film buffs and students, attentive, taking notes, applauding appreciatively at the end credits of everything. One year I joined them for a 450-minute screening of Bela Tarr’s Sátántangó (1994) on one long, mesmerizing Saturday; we’re a tough bunch. But The Movie Orgy – rated “Z” (inappropriate for everyone) – was intended for a more chemically-altered, anarchic, late-60’s crowd. It’s happy to add fuel to your trips, or just play in the background while you chat with your friends. And it is crudely made – some of the gags are spoiled by the hasty splices, as the sound drops out between edits. It’s a kick anyway. Dante and Davison have crafted an expression of pure movie love, equal parts nostalgia – digging through the television shows and movies they grew up on, which weren’t as easy to revisit in the days before home video – and subversion. As a “mash-up,” no single program is shown in its entirety. They append new conclusions, or splice in characters from other films. A sudden juxtaposition – sometimes interrupting one character in mid-sentence to join another character, in another program, completing the thought – might create either an instant lowbrow gag or an anti-Vietnam statement. (A few times, clips of Richard Nixon acting asinine are interrupted by other characters saying so.) Commercials crash into the action with deliberate obnoxiousness: here’s Mighty Mouse selling you Colgate toothpaste; here’s a French commercial for a nasal spray; here are “Defenders of America” collectors cards featuring Cold War-era missiles, free with every box of Nabisco Shredded Wheat; here’s Wild Root Cream Oil hair tonic, “with lanolin and cholesterol.”

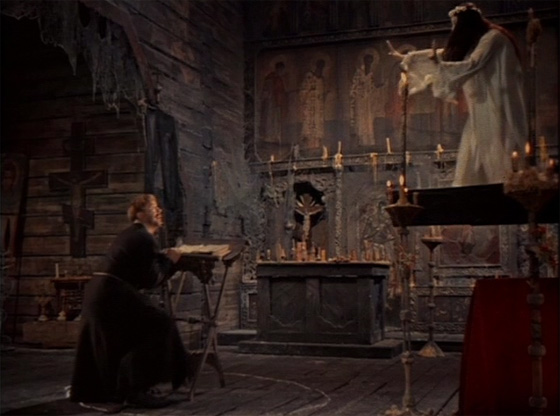

"Earth vs. the Flying Saucers" is one of the many B-movies cut-up and reconfigured for "The Movie Orgy."

There’s a stream-of-consciousness flow to the edits which reminded me of Terry Gilliam animation. When Peter Graves discusses dropping an atom bomb on Chicago to destroy a swarm of mutated locusts, we cut to an instructional film on how to handle a nearby nuclear blast; get away from the window and behind the furniture, and once the blast is over, wash your hair thoroughly to get all that radiation out. “If only the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki knew what we know today, there would have been fewer deaths.” Teenagers from Outer Space (1959) is introduced by Alfred Hitchcock, who promises scantily-clad dancing ladies at the end. (Dante and Davison then cut the film – one of the worst ever made – down to about four minutes. Hitchcock reappears and apologizes for the lack of dancing ladies.) Running gags emerge, like commercials for Bufferin, which claims to be “strong medicine for sensitive people,” those sensitive people including one man who’s demolishing a building which will leave desperate residents homeless; certainly if you find yourself in a situation where you’re putting people out of house and home, you’ll want to take some Bufferin. Kids in a classroom watch an instructional film with some nudist camp footage. A female reporter tries to take a picture of the skinny-dippers, but is told by a cop that no pictures are allowed. A program about the bravery of the modern police officer turns out to consist solely of footage of the Beast from 20,000 Fathoms picking up a cop in its jaws and swallowing him. Andy Devine presents “Andy’s Gang,” a children’s TV show in which a French waiter is berated by a talking frog puppet into confessing how he abused the Queen. Andy sings – terribly out-of-key – “Jesus Loves Me This I Know,” while a cat plays an organ and a hamster beats a marching drum, I SWEAR I SAW THIS HAPPEN.

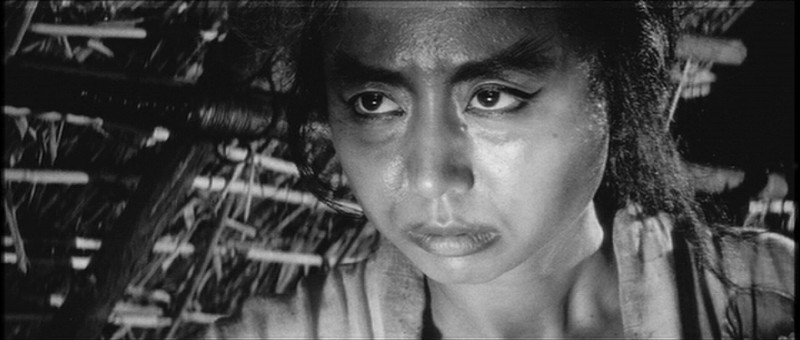

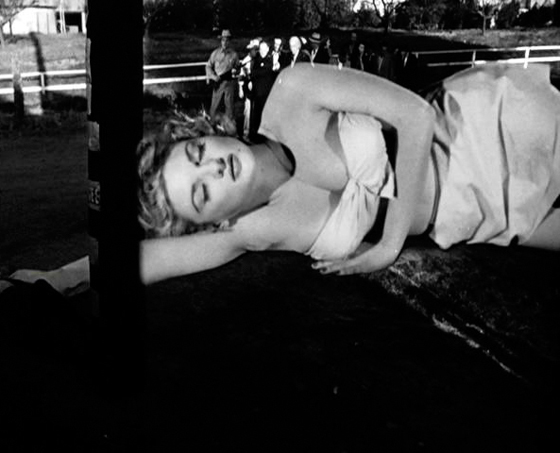

The 50 Foot Woman in defeat.

Even at such a vast running time, there is a shape and structure which gradually emerges in The Movie Orgy. A few films are begun – opening credits included – and consistently revisited throughout, until we reach their various conclusions: these include Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958), Speed Crazy (1959), Beginning of the End (1957), The Giant Gila Monster (1959), College Confidential (1960), and Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956). Tarantula (1955), The Amazing Colossal Man (1957), The Giant Claw (1957), and Duck Soup (1933) are never too far away, either. This gives the viewer something to grasp onto during this very wild ride – narratives to follow, many of which echo one another. It’s not that they run parallel; eventually, they begin to occupy the same universe. Commander Cody flies through the same sky as Superman, Sky King, and the Absent-Minded Professor’s Flubber-fueled car; he dodges the same lava flow that the caveman family is escaping in One Million B.C. (1940). The racing psychopath from Speed Crazy – whose nonstop catchphrase is “Stop crowdin’ me! Everybody’s always crowdin’ me!” – shares the same streets as Abbott and Costello, caught in a slapstick chase. You might begin to wonder why Glenn from The Amazing Colossal Man doesn’t ask the 50 Foot Woman out on a date – he’s only ten feet taller than her. No, I’m serious: after four hours you begin to ask yourself these questions. And there’s music: Dion and the Belmonts in an amazing performance of “Runaround Sue”; Elvis Presley singing “Hound Dog” to a sad-looking hound dog; the Animals (squeezed into the wrong aspect ratio, so they look like singing pencils) delivering a solemn “House of the Rising Sun”; a plumber investigating a pipe leak blames beetles, which leads to the Beatles singing “She Loves You” before a crowd of screaming girls. To say that rights issues will prevent a DVD release of this underground film is an understatement: Mickey Mouse and the Mouseketeers cameo here too. It all builds toward a very orgiastic climax, as our various films come to their destructive ends, and Roy Rogers sings “Happy Trails” to send us home. Then it’s midnight, there are still people in the theater, and the blood in our veins has congealed into wrinkled celluloid. It’s an experience, is what I’m saying.

Here’s a selection which Joe Dante’s Trailers from Hell put together to promote The Movie Orgy‘s revival, to give you a small taste: