This is a difficult one for me to approach. Don’t Look Now (1973) – as serious as it is, as complexly designed – is not a particularly difficult film. By its end, all the mysteries are solved, all the questions are answered, and it suddenly reveals itself to be quite simple. But the emotional punch is always too potent for me. I think it’s the tone. At nearly two hours, director Nicolas Roeg adapts a 55-page story by the late Daphne du Maurier with great respect and almost perfect fidelity, but he could have done the same as a one-hour episode of television. By taking his time developing the characters and lingering in the winding canals and alleys of a sinking Venice and that goddamn heavy, mournful tone, with Pino Donaggio’s delicate, beautiful score to aid him, he reduces me to dust. This film is very nearly dangerous. I love it as you would an alluring rose that keeps slicing your fingers to ribbons each time you handle it.

Donald Sutherland as John Baxter, at work in Venice.

It may pack an even greater punch for me now that I’ve been married for over a decade, and can relate more to the relationship between Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie’s grieving parents John and Laura Baxter. (If I have a child I may have to forego ever watching this again.) The film opens in Roeg’s singular collage style, depicting the drowning death of their young daughter Christine while their son helplessly watches, and they sit unaware in their living room while John reviews slides he took in Venice. Unaware, that is, until John has a strange premonition while staring at a slide of a church, and a stranger in a red hood sitting in one of the pews, the face disguised; he spills his drink and a red streak blots out the figure’s head and spreads in a stain. He runs out into the rain – a fraction too late to rescue his red raincoat-wearing daughter. Later, they’re back in Venice, sitting in a cafe. He’s returned to complete work on the restoration of a mosaic in an old church. They’re recovering from the trauma of the death, but Laura is smiling again, and finding moments of apparent happiness. He becomes disturbed that two elderly women are watching them; when Laura meets them in the bathroom, she discovers that one of the sisters, blind with milky eyes, is psychic. The woman tells Laura that Christine is with them; that she’s happy, laughing. Laura is so overwhelmed with the news that she faints when she returns to John’s table, overturning it and all the drinks. Roeg films this in slow-motion, paying strict attention to the fate of every spilled glass.

Julie Christie as Laura, meeting for psychic advice with the two sisters.

Life continues – they meet with the local bishop overseeing the church’s restoration; they wander the byways of Venice together, which are gradually becoming deserted as winter approaches and the tourist season ends. The newspapers are filled with stories of a murderer on the loose. Laura, however, can’t stop thinking about the sisters – she wants to talk to her dead daughter again. When she finally consults with them in their hotel room one late evening, the psychic warns her that danger awaits them unless they leave Venice immediately. In the middle of the night, they receive a call from England. Their son has become injured at school with a possible concussion. Laura leaves immediately, but John decides to stay for a few more days; he was work to do at the church. She flies home, but not long after, he glimpses her on a boat with the two sisters, dressed in black. Panicked that she’s returned without contacting him, he comes to believe that Laura, still emotionally fragile, has fallen under their influence, to be manipulated for some unknown purpose. He returns to the hotel where the sisters were staying, only to find it vacant. He contacts the police; he questions everyone he’s met…and catches glimpses of a small figure in a red raincoat – just like his dead Catherine – running over bridges, ducking into alleys.

John helps place a gargoyle while working on the ancient Venetian church.

Roeg had co-directed the notorious, experimental Mick Jagger film Performance (1970) with Donald Cammell, and had initiated his distinctive solo career with Walkabout (1971), a meditative film about two children who find themselves abandoned in the Australian outback. Don’t Look Now firmly established his kaleidoscopic, impressionistic style, which would serve him well in unusual films such as The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) and Bad Timing (1980). His films are like images reflected through shattered glass: there are obsessively repetitive patterns, and a narrative which constantly interrupts itself to depict moments past and forthcoming – perfect for a film about psychic premonitions, the weight of the past, and fate. A film class could fill a semester studying his editing style and use of montage in Don’t Look Now, intricate and painstakingly mapped. The most famous montage comes half-an-hour in, as we see John and Laura lying upon the bed reading a newspaper, initiating foreplay (Christie runs her fingers tenderly down Sutherland’s naked back and buttocks), making love, brushing their teeth, and getting dressed in the morning, all as a series of shots sliced into pieces and rearranged, while Donaggio’s score, both romantic and devastating, pulls you along. The disconnected images aren’t jarring, but lyrical; the effect is moving. This is a married couple reconnecting and recovering after the death of their daughter; naturally, the press at the time was more concerned with whether or not Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland had real sex on film! They didn’t. (But perhaps Roeg enjoyed all the attention, because he upped the sexual ante over his next two films.) All that tabloid chatter was a silly distraction; the scene is crucial to both the narrative and the emotional weight of the film, because they’ll have a row, and she will disappear, and John Baxter will spend the second half of the film trying to figure out just what the hell happened to his wife and why. And when brief shots from their lovemaking is intercut into the film’s very final montage, it serves to underline the story’s tragedy.

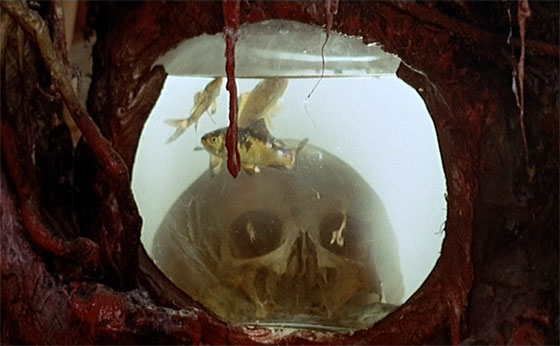

A crowd watches as a homicide victim is pulled from the canal.

The curious thing about rewatching Don’t Look Now is that it begins to seem almost unduly long. That’s perhaps because after you’ve seen it once, and its key twist has been revealed, you realize that there’s quite a lot of nothing happening in the story until you get to the end. Some of that tension toward the unknown dissipates on a reviewing, and so some narrative momentum is lost. Du Maurier, author of Rebecca and the story which inspired The Birds, composed an efficient and wry little tale, just a bit too sour to work as black comedy, but mildly shocking nonetheless (the title comes from the story’s opening line of dialogue, spoken as John points across the cafe to the two sisters staring at them). Roeg is largely faithful to the story, which was overstuffed with incident; dragging it out to this length, however, means adding some unnecessary business involving the bishop and John’s work at the church. But Roeg’s contributions shouldn’t be dismissed; in many ways he improves upon the source material. He draws stronger connections between the past and the present, placing a greater emphasis upon the mysterious little figure in the red raincoat, and lets the story stretch out and breathe. It becomes more emotional, almost unbearably so; yet he can also milk enough claustrophobic suspense from the material that it elevates Don’t Look Now to the level of a first-rate Polanski. All this means it’s no wonder that this typically makes the short lists of the best horror films of the 70’s.

I saw a snippet of Phantom of the Paradise (1974) on television as a child; I remember Paul Williams talking to the masked Phantom, and thinking, “Who is this little man with the giant glasses and the shaggy blond hair, and why is there a masked man with black lipstick and silver teeth and a bulging eyeball talking to him?” It haunted me for years…until I finally rented it about a decade ago, and said, “Aha! So this is why I’m so messed up.” Because otherwise I was watching Superfriends and The Incredible Hulk and this just did not fit in with any of my familiar paradigms. I probably did recognize Paul Williams, somewhat, because he had been in The Muppet Movie (1979), which I watched over and over, and various episodes of The Love Boat, The Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew, and Fantasy Island – all shows which were hard to avoid in the late 70’s and early 80’s. But Phantom of the Paradise represented something so far from the beaten path that it could only leave a strong mental impression. Now I own both the CD and the vinyl LP, as well as the French import DVD (because it has extras, of course, which the Region 1 version does not), and I watch it ritually every year or so. I have joined the Paradise cult, really, and yet I still cannot tell you what the hell is happening in the last five minutes of the film – and my brain is fully-formed now (more or less).

I saw a snippet of Phantom of the Paradise (1974) on television as a child; I remember Paul Williams talking to the masked Phantom, and thinking, “Who is this little man with the giant glasses and the shaggy blond hair, and why is there a masked man with black lipstick and silver teeth and a bulging eyeball talking to him?” It haunted me for years…until I finally rented it about a decade ago, and said, “Aha! So this is why I’m so messed up.” Because otherwise I was watching Superfriends and The Incredible Hulk and this just did not fit in with any of my familiar paradigms. I probably did recognize Paul Williams, somewhat, because he had been in The Muppet Movie (1979), which I watched over and over, and various episodes of The Love Boat, The Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew, and Fantasy Island – all shows which were hard to avoid in the late 70’s and early 80’s. But Phantom of the Paradise represented something so far from the beaten path that it could only leave a strong mental impression. Now I own both the CD and the vinyl LP, as well as the French import DVD (because it has extras, of course, which the Region 1 version does not), and I watch it ritually every year or so. I have joined the Paradise cult, really, and yet I still cannot tell you what the hell is happening in the last five minutes of the film – and my brain is fully-formed now (more or less).

Jean Rollin immediately followed

Jean Rollin immediately followed